Redefining Principles: The Evangelical Origins of Progressivism

advertisement

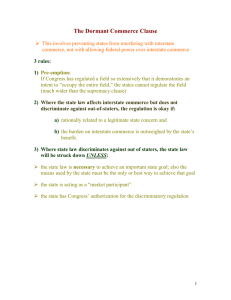

Redefining Principles: Progressivism and the New Deal Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu http://www.niu.edu/polisci/faculty/profiles/ward/ Evangelical Origins of Progressivism • The progressive critique of the Constitution in the early 20th century that led to the New Deal was presaged and to some extent made possible by earlier social movements of evangelical Christians in the 19th century who sought to ban alcohol and lotteries. • The idea that the Constitution’s practical meaning must adjust to changing social conditions is called the “living constitution” theory of constitutional interpretation. It is often associated with the progressive critique of the 1920s and 1930s. But research shows that evangelicals made similar moves decades before in order to reshape constitutional understandings and justify government power to ban alcohol and lottery sales. • When modern progressives used the living constitution theory to—among other things—allow broad government regulation of the economy and protect privacy rights involving abortion and intimate relationships, evangelicals abandoned their initial positions and instead espoused a strictconstructionist philosophy of originalism. Why? The Transformation of the Religious Sphere • America’s religious sphere was fractured during the founding era as embodied by the Constitution’s prohibition of a national church. • Yet from 1800-1830, a “Second Great Awakening”—or “Great Revival” as it is also known—took place. A wave of popular religious revival swept the nation signified by increased rates of church membership, changes in theological orthodoxy, popular movements to legally enforce Protestant mores, and cross-denominational cooperation among American Protestants. • By 1850, a majority of the nation’s religious adherents belonged to the two most evangelical sects of Protestants: Methodists and Baptists. • They spurred the progressive movements of the 19th century at both the state and national levels. The Battle Against Sinful Activities: From Slavery to Gambling and Alcohol • Late 19th century Evangelical reformers had organizational and activist roots in the pre-Civil War abolitionist movement. In 1843, for example, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison said that the Constitution’s Fugitive Slave Clause was evidence that the founding generation had entered into “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.” • Following the War, they turned their moral furor from slavery to other sinful activities and forms of property that the founding generation had tolerated, or even actively promoted. • In particular, evangelicals aimed to rid the nation of the social evils that came from lotteries and liquor consumption. • The U.S. Constitution was an obstacle to these reform movements. • As a result, evangelical moral reformers soon broke with the traditional constitutional categories that had long governed the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence respecting contracts, interstate commercial regulation, and the protection of private property rights—thus paving the way for later progressive reforms. Lotteries and the Contracts Clause • In the early 19th century, three different features of constitutional doctrine stood in the way of evangelical efforts at reform. We will discuss each of these in turn: the Contracts Clause, Due Process Clause, and Commerce Clause. • First, reformers sought to quash lotteries at the state level. Between 1830-1890 the movement steadily succeeded from zero state bans to 80% of the states. • But standing in the way were federal courts and the doctrine of vested rights, protected by the Contracts Clause, which prohibits states from “impairing the obligation of contracts.” • In a series of cases, such as Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), the Supreme Court held that the state could not impair a contract or charter that it had previously entered into. • Federal judges applied this principle to the legislative victories that evangelicals had won at the state level and struck them down. Specifically, federal courts prevented states from abolishing lotteries once legislatures had granted lottery companies corporate charters. • Eventually courts agreed that the Contracts Clause did not bar states’ attempts to ban lotteries, because state legislatures could not contract away their power to protect the health, safety and welfare of their citizens. “Alcohol, Death, and the Devil” by George Cruikshank, ca. 1830. -- Drawing shows a macabre Medusa with a skeletal head, dressed in a tunic, holding aloft a goblet of wine and exhorting a crowd of people. Behind her stands a devil who joins in the exhortation. -- Cruikshank was a popular illustrator and satirist who began campaigning against alcohol, especially gin, in the 1830s. In 1847, he renounced alcohol and became an enthusiastic supporter of the Temperance Movement in Great Britain. -- Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. The Ohio whiskey war - the ladies of Logan singing hymns in front of barrooms in aid of the temperance movement. Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, 1874 Feb. 21, p. 392. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. The Temperance Movement: Prohibition • • • • • • • The American Temperance Society (ATS) and later the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) led the movement for prohibition. Reformers sought to prohibit the sale of liquor at the state and national levels, but they faced two major obstacles. First, they faced a complex system of statutory and common law rules that had remained in operation, with only minor alterations, since the early colonial period. Second, the Due Process Clause—which prohibits states from denying life, liberty, or property without due process of law—(or its equivalent in state constitutions) allowed alcohol producers to challenge state attempts at prohibition on the ground that this would destroy their investment in business. As late as the 1820s, the granting of liquor licenses remained a relatively routine administrative mater, as it had been since the late colonial period. Beginning in the early 1830s, ATS and its allies succeeded first in persuading states to allow local governments to prohibit the granting of licenses (14 states had done so by 1847) and then to enact statewide prohibition (12 northern states by 1856). In Mugler v. Kansas (1887), the Supreme Court interpreted the Due Process Clause to allow a total ban on alcohol sales in the state of Kansas under its police power, even though this effectively destroyed the value of the owners' investments in alcohol. Ultimately, the 18th Amendment was ratified and prohibition was the law of the land from 1920-1933 until it was repealed by the 21st Amendment. • Political cartoon criticizing the alliance between the prohibition and women's suffrage movements. The genii of Prohibition emerges from a bottle labelled "intolerance". • Cartoon by Oscar Edward Cesare, published in Puck magazine, Sept. 25, 1915. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ite m/98502832/ Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Federal Action under the Commerce Clause • Reformers sought to ban the interstate shipment and sale of immoral forms of property such as alcohol and lottery tickets, but this goal threatened to transform the American federal system by allowing Congress to use the Commerce Clause for national cultural and moral reform instead of encouraging national economic activity. • The federal government was widely believed to lack the power to enact police regulations through the Commerce Clause. • Although the states did have police power, because of the Dormant Commerce Clause, it was assumed that they could not ban or tax the interstate shipment of goods moving through their borders because it was the exclusive purview of the federal government to solely regulate interstate commerce. • In the Lottery Case, Champion v. Ames (1903), the Supreme Court took a significant step toward erasing the distinction between commerce and police by allowing the federal government to completely ban the interstate shipment of lottery tickets, even though its reasons for doing so were essentially no different than police power rationales. Champion v. Ames (1903) • The case dealt with the constitutionality of the 1895 Federal Lottery Act. Congress had prohibited the movement of lottery tickets in interstate commerce, and Charles Champion was arrested for violating the act. Constitutionally, the question was whether Congress had the authority under the Commerce Clause to pass this act at all. • Writing for a divided court, Justice John Marshall Harlan I affirmed Congress’ authority to ban lottery tickets from interstate commerce, reminding his colleagues that the “the power of Congress to regulate commerce among the states is plenary, is complete in itself, and is subject to no limitations except such as may be found in the Constitution.” “We should,” Harlan warned, “hesitate before adjudging that an evil of such appalling character [as lotteries], carried on through interstate commerce, cannot be met and crushed by the only power competent to that end.” • If that is true, however – if Congress is the only power competent to meet and crush the appalling evil of lotteries – would this not lead “necessarily to the conclusion that Congress may arbitrarily exclude from commerce among the states any article, commodity, or thing, of whatever kind or nature or however useful or valuable, which it may choose, no matter with that motive, to declare it shall not be carried from one state to another”? In other words, how slippery is this slope? Harlan did not say. “It will be time enough,” he insisted, “to consider the constitutionality of such legislation when we must do so.” From Progressivism to the New Deal • • • • • • If Congress may use the Commerce Clause to combat the evil of lotteries, why may Congress not also use the Commerce Clause to combat the evil of child labor? Or liquor consumption? Or low wages, long working hours, low commodity prices, racial discrimination, marijuana possession, partial-birth abortion, or any other social or economic evil Congress desires to legislate against? During the 19th and early 20th centuries, judges sometimes tried to treat these cases narrowly as exceptions that did not alter basic constitutional principles protecting common law rights and the system of dual federalism. Eventually, however, progressives pointed to these earlier decisions about alcohol and lotteries to justify state police power to protect workers' rights, and federal power to regulate the economy generally. Thus, in his famous dissent in Lochner v. New York, Justice Holmes used "the prohibition of lotteries" to justify his argument that "state constitutions and state laws may regulate life in many ways which we as legislators might think as injudicious, or if you like as tyrannical, as this, and which, equally with this, interfere with the liberty to contract." It became increasingly difficult to distinguish these examples as special regulations of contraband; they seemed to stand for the broader authority of both federal and state governments to modify property and contract rights in the interests of public health, safety and welfare. Since 1937, of course, Congress has enacted national regulations in each of these areas under an expansive interpretation of the Commerce Clause and the Supreme Court sustained every Act until recently. The Future of Progressivism • In recent decades, the Supreme Court has scaled back the ability of congress to enact legislation under the Commerce Clause. For example, the Court ruled that the Affordable Care Act—“Obamacare”—could not be passed under this authority (although they did uphold it under the taxing power). • Will future Courts scale back commerce authority to where it was prior to 1937? • Does it matter that contemporary conservatives have abandoned the “living constitution” theory and espoused a strict-constructionist philosophy that seeks to divine the intent of the framers and the original meaning of the constitution through history and textual analysis? Bibliography • Balkin, Jack M., Living Originalism (Belknap Press, 2011). • Compton, John W., The Evangelical Origins of the Living Constitution (Harvard University Press, 2014). • Strauss, David A., The Living Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2010). • Whittington, Keith E., Constitutional Interpretation: Textual Meaning, Original Intent, and Judicial Review (University Press of Kansas, 1999).