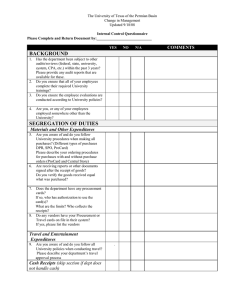

Institutional Effectiveness Handbook

advertisement