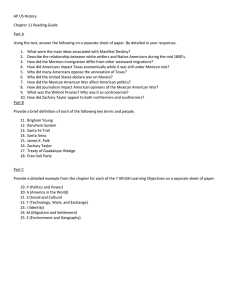

HCCelmariachiques.doc

advertisement

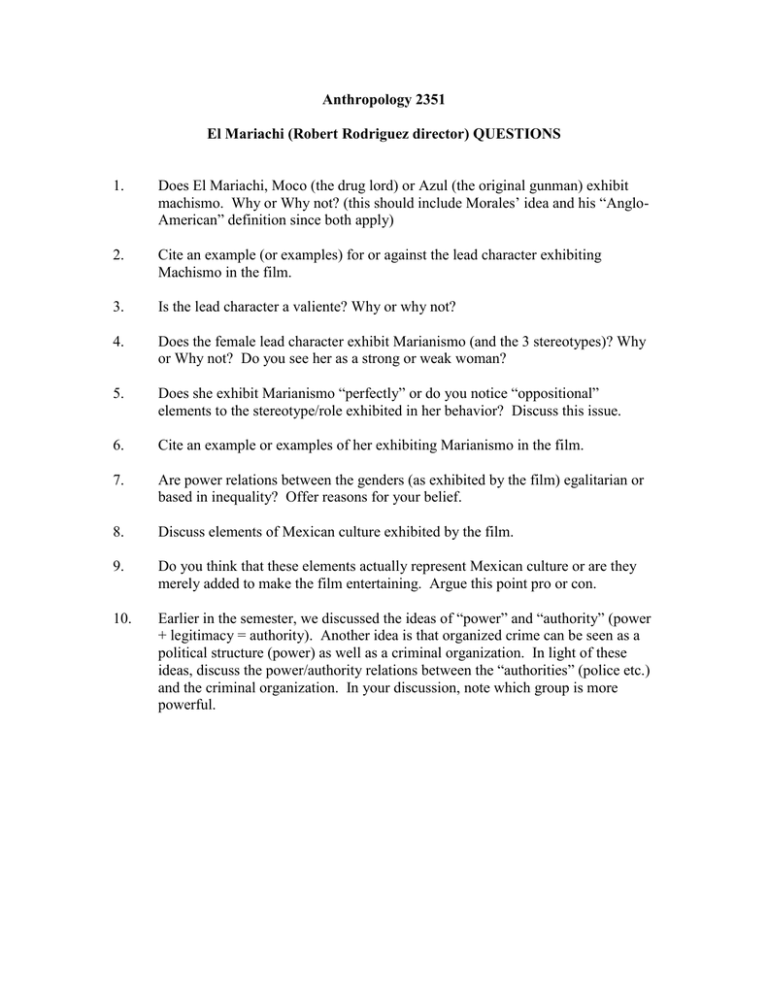

Anthropology 2351 El Mariachi (Robert Rodriguez director) QUESTIONS 1. Does El Mariachi, Moco (the drug lord) or Azul (the original gunman) exhibit machismo. Why or Why not? (this should include Morales’ idea and his “AngloAmerican” definition since both apply) 2. Cite an example (or examples) for or against the lead character exhibiting Machismo in the film. 3. Is the lead character a valiente? Why or why not? 4. Does the female lead character exhibit Marianismo (and the 3 stereotypes)? Why or Why not? Do you see her as a strong or weak woman? 5. Does she exhibit Marianismo “perfectly” or do you notice “oppositional” elements to the stereotype/role exhibited in her behavior? Discuss this issue. 6. Cite an example or examples of her exhibiting Marianismo in the film. 7. Are power relations between the genders (as exhibited by the film) egalitarian or based in inequality? Offer reasons for your belief. 8. Discuss elements of Mexican culture exhibited by the film. 9. Do you think that these elements actually represent Mexican culture or are they merely added to make the film entertaining. Argue this point pro or con. 10. Earlier in the semester, we discussed the ideas of “power” and “authority” (power + legitimacy = authority). Another idea is that organized crime can be seen as a political structure (power) as well as a criminal organization. In light of these ideas, discuss the power/authority relations between the “authorities” (police etc.) and the criminal organization. In your discussion, note which group is more powerful. NOTES AND TERMS FOR EL MARIACHI Valiente—definition—valiant, courageous and brave Greenberg claims that this term refers to an individual involved in a blood feud. In his text on rural Mexico, it is implied that this is an honor based (honor has been lost by the individual in question) idea dealing with revenge. Events such as the loss of one’s land to a rich landowner or politics can be contributing factors in creation of a valiente. Greenberg notes in his text that individuals were being killed and that one man (Emiliano) had been made a “marked” man as part of a political conflict. Emiliano’s two choices were to become a valiente and seek revenge or his own death (essentially to accept death as the probable outcome), or he could flee (to protect other members of his family or to be a coward). In the region Greenberg works with, it is a problem to be seen as a coward. It should be noted that fleeing to protect ones family is only somewhat accepted by others and there will always be those who would label it cowardly. Machismo—there are many varying definitions Bacigalupe—machismo is often used to explain the “violence” that Latino men exert over women (despite gender violence being found throughout the world). Denis Brandt, Fand and Quiroz—agree and say that machismo is the underlying element in the violence exerted against women. Quiroz—sees it as similar to racism and classism because it causes inequality. Morales—says it refers to a man’s responsibility to provide for, protect and defend his family. His loyalty and sense of responsibility to family, friends and community make him a good man Morales’ “Anglo-American” definition—it describes sexist male-chauvinist behavior Guttman claims that many of the images that anthropologists have been creating about the Mexican working class are erroneous and harmful to the populace. A typical Mexican man is often (stereotypically) portrayed as a hard drinking philandering macho, an idea that ignores the practice of fatherhood by most Mexican men. He notes that macho can contain elements of “the brutish,” “the cowardly,” or “the gallant” depending upon the era and the sector of Mexican society. According to his ethnography women in Mexico City often acknowledge the presence of machos, but that husbands and sons are seen as different (exceptions to the macho rule). It should be observed here that it appears that individuals who are not liked by the community or commit some “macho” appearing acts may acquire this label. Essentially, it is “the Other” (not “us”) who is seen as being macho (there may, of course, be actual machos). Many Mexican men are aware of their portrayal in the Social Sciences (“Anglo-American” Machismo), but the reality is that the beliefs and practices of many men do not match up to this image. The Social Science view does influence some of the populace (male and female) and can influence behavior (after all intellectuals/authorities are claiming it to be true). Marianismo—is seen as the “cult” of long-suffering Latin American women. The stereotype concerning women is that they are 1) submissive 2) self-sacrificing 3) longsuffering. Modern (and in some cases historic) Latin American women are involved in political movements and act as leaders on occasion. This is seen as a break from these traditional roles.