thesis crisis

advertisement

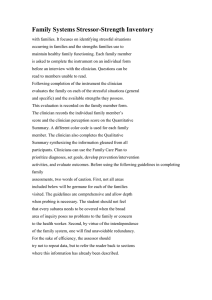

Crisis in Usual Care 0 Running head: CORRELATES OF A CRISIS IN USUAL CARE Correlates of a Crisis in Children’s Psychotherapy in Usual Care Ashley V. Robin Thesis completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Honors Program in Psychological Sciences. Under the direction of Dr. Leonard Bickman Vanderbilt University April 3, 2009 Crisis in Usual Care 1 Acknowledgements I would like to give special thanks to the following people who helped me in completing this project: my mentor, Dr. Leonard Bickman for all his guidance and support, Dr. Susan Kelley for her advice on the study design, Dr. Andrade for her statistical help, Dr. Craig Smith for giving direction in the Honors Program, and to the other committee members, Dr. David Schlundt and Steven Killingsworth. Crisis in Usual Care 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….…...4 Method………………………………………………………………………………………… 11 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………..16 Discussion……………………………………………………………………………………… 24 References……………………………………………………………………………………….28 Table 1. Implementation Schedule……………………………………………………… …….32 Table 2. Odds Ratio Results from Therapeutic Alliance Logistic Regressions…………………33 Table 3. Odds Ratio Results from Symptom and Functioning Severity Logistic Regressions ……………………………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Odds Ratio Results from Topics Logistic Regressions……………………….. ………35 Table 5. Logistic Regression Analysis of Crisis in a Session with TA and Topics Covariates ……………………………………………………………………………………….36 Table 6. Logistic Regression Analysis of Crisis in a Session with SFSS and Topics Covariates ………………………………………………………………………………...….….37 Table 7. Results from Clinician Characteristics Logistic Regression…………………...………38 Table 8. Odds Ratio Results from Client Characteristics Logistic Regressions……...…………39 Table 9. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with TA and Topics Covariates……………………………………………………………………………………… .40 Table 10. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with SFSS and Topics Covariates………………………………………………………………………………………..41 Table 11. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with a Client Characteristic as Covariate…………………………………………………………………………………………42 Table 12. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with a Clinician Characteristic as Covariate…………………………………………………………………………………………43 Table 13. Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session from Hypothetical Data of TA and Topics………………………………………………………………………….…………………44 Appendix A………………………………………………………………………………………48 Crisis in Usual Care 3 Abstract The purpose of the study was to examine crises that occur in Treatment as Usual. A children’s mental health group was examined in order to explore the correlates of a crisis session. N=7267 sessions, N=629 clients, and N=240 clinicians were included in the analysis. Logistic regressions were conducted for several factors: therapeutic alliance, symptom severity, caregiver strain, and number of topics discussed within the session. Therapeutic alliance, as rated by the clinician, and symptom severity, as rated by the clinician, both had significant associations with the occurrence of a crisis. The number of topics discussed within the session was also a significant covariate of the occurrence of a crisis. These correlates provide a basis for future studies of crises within sessions. Crisis in Usual Care 4 Introduction Research has highlighted the need for more accurate descriptions of Treatment as Usual in mental health services (Kolko, 2006; Garland, Hurlburt, Hawley, 2006; Bickman, 2008). A few studies have documented Treatment as Usual (TAU) in community settings by examining clinicians’ treatment strategies (Weersing, Weisz, & Donenberg, 2002; Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005; Bearsley-Smith, Sellick, Chesters, & Francis, 2008). Of the strategies used in TAU, therapists have most commonly reported the use of crisis management (Bearsley-Smith et. al, 2008). However, research has not identified the features of a “crisis session.” The studies reporting TAU strategies have not documented descriptions of treatment at the session level, including a session with a crisis. Without concrete descriptions of a crisis session, there has been no agreement on the definition of a crisis. This paper will attempt to identify the features of a crisis session in order to help clinicians identify and prevent crises from harming the therapeutic session. Definition of Crisis Providing adequate descriptions of sessions with crises has been overlooked in the research literature. No uniform definition of a crisis exists. For example, Bearsley-Smith and colleagues (2008) define crisis management as “immediate problem solving approaches to handle urgent or dangerous events. This might involve defusing an escalating pattern of behavior and emotions either in person or by telephone, and is typically accompanied by debriefing and follow-up.” In this definition, crisis management is a specific technique to handle an immediate, escalating problem, i.e., the crisis. Another definition describes a crisis as a brief episode of emotional distress, in which coping efforts are incapable of handling the problem (France, 2002). However, Kleespsies and Dettmer (2000) state that crises do not necessarily Crisis in Usual Care 5 imply urgency or danger but rather refer to long-lasting and non-specific problems, lasting from a few days to 6 weeks. Kleepsies and Dettmer (2000) also state a crisis is a loss of psychological equilibrium accompanied by a disruption in the individual’s baseline functioning. This definition implies a specific change in the psychological functioning of the individual as the basis for a crisis. Another definition more broadly describes crisis management as a general therapeutic framework, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and family therapy, and it encompasses specific therapeutic strategies (Baumann, Kolko, Collins, & Herschell, 2006). The preceding definitions do not complement each other and create ambiguity regarding the definition of a crisis. The broadness of these definitions could expand the crisis literature to findings about therapeutic “ruptures” in the therapeutic alliance (Safran, Crocker, McMain, & McMurry, 1990), treatment termination, changes in symptom functioning, hospitalization, suicidality, or any other potential problem within therapy. For the purpose of the current study, we have not defined crisis in any specific terms. Instead, we will use the clinicians’ reports of a crisis and then identify correlates based on their designation. Crisis Prevention Identifying the features of a crisis is important for prevention purposes. Clinicians must understand what a crisis looks like in a session before engaging in prevention. According to France (2002), secondary prevention is the optimal crisis intervention because it occurs when the client is already facing ongoing problems. Secondary prevention also occurs during the stage of a crisis when the clients are willing to change their coping mechanisms. Crises progress through three stages, but the earlier the intervention the better the client’s prognosis (France, 2002). The stages of a crisis are the impact stage, the coping stage, and the withdrawal stage. During the impact stage, an individual experiences an uncontrollable situation. Crisis in Usual Care 6 In the coping stage, individuals try to find some way of coping with the situation, either adaptive or maladaptive coping methods. If the stress continues, individuals will enter the withdrawal stage and will cease trying to resolve the problem. Preventing crises in the impact stage may combat the feelings of learned helplessness and uncontrollability associated with this stage (France, 2002). These feelings eventually lead to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideations (Seligman, 1992). Learned helplessness can even trigger a biological suicide mechanism. Preventing the crisis progression to the withdrawal stage is also important since clients more engaged in therapy have been shown to have better therapeutic outcomes than clients less engaged in therapy (McKay et. al, 2004). Also, if clients are in the withdrawal stage of a crisis, then they may attempt suicide as a cry for help or as a way of coping. Suicide attempts may occur when the crisis situation persists and their coping mechanisms have not relieved the situation (France, 2002). The faster a clinician can intervene, the better the prognosis may be for the client (Pollin, 1995). Preventing a crisis represents a legal and ethical responsibility when dealing with suicidal clients. Legally, counselors are responsible for any harm to the client caused by their negligence. Counselors must keep records showing that they have taken proper actions when dealing with a suicidal client. When a counselor’s client attempts suicide, the counselor can potentially be sued for malpractice, although proving the malpractice claims is complex. Nonetheless, the legal risks for counselors dealing with crises are still imminent (Remley, 2004). In addition to legal issues, counselors also have ethical responsibilities for their clients. According to the American Counseling Association Code of Ethics (2005) S2, counselors must limit their practice only to their areas of competence. Counselor must also seek to improve their Crisis in Usual Care 7 skills and competence. Therefore, counselors who are dealing with crises in therapy should be knowledgeable about how to deal with their clients. In order to deal with a crisis, the counselor must first identify the occurrence of a crisis. Once there are proper identification features, then clinicians can try to predict and prevent the occurrence of a crisis. Only after identification, can counselors be able to either prevent or treat a crisis. Without adequate empirical evidence about the features of a crisis, counselors cannot improve their competence in dealing with crises. Consequences of Crisis in Treatment Having competence in dealing with crises is important in combating the potential consequences in therapy. One article states the peril of having clinicians spend most of their time dealing with crisis management (Ivanov, 2007). Frequent crises may impede the long-term goals of psychotherapy. It can disrupt the therapeutic progress and can obstruct time the clinician can be using to understand the client. Time spent dealing or talking about crises cannot be spent talking about other important issues. Dealing with a crisis also deters the clinician from following usual protocols or strategies. According to an evidence-based decision-making framework, a crisis must be resolved before the treatment protocol can be delivered (Chorpita, Bernstein, & Daleiden, 2008). Crises must be resolved or prevented in order to progress through effective therapeutic strategies. Factors Related to Crises Predicting the occurrence of a crisis, such as a suicidal attempt, is not currently possible (Slaby, 1998; Jacobs, Brewer, & Klein-Benheim, 1999); however, specific factors are related to the onset of a crisis. First, precipitating events appear to precede a crisis. The precipitating Crisis in Usual Care 8 event can be a normal developmental change in one’s life, or it can be an unpredictable situation (Kleespsies & Dettmer, 2000). It can be a singular event or an accumulation of stress that causes the crisis. Second, a good therapeutic relationship is believed to help the client communicate problems that may lead toward a crisis (France, 2002). Because of therapeutic alliance’s association with therapeutic outcome (Shirk & Karver, 2003), the alliance rating may show an association with the occurrence of a crisis. Another factor that may be associated with crises is the client’s psychological functioning or symptom severity. A crisis has been defined as a change in one’s baseline level of functioning (Kleepsies & Dettmer, 2000). Although this definition describes the change in functioning as signifying the actual crisis, the change may actually occur as a precursor or consequence of the crisis. The level or a change in the level of a client’s symptoms may be associated with the occurrence a crisis. Acquiring accurate information and assessing the clients’ risk are important parts in preparing for a crisis (McAdams & Keener, 2008). This study will examine the clients’ symptom severity and whether or not the measure has an association with crises. Evidence also suggests that clinicians have their own personal styles in therapy that shape psychotherapeutic situations. Fernández-Álvarez, García, Bianco, and Santomá describe the concept of a therapist’s personal style (2003). This concept consists of the peculiarities of a therapist that lead the therapist to behave in a particular way regardless of the type of client or the client’s pathology. The study hypothesizes that the therapist’s personal style influences one’s therapeutic process and actions. The dimensions discovered in the construct of personal style include instructional, expressive, engagement, attentional, operative, and therapy assessment. Another study evaluates these dimensions of personal style in relation to the clinicians’ experience (Castaneiras, Barcia, Bianco, & Fernandez-Alvarez, 2006). Inexperienced Crisis in Usual Care 9 cognitive-oriented clinicians scored lower on the expressive dimension, reporting to be more rigid and distant compared to experienced cognitive-oriented clinicians. In addition, compared to the inexperienced psychoanalytic-oriented clinicians, the experienced psychoanalytic-oriented clinicians had lower attentional scores, reporting to have a broader focus in their sessions. These results suggest that therapists’ characteristics may influence the therapeutic outcome. Hence, we will explore the role of therapist characteristics in our study of crises. Although therapy components such as therapeutic alliance, client symptoms and functioning, and clinician experience may influence the therapeutic process, their role in crisis development must be more thoroughly examined in usual care. Current Crisis Recording in TAU Previous studies that have documented treatment strategies used in TAU have not addressed the occurrence of crises. Another limitation of these studies is their failure to document clinician actions session-by-session. Instead, therapists recall their treatment strategies on a monthly basis or after treatment termination (i.e. Schiffman, Becker, & Daleiden, 2006; Bearsley-Smith et. al, 2008). Also, since crises require immediate action, looking at the crisis within a session may be more beneficial than looking at the treatment course as a whole. Another limitation of these TAU studies has been the type of strategies that these studies have documented. Many of these studies documented techniques based upon clinical orientations (Weersing et. al, 2002; Bambery, Porcerelli, & Ablon, 2007). For example, one measure, called the Therapy Procedures Checklist requires therapists to report the techniques they used in therapy. The items on the checklist include techniques mostly from the clinical orientations of psychodynamic, cognitive, or behavioral techniques. However, up to 18% of the study’s sample ascribed to an orientation other than the previous three. Another study found that Crisis in Usual Care 10 clinicians describe their techniques as eclectic rather than ascribing to one orientation (Santa Ana, 2007). Thus, examining treatment as usual based upon clinical orientation may be an inaccurate representation of clinicians’ actual techniques. Evidence also supports the use of a common factors framework in examining psychotherapy rather than specific clinical orientations (Bickman, 2005). Hence, this study will examine the issues that therapists’ have documented within a session through a session report measure. The items on this measure do not pertain to specific clinical orientations but rather represent a common factors approach. This study will explore the topics discussed within session to determine their relationship with the occurrence of crises. Another limitation of these studies is the failure to address the occurrence of crises within TAU. One study mentions that crisis management is the most common strategy used in TAU (Bearsley-Smith et.al, 2008); however the other studies documenting TAU do not mention crises in their studies. Current Study The purpose of this study is to identify the characteristics of crises occurring within sessions in order to describe the environment of a crisis. For the purpose of this study, we will not propose any one definition for a crisis in therapy. Rather, we will use the clinician’s report of time spent dealing with a crisis within a session. Roberts and Everly (2006) propose that a crisis is not a particular dangerous event, but it is the perception of a certain situation. Using only a clinician’s perspective of a crisis situation should not diminish the importance of its existence, although the clinician’s perspective of therapeutic processes may differ from the client’s perspective. For example, in one study therapists and clients viewed videotapes of therapy sessions and subjectively identified any episode that resulted in a change in the client. Crisis in Usual Care 11 (Fiedler & Rogge, 1989). The clinicians identified more episodes than the clients did, suggesting that the clinicians found more noteworthy changes in therapy sessions. Clinicians may be more sensitive to client changes, and, thus, their reports of a crisis may differ from their clients’ report. However, using the clinicians’ reports of a crisis is appropriate for the purposes of exploring crises in TAU and providing a framework for future crisis research. Using the clinicians’ reports, we will then profile the characteristics of a “crisis” session. We will explore the following covariates’ associations with the occurrence of a crisis within a session: therapeutic alliance measures, type of topics discussed within a session, characteristics of the clinician, characteristics of the client, symptoms and functioning of the client, and caregiver strain. This information may serve two purposes. First, identifying the correlates of a crisis provides a basis for understanding the definition of a crisis. Second, this study will help identify factors that may play a role within the stages of crises. Third, this study will examine important therapeutic factors that may be overlooked in the sparse studies of TAU. Lastly, this study will address covariates within individual sessions rather than the whole treatment course. This more detailed level of analysis will be helpful in examining TAU characteristics within a session. Method The Center for Evaluation and Program Improvement (CEPI) developed the Contextualized Feedback Intervention and Training (CFIT) program (Bickman, Riemer, Breda, & Kelley, 2006). The CFIT program contains various self-scoring measures and provides online feedback to clinicians. Although we will not be examining the effects of feedback within this study, the clinicians receive contextualized feedback of the client and caregiver measures either weekly or every 90 days. In order to implement the CFIT program, the CEPI group paired with a Crisis in Usual Care 12 child therapy service, called the Providence Corporation. The CFIT trainers instructed the Providence clinicians and their supervisors in how to use the various measures involved in the project. The trainers also educated the clinicians about common factors, e.g., therapeutic alliance and client satisfaction. The common factors provided a basis in the development of some of the CFIT measures. Participants The data were collected from June 2006 through December 2008. The clinicians, N=240, provided data for 7386 sessions. Of the 7386 sessions, 7267 sessions had information about whether any time was spent on a crisis. Of these sessions with crisis information, 5635 sessions spent no time spent dealing with a crisis, 1070 sessions spent a little time dealing with a crisis, 311 sessions spent about half of the time dealing with a crisis, and 251 sessions spent most or all of the sessions dealing with a crisis. The clients consisted of N=629 youth who had therapy sessions and data on these sessions. The children ranged from age 11 to age 18. The average age was 14.7 years. Fifty-five percent of the clients were males, and 45% of the clients were female. Data was provided for an average of 12 sessions per youth. The clinician participants who provided session data was N=240. Seventy-nine percent of the clinicians were female and averaged 37.5 years of age. The clinicians reported data for an average of 31 sessions each. The clinicians also provided data for an average of 3 clients each. The caregivers of the youth participated in about 34% of the total session data. We have data on the caregiver’s participation in the session for 2500 of the 7386 total sessions. Measures Session Report Form (SRF) Crisis in Usual Care 13 The Session Report Form (SRF) is a self-report checklist the clinicians fill out after every session with the client. It contains a checklist of issued that might be discussed during the session. Examples of these issues include behavioral issues, family issues, client hope for the future, caregiver satisfaction with life, etc. Clinicians have the option to answer that the topic was addressed, was not addressed, or was the focus of the session. Other items on the SRF allow the clinician to report the length, location, session participants, date, and overall rating of the session. The SRF also contains an item pertaining to crises. The item reads, “How much time in this session did you spend dealing with a crisis?” The possible answer choices include ‘none,’ ‘a little,’ ‘about half,’ and ‘most or all’ of the session. Symptom Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS) The Symptom Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS), whose first page is shown in Appendix A, measures the severity of the client’s emotional and behavioral problems. It is an important indicator for measuring the treatment progress. It contains 33 items and has two subscales for internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Examples of these internalizing and externalizing items include ‘feel worthless,’ ‘cry easily,’ ‘throw things when mad,’ and ‘threaten or bully others.’ Some items do not pertain to either internalizing or externalizing symptoms. Examples of these symptoms include ‘think you don’t have friends’ ‘use drugs,’ and ‘drink alcohol.’ The clinician, client, and caregiver filled out separated forms of the SFSS. The items on the forms have 5 choices on a five-point Likert scale: never, hardly ever, sometimes, often, very often. For clinician and caregiver forms, the scores range from 42 to 105. For the youth form, the scores can range from 32 to 107. Therapeutic Alliance Questionnaire Scale (TAQS) Crisis in Usual Care 14 The Therapeutic Alliance Questionnaire Scale (TAQS) measures therapeutic alliance (TA). TA is a construct describing the bond between the client and the clinician, agreement on goals between client and clinician, and agreement on tasks of therapy between client and clinician (Bordin, 1979). The clinicians, caregivers, and clients completed the three versions of the form. The first pages of these forms are shown in Appendix A. The clinicians reported on items for their alliance between the clinician and youth client and between the clinician and adult caregiver. The caregivers reported on their alliance with the clinician, and the youth also reported on their alliance with the clinician. The caregiver and client forms contain 13 items pertaining to the bond and goals of therapy. The raters scored items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not at all,’ ‘only a little,’ ‘somewhat,’ ‘quite a bit,’ and ‘totally.’ The clinician form only contains 2 items that ask how the clinician would rate the working alliance between the client and the caregiver. The possible answer choices include ‘poor,’ ‘poor,’ ‘satisfactory,’ ‘good,’ and ‘excellent.’ For all forms the respondents’ scores for all the items are averaged to yield an overall TA rating ranging between 1 and 5. Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CSQ) The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CSQ) measured the extent to which the caregivers experienced distress in caring for a child with emotional or behavioral problems. The caregiver self reported problematic events or behaviors that resulted from caregiver burden. Caregiver burden has been a construct associated with how children utilize mental health services (Brannan & Helfinger, 2001). The first page of the CSQ is shown in Appendix A. It has 21 items to assess strain over a 1-month period. The measure includes an objective subscale and an internalizing subjective subscale. Examples of these items include ‘worried about future,’ Crisis in Usual Care 15 ‘financial strain,’ ‘sad or unhappy,’ and ‘tired or strained.’ The items range from 1(not at all a problem) to 5 (very much a problem). Data Collection The participants each had a particular implementation schedule required of them, as shown in Table 1. The clinicians filled out the Session Report Form (SRF) weekly after each session. They also filled out the symptom severity and alliance measures alternating every 2 weeks. The clients filled out the alliance and symptom severity forms every 2 weeks for the first 4 months. After the first four months, they filled out the forms every 4 weeks. The caregivers also had the same implementation schedule for the alliance and symptom severity measures. The caregivers filled out the caregiver strain measure every 8 weeks for the entire length of treatment. After the participants have recorded their measures, the clinicians returned the forms to CFIT staff. The caregiver and client sealed their responses in an envelope so that their answers would not be influenced by the presence of the clinician. Although the participants were asked to adhere to the implementation schedule, data were missing for various sessions. The most common reason for missing measures was because the client and clinician did not meet. Other reasons for missing data measures were that the respondent refused or there was not enough time. Analysis Plan The first part of the analysis created two different definitions of a crisis session based upon the question in the SRF asking about time spent on a crisis. One definition incorporated any session where some time was spent dealing with crisis (‘a little,’ ‘about half,’ or ‘most or all’). A non-crisis sessions was when no time was spent dealing with crisis. The second definition of a crisis session included only the sessions when ‘about half’ or ‘most or all’ of the Crisis in Usual Care 16 session was spent dealing with a crisis. A non-crisis session would be any session when no time or just a little time was spent dealing with a crisis. Next, we used binomial logistic regressions to determine the factors likely to occur during a session with a crisis. The independent variables were the various characteristics of the session: therapeutic alliance, child symptoms and functioning, caregiver strain, and number or type of session topics discussed. We will also examine specific client and clinician characteristics, such as age, gender, number of sessions, and topics discussed. The dependent variable is whether or not a crisis has occurred within the session. The first definition of a crisis (‘none’ versus ‘a little,’ ‘about half,’ or ‘most or all’) was used to explore the relationships of the covariates. Each covariate was tested in a single-covariate logistic regression model. If the covariate showed a significant association, then the significant covariates were tested in a multiple-covariate logistic regression. The second definition of a crisis (‘none’ and ‘a little’ versus ‘about half’ or ‘most or all’) was used to further examine the significant associations. Results The findings of this study describe the characteristics that are likely to occur during a crisis within a therapeutic session based upon three levels of analysis: the session level, the clinician level, and the client level. At the clinician and client characteristics were analyzed separately to determine their association with crises. The client and clinician characteristics examined, such as age and gender, were fixed effects because they cannot change across sessions. These covariates were analyzed separately from the session-level covariates since the session covariates change across the course of treatment. Session Level Therapeutic Alliance Crisis in Usual Care 17 A binary logistic regression was conducted to determine the covariates of a crisis occurrence within a session. The covariates at the session level include therapeutic alliance, symptoms and functioning, caregiver strain, number of topics addressed, and type of topics addressed. Each covariate was assessed individually within its own logistic regression model to determine their unadjusted associations with a crisis. Table 2 displays the results of these logistic regressions. For the unadjusted logistic regression for individual covariates, the higher the TA, as rated by the clinician and client, the less likely a crisis occurred within a session. The TA between the clinician and youth and between the clinician and caregiver, as rated by the clinician, both showed a significant relationship with the occurrence of a crisis (OR=0.68, p<0.001 CI: 0.61, 0.77; OR=0.82, p=0.002, CI: 0.72, 0.93). The TA between the clinician and youth, as rated by the youth, also displayed a significant association with a crisis (OR=0.88, p=0.02, CI: 0.79, 0.98); however the clinician-caregiver TA, as rated by the caregiver, did not show a significant relationship (p=0.62). With the significant TA covariates, a three-covariate logistic model was conducted, as shown in the right-hand column of Table 2. The result showed that the model was significant (p<0.001) with the following equation: Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = 0.371 + (-0.04 )* Youth TA + (0.068 )*Clinician-caregiver TA + (-0.423)* Clinician-client TA (p=0.35) (p=0.51) (p=0.44) (p<0.001) The clinician-client TA, as rated by the clinician, remained a significant covariate of a crisis (OR= 0.655, p<0.001, CI: 0.550, 0.780). However, the clinician-client TA rated by the Crisis in Usual Care 18 client and the clinician-caregiver TA rated by the clinician were no longer significant covariates (p=0.51, p=0.43). Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS) Next, we conducted a binary logistic regression to determine the significance of the covariate variables of symptoms and functioning of the client. The measures came from the SFSS and were rated by the client, clinician, and caregiver. Again, each of the covariates was evaluated individually in an unadjusted logistic regression single-predictor model, as shown in Table 3. All three raters’ SFSS scores were significantly associated with the occurrence of a crisis. As expected, crises were more likely to occur within session with more severe symptom scores as rated by the client, clinician, and caregiver (OR=1.28, p<0.001, CI: 1.12, 1.46; OR=2.23, p<0.001, CI:1.91, 2.59; OR=1.51, p<0.001, CI: 1.27, 1.80). These covariates were then tested in a three-covariate logistic regression model. The model was significant (p<0.001). In the model, the SFSS scores, as rated by the clinician and caregiver, remained significant covariates of a crisis within a session (OR=1.94, p<0.001, CI: 1.49, 2.52; OR=1.25, p=0.04, CI: 1.01, 1.55), while the SFSS score rated by the client was no longer a significant covariate (p=0.293). Another adjusted logistic regression was conducted with the significant covariates in the previous model: the SFSS scores as rated by the clinician and the SFSS scores as rated by the caregiver. The model was a significant (p<0.001) with the following equation: Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = (-3.17) + (0.70)* Clinician-rated SFSS + (0.13)*Caregiver-rated SFSS (p<0.001) (p<0.001) (p=0.23) The clinician-rated SFSS measure remained a significant covariate. When compared to less severe symptoms, more severe symptoms were more likely to occur during a crisis session Crisis in Usual Care 19 (OR=2.00, p<0.001 CI: 1.58, 2.54). The caregiver-rated SFSS measure was no longer a significant covariate the clinician-rated SFFS was tested in the same model (p=0.23). Caregiver Strain The caregiver strain measure was the next covariate tested in a logistic regression model. There were N=543 sessions with the measurement of caregiver strain. Contrary to our hypothesis, caregiver strain was not a significant covariate of a crisis within a session (p=0.106). Topics Discussed When the number of topics discussed in a session was tested in a logistic regression model, it was a significant covariate of a crisis. As shown in Table 4, the more topics discussed within a session, either addressed or focused on, the more likely a crisis occurred within the session (OR=1.15, p<0.001, CI: 1.13, 1.17). Another covariate based upon topics discussed within a session was tested in a logistic regression model. The variable tested was the SRF index measuring topics relating to personal or caregiver issues rather than problem-oriented topics. It was a significant predictor of a crisis within a session. The higher the SRF index, or the more non-problem oriented topics addressed or focused on, the more likely a crisis occurred within a session (OR=1.12, p<0.001, 1.11, 1.14). The two covariates detailing the number and type of topics discussed were tested within a logistic regression in the right-hand column of Table 4. The model was a significantly associated with the occurrence of a crisis within a session (p<0.001) with the following equation: Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = (-2.707) + (0.168)* Number of Topics + (-0.032)*SRF Index (p<0.001) (p<0.001) (p=0.04) Crisis in Usual Care 20 In the model the higher number of topics discussed, the more likely the session had a crisis (OR=1.18, p<0.001, CI: 1.15, 1.22). However, the SRF index no longer remained a significant covariate since its coefficient changed by more than 10%. This variable may be an intervening variable in the relationship of number of topics discussed and the occurrence of a crisis (OR=0.97, p=0.04, CI: 0.94, 1.00). Combined Models Table 5 and Table 6 show the combined covariates used in two logistic regression models. The SFSS and TA scores could not be tested in the same logistic regression model because they were collected on different session dates. Thus, both SFSS and TA were tested in separate models with the number of topics. Table 5 shows the logistic regression results of a model testing the number of topics and TA, as rated by the clinician. The model was significant with the following equation: Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = (-0.86) + (-0.47)* Clinician-rated TA + (0.15)*Number of Topics (p<0.001) (p<0.001) (p<0.001) Table 13 shows the predicted probabilities of a crisis given hypothetical data of the TA score and the number of topics discussed. The probabilities were calculated using the preceding equation. In this model both the TA, as rated by the clinician, and number of topics discussed remained significant covariates (OR=0.62, p<0.001, CI: 0.55, 0.70; OR=1.15, p<0.001, CI: 1.13, 1.19). Sessions with higher clinician-rated TA had about 40% lower odds of having a crisis within a session, and sessions with more topics discussed had about 15% higher odds of having a crisis. Crisis in Usual Care 21 Table 6 shows the logistic regression model with the number of topics and SFSS score, as rated by the clinician. The model was a significantly associated with occurrence of crises (p<0.001) with the following equation: Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = (-3.86) + (0.71)* Clinician-rated SFSS + (0.11)*Number of Topics (p<0.001) (p<0.001) (p<0.001) Both the SFSS score and the number of topics remained significant covariates with the occurrence of a crisis (OR= 2.03, p<0.001; OR=1.12, p<0.001, CI: 1.10, 1.15). Compared to less severe symptoms, more severe symptoms rated by the clinician had over two times higher odds of occurring within a crisis. Also, the higher the number of topics discussed in a session, the more likely a crisis occurred within a session Clinician Level At the clinician level several fixed effects were tested in logistic regression. As shown in Table 7, the clinician’s age was tested as a covariate in a logistic regression model, and, as expected, it was a significant covariate (OR=1.02, p<0.001, CI: 1.02, 1.03). The older the clinician, the more likely a crisis occurred within a session. Next, two other one-covariate logistic regression models were conducted for the number of clients per clinician and average number of topics discussed per clinician. The number of clients per clinician and the number of topics per clinician were significant covariates for a crisis within a session. The smaller the number of clients the more likely a crisis would occur within a session (OR=0.97, p<0.001, CI: 0.96, 0.99). Also, the higher the average number of topics discussed per clinician the more likely a crisis would occur within a session (OR=1.14, p<0.001 CI: 1.12, 1.17). Lastly, the number of Crisis in Usual Care 22 sessions per clinician was tested in logistic regression model, but it was not a significant covariate of crises (p=0.34). The age of the clinician, the number of clients per clinician, and the number of topics per clinician were then tested in a two-covariate logistic regression model. The number of topics per clinician and number of clients per clinician remained significant covariates of a crisis within a session (OR=1.16, p<0.001, CI: 1.13, 1.19; OR=0.96, p<0.001, CI: 0.94, 0.98). However, the age of the clinician was not a significant covariate (p=0.162). The model had a significant association with the occurrence of crises (p<0.001) with the following equation. Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = (-2.56) + (0.14)* Number of topics/clinician + (0.004)*Number of clients/clinician (p<0.001) (p<0.001) (p=0.64) The average number of topics discussed per session by clinician remained a significant covariate of the occurrence of a crisis (OR=1.15, p<0.001, CI: 1.12, 1.17). As in the previous model, the higher number of topics discussed, the more likely a crisis occurred. However, the number of clients per clinician was no longer a significant covariate (p=0.64). Client/Youth Level Lastly, client characteristics were tested individually in one-covariate logistic regression models. As shown in Table 8, the client’s age was a significant covariate of crises within sessions. The older the client, the more likely the session resulted in a crisis (OR= 1.04, p=0.02, Crisis in Usual Care 23 CI: 1.01, 1.07). The average number of topics discussed in a session by the client was also a significant covariate. The higher the average number of topics discussed by a client, the more likely the session had a crisis (OR=1.17 p<0.001, CI: 1.15, 1.19). However, the client’s gender was not a significant covariate of a crisis (p=0.072). The number of sessions per client was also not a significant covariate (p=0.901). Then a two-covariate logistic regression model was conducted with the client’s age and average number of topics discussed by the client. The model had a significant association with the occurrence of a crisis with the following equation: Predicted logit of (CRISIS) = (-3.16) + (0.03)* Client’s Age + (0.15)*Number of topics discussed by client (p<0.001) (p=0.06) (p<0.001) However, the number of topics discussed by the client remained a significant covariate (OR=1.17, p<0.001, CI: 1.15, 1.19). That is, the more topics discussed by the client, the more likely a crisis occurred within the session. The client’s age was no longer a significant covariate of a crisis (p=.06). Crisis Definition 2 Using the significant covariates, TA, SFSS, and topics discussed, a logistic regression model was tested using the second definition of crisis. This definition codes a non-crisis as any session spending either ‘none’ or ‘a little’ time dealing with a crisis. A crisis session is any session spending ‘about half’ or ‘most or all’ of the session dealing with a crisis. As shown in Table 9 and Table 10, all three covariates remained significant covariates of a crisis within a session. Crisis in Usual Care 24 In addition, topics discussed per session by the client and clinicians were also tested as covariates with the second definition (Table 10 and Table 11). These number of topics discussed by client and clinician remained significant predictors in the model. Discussion This paper examines the features of sessions, clients, and clinicians that were likely to occur during a crisis in treatment as usual in children’s mental health services. Sessions in which many topics were discussed were more likely to have a crisis than sessions with fewer topics discussed. This relationship also existed for individual clients and clinicians. Those individuals who discussed more topics per session were more likely to have a crisis. Although this relationship is not a causal association, several possible explanations exist. On the one hand, the crisis itself may involve the discussion of various issues involved in both the client’s life and client’s therapeutic process. On the other hand, the discussion of too many topics may create a sense of uncontrollability and provoke a crisis. Another explanation for the association might be that clients and clinicians who are prone to crises may have more troubling issues to discuss. Another finding of this study is the relationship between therapeutic alliance and a crisis session. Sessions with lower ratings of TA were more likely to have a crisis. This relationship can be expected given the importance of TA in child therapy outcomes (Kazdin, Whitley, & Marciano, 2005). Again the relationship between TA and a crisis session is not a causal one. Some explanations may be that higher TA buffers against the occurrence of a crisis, or a lower TA creates a condition vulnerable to crises. Another possibility may be that the crisis creates a lower TA, especially if the clients transfer their distress upon the relationship with the clinician. Crisis in Usual Care 25 Another significant finding of this study is the association between symptom severity and occurrence of a crisis. Sessions when the clinician rated higher client symptom severity had two times higher odds of having a crisis. This association is as predicted given that the definition of crisis may be the decline in psychological functioning (Kleepsies & Dettmer, 2000). Therefore, higher severity of symptoms could be one of the features of a crisis. Another possibility could be that the symptoms become more severe because of the crisis. When the number of topics was combined with either the symptom severity covariate or the therapeutic alliance covariate, each covariate kept their significant associations with the occurrence of a crisis. These significant associations also appeared when using a second, stricter definition of crisis. Confirming these associations with the second definition of crisis provided us with reliable evidence. Limitations of the study Caution must be used when interpreting the clinician-rated measures as significant covariates. Although the clinician-rated TA and clinician-rated symptom severity were significant covariates, these associations may be influenced by the clinicians’ perception of a crisis. The clinicians’ identification of a crisis may influence their subjective scores of the clients’ symptoms and therapeutic alliance. When TA and symptom measures, rated by the client and the caregiver, were tested as covariates with the clinician-rated measures, clinicianrated measures were more significantly associated with crises. This association makes sense given that clinicians rated the occurrence of a crisis. Thus, the clinician measures probably had a stronger association than the caregiver and client-rated measures because of the congruence in Crisis in Usual Care 26 raters. The client and caregiver-rated measures should not be discounted as covariates since they were significant when they were assessed individually. One main limitation of this study is the clinicians’ self report of a crisis. Using the clinicians’ perspective of a crisis limits the study in several ways. First, the clinician may not necessarily agree with the client’s perception of a therapeutic event (Fiedler & Rogge, 1989). Thus, the client or caregiver may not agree with the crises that the clinician identified. Furthermore, the definition of a crisis was not defined for the clinicians, and the clinicians could interpret the term in their own way. Since clinicians can act based upon their particular stylistic dimensions, (Castanerias et al., 2006), such as engagement and attentional dimensions, some clinicians may be more attentive or less critical of minor therapy changes. Although the subjectivity of the definition is a limitation, it is also a necessary way to deal with the term ‘crisis.’ As discussed previously, no consistent definition of a crisis in psychotherapy exists. Qualitative data on the exact essence of the crisis would be helpful in forming a description of a clinician’s perceived crisis. Another limitation of the study is the subjective nature of all the measures of the covariates. Since an objective observer did not report the measures, we relied on the judgments of the clients, clinicians, and caregivers. Objective observers can have different perceptions and judgments of such therapeutic elements as therapeutic alliance (Kazdin et al., 2005). Another limitation is the lack of predictive or causal associations between the covariates and crisis. Since we did not analyze the covariates in a session before the crisis, we cannot presume the covariates to be predictors of the crisis. Instead, the covariates represent correlates of a crisis session Crisis in Usual Care 27 The missing data also presents a limitation to our study. Since this study was implemented in a real-world setting, the participants did not always adhere to the protocol. Although the study accounted for over 7,000 sessions, sessions with incomplete data are not included in the data analysis. The missing data can be especially problematic if the occurrence of a crisis caused negligence in filling out the forms. Future Implications Future studies should address the limitations of this study. Qualitative data from both the clinician and the client would be helpful in identifying an agreed upon definition in treatment as usual settings. The results of this study have implications in treatment as usual. First, the results of this study emphasize the importance of measurement in treatment as usual. Secondly, these correlates can provide a basis for further examination of these covariates and of crises within session. Crisis in Usual Care 28 References American Counseling Association [ACA]. (2005). ACA Code of Ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author. Bambery, M., Porcerelli, J.H., & Ablon, J.S. (2007). Measuring psychotherapy process with the Adolescent Psychotherapy Q-set (APQ): Development and applications for training. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44, 405-422. Baumann, B.L., Kolko, D.J., Collins, K., Herschell, A.D. (2006). Understanding practitioners’ characteristics and perspectives prior to the dissemination of evidence-based intervention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 771-787. Bearsley-Smith, C., Sellick, K., Chesters, J., & Francis, K. (2008). Treatment content in child and adolescent mental health services: Development of the treatment recording sheet. Ad Policy Mental Health, 35, 423-435. Bickman, L. (2005). A common factors approach to improving mental health services. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 1-4. Bickman, L. (2008). A measurement feedback system (MFS) is necessary to improve mental health outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 1114-1119. Bickman, L. Riemer, M., Breda, C, & Kelley, S.D. (2006). CFIT: A system to provide a continuous quality improvement infrastructure through organizational responsiveness, measurement, training, and feedback. Report on Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 6, 86-87, 93-94. Bordin, E.S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 16, 252-260. Crisis in Usual Care 29 Brannan, A., & Helfinger, C. (2001). Distinguishing caregiver strain from psychological distress: Modeling the relationships among child, family, and caregiver variables. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10, 405-418. Castaneiras, C., García, F., Bianco, J.L., & Fernández-Alvarez, H. (2006). Modulating effect of experience and theoretical-technical orientation on the personal style of the therapist. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 587-593. Chorpita, B.F., Daleiden, E.L., & Weisz, J.R. (2005). Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11, 141-156. Fernández-Álvarez, H., García, F., Bianco, J.L., & Santomá, S.C. (2003). Assessment questionnaire on the personal style of the therapist PST-Q. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 10, 116-125. Fiedler, P., & Rogge, K.E. (1989). Study of processes of psychotherapeutical episodes and perspectives selected examples. Zeitschrift für klinische Psychologie, 18, 45-54. France, K. (2007). Crisis Intervention. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, LTD. Garland, A.F., Hurlburt, M.S., & Hawley, K.M. (2006). Examining psychotherapy processes in a services research context. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 13,30-36. Ivanov, I. (2007). Common problems in psychotherapy training for psychiatry residents. Journal of Psychiatric Practice,13, 184-189. Jacobs, D.G., Brewer, M., & Klein-Benheim, M. (1999). Suicide assessment: An overview and recommended protocol. In D. Jacobs (Ed.) The Harvard Medical School Guide to Suicide Assessment and Intervention (pp. 3-39). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kazdin, A.E. Whitely, M., & Marciano, P.L. (2006). Child-therapist and parent-therapist alliance and therapeutic change in the treatment of child referred for oppositional, Crisis in Usual Care 30 aggressive and antisocial behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 5, 436-445. Kleespsies, P.M. & Dettmer, E.L. (200). The stress of patient emergencies for the clinician: incidence, impact, and means of coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 1353-69. Kolko, D.J. (2006). Commentary: Studying usual care in child and adolescent therapy: It’s anything but routine. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 13, 47-52. McAdams, C.R. & Keener, H.J. (2008). Preparation, Recovery, Action: A conceptual framework for counselor preparation and response in client crisis. Journal of Counseling and Development, 86, 388-398. McKay, M.M., Hibbert, R., Hoagwood, K., Rodriguez, J., Murray, L., Legerski, J., & Fernandez, D. (2004). Integrating evidence-based engagement interventions into “real world” child mental health settings. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4, 177-186. Pollin, I. (1995). Medical Crisis Counseling: Short Term Therapy for Long-Term Illness. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Remley, T.P. (2004). Suicide and Law. In Suicide Across the Life Span: Implications for Counselors. D. Capuzzi (Ed.). (pp.185-208). New York: McGill. Roberts, A., & Everly, G.S. (2006). A meta-analysis of 36 intervention studies. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 6, 10-21. Safran, J.D., Crocker, P., McMain, S., & McMurry, P. (1990). The therapeutic alliance rupture as a therapy event for empirical investigation. Psychotherapy, 27, 154-165. Schiffman, J., Becker, K.D, & Daleiden, E.L. (2006). Evidence-based services in a statewide public mental health system: Do the services fit the problems? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 13-19. Crisis in Usual Care 31 Seligman, M.E.P. (1992). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. New York: W.H. Freeman Shirk, S.R. & Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 453-464. Slaby, R.G. (1998). Preventing youth violence through research-guided intervention. In P.K. Trickett & C.J. Schellenbach (Eds.). Violence Against Children in the Family and Community. (pp. 371-399). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Weersing, V.R., Weisz, J.R., & Donenberg, G.R. (2002). Development of the Therapy Procedures Checklist: A therapist-report measure of technique use in child and adolescent treatment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 31, 168-180. Crisis in Usual Care 32 Table 1. Implementation Schedule Form Rater(s) Session Report Form Schedule Clinician Weekly after each session -Clinician Every 2 weeks (SRF) Therapeutic Alliance Questionnaire Scale -Client Every 2 weeks for 4 months; then every 4 weeks -Caregiver Every 2 weeks for 4 months; then every 4 weeks -Clinician Every 2 weeks (TAQS) Symptom Severity & Functioning Scale -Client Every 2 weeks for 4 months; then every 4 weeks (SFSS) -Caregiver Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CQS) Caregiver Every 2 weeks for 4 months; then every 4 weeks Every 8 weeks Crisis in Usual Care 33 Table 2. Odds Ratio Results from Therapeutic Alliance Logistic Regressions Outcome is Crisis in Session (0/1) Sample Size N=1552 Unadjusted LR Adjusted LR Covariates Single Covariate 3 covariates together TAQS-C Clinician-client 0.68 (0.61, 0.77)** 0.66 (0.55, 0.78)** Clinician-caregiver 0.82 (0.717, 0.928)** 1.07 (0.90, 1.27) TAQS-Y 0.88 (0.787, 0.977)* 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) TAQS-A 1.04 (0.88,1.24) Note. Confidence limits are in parenthesis *p<0.05, **p<0.01 Crisis in Usual Care 34 Table 3. Odds Ratio Results from Symptom and Functioning Severity Logistic Regressions Outcome is Crisis in Session (0/1) Sample Size N=1635 Covariates Unadjusted LR Adjusted LR Adjusted LR Single Covariate 3 Covariates Together 2 Covariates Together SFSS-C 2.23 (1.91, 2.59)** 1.94 (1.49, 2.52)** 2.00 (1.58, 2.54)** SFSS-Y 1.28 (1.12, 1.46)** 0.91 (0.76, 1.10) SFSS-A 1.51 (1.27, 1.80)** 1.25 (1.01, 1.55)* 1.14 (0.93, 1.39) Note. Confidence limits are in parentheses *p<0.05, **p<0.01 Crisis in Usual Care 35 Table 4. Odds Ratio Results from Topics Logistic Regressions Outcome is Crisis in Session (0/1) Sample Size N=7231 Covariates Unadjusted LR Adjusted LR Single Covariate 2 Covariates Together # Topics Discussed x Session 1.15 (1.13, 1.17)** 1.18 (1.15, 1.22)** SRF Index 1.12 (1.11, 1.14)** 0.969 (0.941, 0.998)a Note. Confidence limits are in parentheses *p<0.05, **p<0.01 a lost significance because of >10% change in coefficient value Crisis in Usual Care 36 Table 5. Logistic Regression Analysis of Crisis in a Session with TA and Topics Covariates Covariates β SE β Wald’s df p eβ 95% CI 2 χ (odds ratio) Constant -0.86 0.25 12.13 1 <0.001 0.42 NA TAQS-C Clinician-client -0.47 0.06 60.37 1 <0.001 0.62 (0.55, 0.70) # Topics 0.15 0.01 162.54 1 <0.001 1.16 (1.13, 1.19) Discussed x Session Test χ2 df p Overall Model Evaluation χ2 215.60 2 <0.001 Goodness-of-fit test Hosmer & 6.06 8 0.64 Lemeshow Note. Sample Size N=2945 Cox and Snell R2=.071. Nagelkerke R2=0.107. NA=not applicable Crisis in Usual Care 37 Table 6. Logistic Regression Analysis of Crisis in a Session with SFSS and Topics Covariates Covariates β SE β Wald’s df p eβ 95% CI χ2 (odds ratio) Constant -3.86 0.22 337.71 1 <0.001 0.02 NA SFSS--Clinician <0.001 0.71 0.08 78.60 1 (1.74, 2.28) 2.03 # Topics 0.11 0.01 97.90 1 <0.001 1.12 (1.10, 1.15) Discussed x Session Test χ2 df p Overall Model Evaluation χ2 208.68 2 <0.001 Goodness-of-fit test Hosmer & 8.73 8 0.37 Lemeshow Note. Samples Size N=2958 Cox and Snell R2=.068. Nagelkerke R2=0.105. NA=Not applicable Crisis in Usual Care 38 Table 7. Results from Clinician Characteristics Logistic Regression Outcome is Crisis (0/1) N=4600 Covariates Unadjusted LR Adjusted LR Single Covariate 3 Covariates Together Clinician Age 1.02 (1.02, 1.03)** 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) # of Clients x Clinician 0.973 (0.959, 0.987)** 0.96 (0.94, 0.98)** # of Topics/Session x 1.14 (1.12, 1.17)** 1.16 (1.13, 1.19)** Clinician # of Sessions x 1.00 (.999, 1.00) Clinician Note. Confidence limits are in parentheses *p<0.05, **p<0.01 Adjusted LR 2 Covariates Together 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) 1.15 (1.12, 1.17)** Crisis in Usual Care 39 Table 8. Odds Ratio Results from Client Characteristics Logistic Regressions Outcome is Crisis (0/1) N=6349 Covariates Unadjusted LR Adjusted LR Single Covariate 2 Covariates together Client Age 1.04 (1.01, 1.07)* 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) Client Gender -0.11(0.80, 1.01) # of Topics/Session x 1.17 (1.15, 1.19)** 1.17 (1.15, 1.19)** Client # of Sessions x Client 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) Note. Confidence limits are in parentheses. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 Crisis in Usual Care 40 Table 9. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with TA and Topics Covariates Covariates β SE β Wald’s df p eβ 95% CI 2 χ (odds ratio) Constant -1.88 0.35 31.53 1 <0.001 0.14 NA TAQS-C Clinician-client -0.47 0.09 29.98 1 <0.001 0.63 (0.53, 0.74) # Topics 0.13 0.02 66.91 1 <0.001 1.14 (1.11, 1.18) Discussed x Session Test χ2 df p Overall Model Evaluation χ2 89.79 2 <0.001 Goodness-of-fit test Hosmer & 4.23 8 0.83 Lemeshow Note. Samples Size N=2945 Cox and Snell R2=0.03. Nagelkerke R2=0.069. NA=not applicable Crisis in Usual Care 41 Table 10. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with SFSS and Topics Covariates Covariates β SE Wald’s df p eβ 95% CI 2 β χ (odds ratio) Constant -5.32 0.34 250.80 1 <0.001 0.01 NA SFSS-Clinician <0.001 # Topics Discussed x Session Test Overall Model Evaluation χ2 0.80 0.12 42.84 1 0.09 0.02 28.52 1 χ2 df 84.48 2 2.22 (1.75, 2.82) <0.001 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) p <0.001 Goodness-of-fit test Hosmer & Lemeshow 11.15 8 0.19 2 Note. Sample Size=2958. Cox and Snell R =0.028. Nagelkerke R2=0.069. NA=not applicable. Crisis in Usual Care 42 Table 11. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with a Client Characteristic as Covariate Covariates β SE β Wald’s df p eβ 95% CI 2 χ (odds ratio) Constant -3.62 0.15 614.87 1 <0.001 0.03 NA # Topics 0.12 0.01 73.90 1 Discussed/Session x Client Test χ2 df Overall Model Evaluation χ2 71.85 1 Goodness-of-fit test Hosmer & 49.01 8 Lemeshow Note. Sample Size N=7267. Cox and Snell R2=0.01. <0.001 1.12 (1.10, 1.16) p <0.001 <0.001 Nagelkerke R2=0.023. NA=not applicable. Crisis in Usual Care 43 Table 12. Logistic Regression Analysis of a Crisis in a Session with a Clinician Characteristic as Covariate Covariates β SE β Wald’s df p eβ 95% CI 2 χ (odds ratio) Constant -3.28 0.15 495.54 1 0.001 0.04 NA # Topics 0.08 0.01 34.65 1 0.001 1.09 (1.06,1.12) Discussed/Session x Clinician Test χ2 df p Overall Model Evaluation χ2 33.57 1 <0.001 Goodness-of-fit test Hosmer & 78.78 8 <0.001 Lemeshow Note. Sample Size N=7267. Cox and Snell R2=0.005. Nagelkerke R2=0.011. NA=not applicable. Crisis in Usual Care 44 Table 13. Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session from Hypothetical Data of TA and Topics TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 1 0 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.209159365 1 1 -0.86 0.234692781 1 2 -0.86 0.262309356 1 3 -0.86 0.291935976 1 4 -0.86 0.323441643 1 5 -0.86 0.356634854 1 6 -0.86 0.391264513 1 7 -0.86 0.427024884 1 8 -0.86 0.463564698 1 9 -0.86 0.5005 1 10 -0.86 0.537429845 1 11 -0.86 0.573953528 1 12 -0.86 0.609687778 1 13 -0.86 0.644282404 1 14 -0.86 0.677433046 1 15 -0.86 0.708890173 1 16 -0.86 0.73846392 1 17 -0.86 0.766024904 1 18 -0.86 0.791501512 TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 1 20 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.836169639 1 21 -0.86 0.855449731 1 22 -0.86 0.872806019 1 23 -0.86 0.888350314 1 24 -0.86 0.902207795 1 25 -0.86 0.914510861 1 26 -0.86 0.925394093 1 27 -0.86 0.93499032 1 28 -0.86 0.943427686 1 29 -0.86 0.950827587 1 30 -0.86 0.957303356 1 31 -0.86 0.96295952 1 32 -0.86 0.967891525 1 33 -0.86 0.972185793 2 0 -0.86 0.141851065 2 1 -0.86 0.160838827 2 2 -0.86 0.181829696 2 3 -0.86 0.204891176 2 4 -0.86 0.230055119 2 5 -0.86 0.257309455 2 6 -0.86 0.28659075 2 7 -0.86 0.317778454 Crisis in Usual Care 45 TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 2 8 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.350691735 TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 2 30 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.933391964 2 9 -0.86 0.385089726 2 31 -0.86 0.942023912 2 10 -0.86 0.420675748 2 32 -0.86 0.949597623 2 11 -0.86 0.457105697 2 33 -0.86 0.956227915 2 12 -0.86 0.494000288 3 0 -0.86 0.093638212 2 13 -0.86 0.53096034 3 1 -0.86 0.106976855 2 14 -0.86 0.567583836 3 2 -0.86 0.121959896 2 15 -0.86 0.60348325 3 3 -0.86 0.138715477 2 16 -0.86 0.638301558 3 4 -0.86 0.157360484 2 17 -0.86 0.671725582 3 5 -0.86 0.177993686 2 18 -0.86 0.703495691 3 6 -0.86 0.200687983 2 19 -0.86 0.73341137 3 7 -0.86 0.225482099 2 20 -0.86 0.761332715 3 8 -0.86 0.252372253 2 21 -0.86 0.787178291 3 9 -0.86 0.28130451 2 22 -0.86 0.810920123 3 10 -0.86 0.312168669 2 23 -0.86 0.832576698 3 11 -0.86 0.344794577 2 24 -0.86 0.852204883 3 12 -0.86 0.378951724 2 25 -0.86 0.869891526 3 13 -0.86 0.414352746 2 26 -0.86 0.885745374 3 14 -0.86 0.450661085 2 27 -0.86 0.899889734 3 15 -0.86 0.487502604 2 28 -0.86 0.912456133 3 16 -0.86 0.524480411 2 29 -0.86 0.923579084 3 17 -0.86 0.561191721 Crisis in Usual Care 46 TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 3 18 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.597245246 3 19 -0.86 0.632277546 4 6 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.135638245 3 20 -0.86 0.665966927 4 7 -0.86 0.153943564 3 21 -0.86 0.698043826 4 8 -0.86 0.17422137 3 22 -0.86 0.728297124 4 9 -0.86 0.196549701 3 23 -0.86 0.756576329 4 10 -0.86 0.220973892 3 24 -0.86 0.782790028 4 11 -0.86 0.247498215 3 25 -0.86 0.806901316 4 12 -0.86 0.276078043 3 26 -0.86 0.828921083 4 13 -0.86 0.306613408 3 27 -0.86 0.848900061 4 14 -0.86 0.338944819 3 28 -0.86 0.866920433 4 15 -0.86 0.372852234 3 29 -0.86 0.883087655 4 16 -0.86 0.40805784 3 30 -0.86 0.897522967 4 17 -0.86 0.444232986 3 31 -0.86 0.91035686 4 18 -0.86 0.48100914 3 32 -0.86 0.921723655 4 19 -0.86 0.517992228 3 33 -0.86 0.931757179 4 20 -0.86 0.554779235 4 0 -0.86 0.060653903 4 21 -0.86 0.59097562 4 1 -0.86 0.069655065 4 22 -0.86 0.626211958 4 2 -0.86 0.079878426 4 23 -0.86 0.66015836 4 3 -0.86 0.091454782 4 24 -0.86 0.692535528 4 4 -0.86 0.104518264 4 25 -0.86 0.723121805 4 5 -0.86 0.119202922 4 26 -0.86 0.751756062 TA #Topics Intercept Predicted TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 Crisis in Usual Care 47 Score β= -0.47 β=0.148 β= -0.86 4 27 -0.86 Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.778336762 4 28 -0.86 0.802817861 4 29 -0.86 0.825202406 4 30 -0.86 0.845534735 4 31 -0.86 0.863892109 4 32 -0.86 0.880376464 4 33 -0.86 0.895106767 5 0 -0.86 0.038791134 5 1 -0.86 0.044702217 5 2 -0.86 0.051465816 5 3 -0.86 0.059189365 5 4 -0.86 0.067988917 5 5 -0.86 0.077988235 5 6 -0.86 0.089317246 5 7 -0.86 0.102109716 5 8 -0.86 0.116500002 5 9 -0.86 0.132618767 5 10 -0.86 0.15058758 5 11 -0.86 0.17051242 5 12 -0.86 0.192476203 5 13 -0.86 0.216530622 TA Score β= -0.47 #Topics Intercept β=0.148 β= -0.86 5 14 -0.86 Predicted Probability of a Crisis in a Session 0.242687753 5 15 -0.86 0.270912078 5 16 -0.86 0.301113728 5 17 -0.86 0.333143845 5 18 -0.86 0.366792937 5 19 -0.86 0.401792956 5 20 -0.86 0.437823499 5 21 -0.86 0.474522086 5 22 -0.86 0.511497973 5 23 -0.86 0.548348458 5 24 -0.86 0.584676265 5 25 -0.86 0.620106432 5 26 -0.86 0.654301218 5 27 -0.86 0.686971808 5 28 -0.86 0.717886094 5 29 -0.86 0.746872278 5 30 -0.86 0.773818574 5 31 -0.86 0.798669599 5 32 -0.86 0.821420312 5 33 -0.86 0.842108397 Crisis in Usual Care 48 Appendix A Figure 1a. Session Report Form-Side 1 ...................................................................................................... 49 Figure 1b Session Report Form-Side 2 ........................................................................................................ 50 Figure 2. TAQS-Clinician Rated ................................................................................................................... 51 Figure 3 TAQS-Client-rated ........................................................................................................................ 52 Figure 4. TAQS-Caregiver-rated .................................................................................................................. 53 Figure 6. SFSS-Client-Rated ......................................................................................................................... 55 Figure 7. SFSS-Caregiver-Rated ................................................................................................................... 56 Figure 8. Caregiver Strain Questionnaire ................................................................................................... 57 Crisis in Usual Care 49 Figure 1a. Session Report Form-Side 1 Crisis in Usual Care 50 Figure 1b Session Report Form-Side 2 Crisis in Usual Care 51 Figure 2. TAQS-Clinician Rated Crisis in Usual Care 52 Figure 3 TAQS-Client-rated Crisis in Usual Care 53 Figure 4. TAQS-Caregiver-rated Crisis in Usual Care 54 Figure 5. SFSS-Clinician-Rated Crisis in Usual Care 55 Figure 6. SFSS-Client-Rated Crisis in Usual Care 56 Figure 7. SFSS-Caregiver-Rated Crisis in Usual Care 57 Figure 8. Caregiver Strain Questionnaire