Stevens, E. N., Keeports, C. R., Holmberg, N. J., Lovejoy, M. C., Pittman, L. D., Behm, A. (2012, May). Self-discrepancies and depression: Abstract reasoning skills as a moderator. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Psychological Science, Chicago, IL.

advertisement

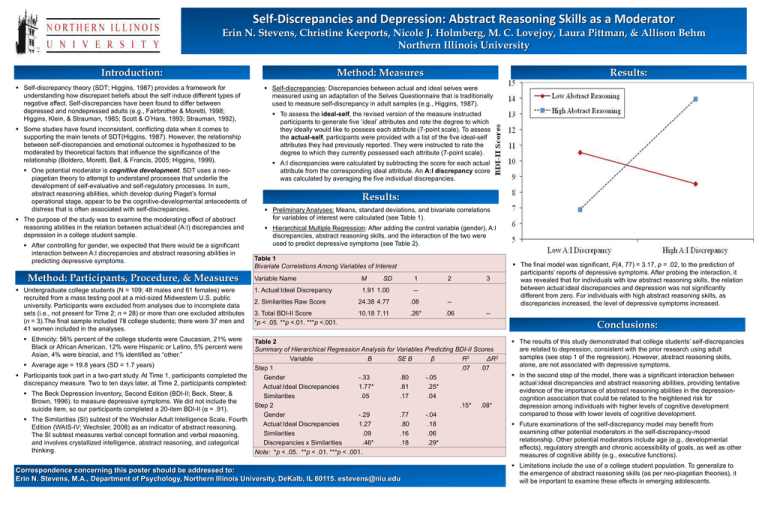

Self-Discrepancies and Depression: Abstract Reasoning Skills as a Moderator Erin N. Stevens, Christine Keeports, Nicole J. Holmberg, M. C. Lovejoy, Laura Pittman, & Allison Behm Northern Illinois University Introduction: Self-discrepancy theory (SDT; Higgins, 1987) provides a framework for understanding how discrepant beliefs about the self induce different types of negative affect. Self-discrepancies have been found to differ between depressed and nondepressed adults (e.g., Fairbrother & Moretti, 1998; Higgins, Klein, & Strauman, 1985; Scott & O’Hara, 1993; Strauman, 1992), Some studies have found inconsistent, conflicting data when it comes to supporting the main tenets of SDT(Higgins, 1987). However, the relationship between self-discrepancies and emotional outcomes is hypothesized to be moderated by theoretical factors that influence the significance of the relationship (Boldero, Moretti, Bell, & Francis, 2005; Higgins, 1999). One potential moderator is cognitive development. SDT uses a neopiagetian theory to attempt to understand processes that underlie the development of self-evaluative and self-regulatory processes. In sum, abstract reasoning abilities, which develop during Piaget’s formal operational stage, appear to be the cognitive-developmental antecedents of distress that is often associated with self-discrepancies. The purpose of the study was to examine the moderating effect of abstract reasoning abilities in the relation between actual:ideal (A:I) discrepancies and depression in a college student sample. After controlling for gender, we expected that there would be a significant interaction between A:I discrepancies and abstract reasoning abilities in predicting depressive symptoms. Method: Participants, Procedure, & Measures Undergraduate college students (N = 109; 48 males and 61 females) were recruited from a mass testing pool at a mid-sized Midwestern U.S. public university. Participants were excluded from analyses due to incomplete data sets (i.e., not present for Time 2; n = 28) or more than one excluded attributes (n = 3).The final sample included 78 college students; there were 37 men and 41 women included in the analyses. Ethnicity: 56% percent of the college students were Caucasian, 21% were Black or African American, 12% were Hispanic or Latino, 5% percent were Asian, 4% were biracial, and 1% identified as “other.” Average age = 19.8 years (SD = 1.7 years) Participants took part in a two-part study. At Time 1, participants completed the discrepancy measure. Two to ten days later, at Time 2, participants completed: The Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). to measure depressive symptoms. We did not include the suicide item, so our participants completed a 20-item BDI-II (α = .91). The Similarities (SI) subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, 2008) as an indicator of abstract reasoning. The SI subtest measures verbal concept formation and verbal reasoning, and involves crystallized intelligence, abstract reasoning, and categorical thinking. Method: Measures Results: Self-discrepancies: Discrepancies between actual and ideal selves were measured using an adaptation of the Selves Questionnaire that is traditionally used to measure self-discrepancy in adult samples (e.g., Higgins, 1987). To assess the ideal-self, the revised version of the measure instructed participants to generate five ‘ideal’ attributes and rate the degree to which they ideally would like to possess each attribute (7-point scale). To assess the actual-self, participants were provided with a list of the five ideal-self attributes they had previously reported. They were instructed to rate the degree to which they currently possessed each attribute (7-point scale). A:I discrepancies were calculated by subtracting the score for each actual attribute from the corresponding ideal attribute. An A:I discrepancy score was calculated by averaging the five individual discrepancies. Results: Preliminary Analyses: Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for variables of interest were calculated (see Table 1). Hierarchical Multiple Regression: After adding the control variable (gender), A:I discrepancies, abstract reasoning skills, and the interaction of the two were used to predict depressive symptoms (see Table 2). Table 1 Bivariate Correlations Among Variables of Interest Variable Name M SD 1 2 1. Actual:Ideal Discrepancy 1.91 1.00 -- 2. Similarities Raw Score 24.38 4.77 .08 -- 3. Total BDI-II Score *p < .05. **p <.01. ***p <.001. 10.18 7.11 .26* .06 3 -- Table 2 Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting BDI-II Scores Variable B SE B β R2 ΔR2 Step 1 .07 .07 Gender -.33 .80 -.05 Actual:Ideal Discrepancies 1.77* .81 .25* Similarities .05 .17 .04 Step 2 .15* .08* Gender -.29 .77 -.04 Actual:Ideal Discrepancies 1.27 .80 .18 Similarities .09 .16 .06 Discrepancies x Similarities .46* .18 .29* Note: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Correspondence concerning this poster should be addressed to: Erin N. Stevens, M.A., Department of Psychology, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. estevens@niu.edu The final model was significant, F(4, 77) = 3.17, p = .02, to the prediction of participants’ reports of depressive symptoms. After probing the interaction, it was revealed that for individuals with low abstract reasoning skills, the relation between actual:ideal discrepancies and depression was not significantly different from zero. For individuals with high abstract reasoning skills, as discrepancies increased, the level of depressive symptoms increased. Conclusions: The results of this study demonstrated that college students’ self-discrepancies are related to depression, consistent with the prior research using adult samples (see step 1 of the regression). However, abstract reasoning skills, alone, are not associated with depressive symptoms. In the second step of the model, there was a significant interaction between actual:ideal discrepancies and abstract reasoning abilities, providing tentative evidence of the importance of abstract reasoning abilities in the depressioncognition association that could be related to the heightened risk for depression among individuals with higher levels of cognitive development compared to those with lower levels of cognitive development. Future examinations of the self-discrepancy model may benefit from examining other potential moderators in the self-discrepancy-mood relationship. Other potential moderators include age (e.g., developmental effects), regulatory strength and chronic accessibility of goals, as well as other measures of cognitive ability (e.g., executive functions). Limitations include the use of a college student population. To generalize to the emergence of abstract reasoning skills (as per neo-piagetian theories), it will be important to examine these effects in emerging adolescents.