sample.essay.2328.2.doc

advertisement

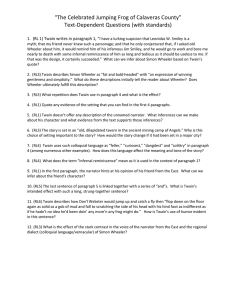

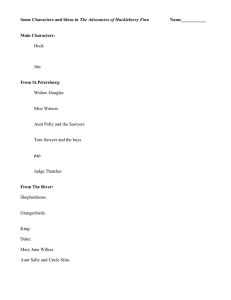

Smith 1 John Smith Mr. Jeff Lindemann English 2328 July 16, 2009 Twain Practices What He Preaches In 1895 Mark Twain, thirty years after he wrote “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” in 1865, wrote an informative essay entitled “How to Tell a Story.” In the essay he articulates the guidelines for telling a humorous oral tale. A humorous story, according to Twain, depends on one factor: “the manner of the telling” (1). In fact, the “manner” is more important than the “matter.” The reader must wonder if Twain’s standards for telling a story also apply to writing a story. Obviously, some problems arise when attempting to textualize the features of an oral rendition into the written version. Twain, however, a master at his craft, incorporates the features of the oral telling into the written telling of his celebrated frog. He does indeed “practice what he preaches.” In “Frog,” Twain incorporates the features he explains in “How to.” The story has no theme or plot, is told gravely, slurs the point, drops studied remarks, and incorporates a pause. First, a humorous story requires no theme or plot. In “How to” Twain explains that a humorous story is “spun out to great length and may wander around as much as it pleases and arrive nowhere in particular” (1). Furthermore, he writes, “To string incongruities and absurdities together in a wandering and sometimes purposeless way, and seem innocently unaware that they are absurdities is the basis of the American art” (3). The New England narrator in “Frog” describes Simon Wheeler’s story as one that would “bore me to death with some exasperating reminiscence of him as long and tedious as it should be useless to me” (104). Even the name “Wheeler” implies that he (Wheeler) will go round and round—eventually arriving nowhere. In fact, once Wheeler gets started, we don’t even hear about the frog until half way through his Smith 2 “wandering.” Furthermore, the New England narrator writes that Simon Wheeler “reeled off the monotonous narrative” (104). Perhaps the best example of Wheeler’s monotonous storytelling occurs when he discusses Jim Smiley’s betting habits in increasing absurdity as he ranges from horse racing to the death of Parson Walker’s sick wife. Second, Twain writes that the storyteller should tell the tale “gravely” (1). Twain instructs: “[T]he teller does his best to conceal the fact that he even dimly suspects that there is anything funny about it [the tale]” (1). The New England narrator describes Wheeler as he tells his tale: He never frowned, he never changed his voice from the gentle-flowing key to which he tuned his initial sentence, he never betrayed the slightest suspicion of enthusiasm; but all through the interminable narrative there ran a vein of impressive earnestness and sincerity, which showed me plainly that, so far from his imagining that there was anything ridiculous or funny about his story, he regarded it as a really important matter . . . . (104) Simon Wheeler perfectly dramatizes Twain’s view of the “grave” storyteller who does not realize his own story is funny. The reader laughs at the storyteller—not the story. Third, Twain believes that another feature of the humorous story is slurring the point. The reader has to wonder if “Frog” even has a point. If the story does, the narrator certainly does not know it for he does not state it. The reader is left wondering, “Where’s the frog?” Even the mysterious trickster says about Smiley’s frog, “Well . . . I don’t know p’ints about that frog that’s any better’n any other frog” (107). Perhaps the point of the story, if it even has one, is that we should be suspicious of strangers because they sometimes outfox us if we are too naïve. This point is slurred at the end of the tale as Wheeler happily begins to tell the New Englander about a “yaller one-eyed cow that didn’t have no tail, only a stump like a bannanner . . .” (107). Smith 3 Yet another feature Twain reveals in “Frog” is the “dropped remark.” In “How to”, Twain advises “the dropping of a studied remark apparently without knowing it, as if one were thinking aloud” (3). In “Frog” Wheeler “drops” statements such as “Smiley said all a frog wanted was education, and he could do “’most anything—and I believe him” (106). The ignorant Wheeler actually makes an important remark about the importance of education, yet he does not realize that his “studied remark” is significant. A final feature of the humorous story is the pause. Twain creates this pause with a mark of punctuation—the dash. This pause ends the “rambling and disjointed story” (1) with a “nub, point, [or] snapper” (1). Twain writes: The pause is an exceedingly important feature in any kind of story, and a frequently recurring feature, too. It is a dainty thing, and delicate, and also uncertain and treacherous; for it must be exactly the right length—nor more and no less or it fails of its purpose and makes trouble. If the pause is too short the impressive point is passed, and the audience have had time to divine that a surprise is intended—and then you can’t surprise them, of course. (3) In the frog tale, Wheeler ends the story by saying, “And then he see how it was, and he was the saddest man—he set the frog down and took out after that feller, but he never ketched him. And—” (107). And with the pause, his story ends as the reader is left wondering the point of the tale. In “How to Tell a Story,” Twain reflects on the humorous tale after delineating its features: “The humorous story is strictly a work of art—high and delicate art—and only an artist can tell it” (1). Indeed Mark Twain proves himself an artist as he incorporates the oral features of a humorous tale into the written account of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” Smith 4 Works Cited Twain, Mark. “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. The Norton Anthology of American Literature. 7th ed. Ed. Nina Baym, et al. 5 Vols. New York: Norton, 2007. Vol. C: 104-08. Print. ---. “How to Tell a Story.” Jeff Lindemann’s Learning Web. Houston Community College, n.d. Web. 10 July, 2010.