Final Thesis

advertisement

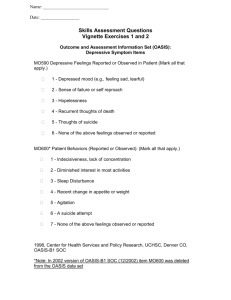

Running Head: PARENT AND CHILD DEPRESSION Relation between parent and child depression: Sex, age, pubertal status, and parent-child conflict as moderators Claire E. Borgschulte Vanderbilt University Research Advisors: Sarah A. Frankel, M.S., and Judy Garber, Ph.D. Abstract Children of depressed parents are at increased risk for developing depression themselves. Children’s sex, age, pubertal development, and parent-child conflict all have been shown to be related to depressive symptoms in children. The current study examined the relation between parental depression and children’s depressive symptoms, and explored possible moderators including children’s sex, age, pubertal development, and parent-child conflict. Participants were 227 parent-child dyads; of these, 129 parents were in treatment for depression (high risk); the remaining 98 parents were lifetime free of depression (low risk). Linear regression analyses revealed that high-risk children reported significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms than low-risk children. Sex significantly moderated the relation between risk and children’s depressive symptoms, such that high-risk girls reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than low-risk girls. Pubertal development also was a significant moderator, whereas age was not. More advanced pubertal development was associated with higher depressive symptoms in the high-risk group, but not in the low risk group. Finally, the relation between risk and children’s depressive symptoms also was moderated by parent-child conflict; the relation between parent and child depression was stronger in high as compared to low conflict dyads. Thus, children of depressed parents who were female, more advanced pubertally, or had greater parent-child conflict may be at increased risk for depression and therefore should be targeted for intervention. Offspring of depressed parents are at increased risk for emotional and behavioral problems, especially depression, compared to children of non-depressed parents (Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Hammen & Brennan, 2003; Lieb, Isensee, Hofler, Pfister, & Wittchen 2002). Children of depressed mothers are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression as are children of non-depressed mothers (Hammen & Brennan, 2003); 40% of children of affectively ill parents experience a major depressive episode by age twenty (Beardslee et al., 1998). The purpose of the current study was to examine possible moderators of the link between current major depressive disorder (MDD) in parents and children’s depressive symptoms. Several factors have been associated with depression in children and adolescents, including children’s sex, age, pubertal development, and conflict with the depressed parent. The extent to which these risk factors moderate the relation between parental depression and child depressive symptoms is less clear, however. Sex Depression is more prevalent among females than males (Bouma, Ormel, Verhulst, & Oldehinkel, 2007; Hankin & Abramson, 1999). After age fifteen, females are twice as likely as males to experience a major depressive episode (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000). One possible explanation for this sex difference is that females may be more sensitive to interpersonal stressors than males (Leadbeater, Sidney, & Quinlan, 1995). Indeed, Gore, Asletine and Colton (1993) found that high levels of interpersonal caring and involvement in the problems of others accounted for 25% of this sex difference in depression. Females also may exhibit a more negative cognitive style, which would make them more vulnerable to depression. For example, Hankin and Abramson (2002) showed that girls’ higher levels of negative cognitions including negative attributional style and self-perceptions (especially about appearance), accounted for elevated levels of depressive symptoms. The findings on sex differences in depression among offspring of depressed parents, however, have been mixed. Some studies have found that female offspring of depressed parents are more likely to develop depression than males (Cortes, Fleming, Catalano, & Brown, 2006; Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1995). Daughters of depressed mothers may be more likely than sons to model their mothers’ depressive cognitions and behavior, and increasingly identify with their depressed mother over time (Hops et al., 1996). Moreover, girls may be socialized to develop characteristics typical of depression, such as helplessness, submissiveness, and emotionfocused coping (Hops et al., 1996). In contrast, other studies have not found sex differences in the relation between parents’ and children’s depression (e.g., Brennan, LeBrocque, & Hammen, 2003). Thus, being female is associated with increased risk for depression, but whether the relation between parent and child depression varies by sex remains to be explored. Age The relation between parent and child depression also may vary as a function of children’s age. Older daughters of depressed mothers show more depressive symptoms than both same-age peers of non-depressed mothers and younger daughters of depressed mothers (Hops et al., 1990). In addition, onset of depression is earlier for children of depressed parents (mean age 12-13) than for children of non-depressed parents (mean age 16-17; Weissman et al., 1987). Thus, symptoms of depression may onset at an earlier age in offspring of depressed parents, and continue to worsen over time, leading older children of depressed parents to experience more severe depressive symptoms than their non-depressed counterparts. Additionally, child sex and age may interact to predict children’s risk for depressive symptoms. Sex differences in the rates of depression begin to emerge during early adolescence, with at least twice as many adolescent girls as boys displaying depressive symptoms (Hankin et al., 1998; Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994). Hankin and colleagues found that the rates of depression increased between the ages of 15 and 18 years (from 2.7% to 16.8%, respectively), and this increase was greater for girls (from 4.4% to 23.2%) than for boys (from 1% to 10.7%). Some studies have shown that preadolescent boys have higher rates of depression than preadolescent girls (Rutter, 1986), whereas others have not observed this pattern (Kashani et al., 1982). The extent to which sex and age independently and then together potentially moderate the link between parent and child depression in children of depressed parents is not known. Maternal depression may be more strongly associated with girls’ depressive symptoms than with boys’ as children enter adolescence (Cortes et al., 2006), but this possibility needs to be addressed empirically. Pubertal Development Pubertal development also has been linked with depression (Angold, Costello, & Worthman, 1998). Although age and puberty are related, and both have been linked to increases in depression in girls, their independent relation to depression in high risk youth is less clear. The gender intensification hypothesis proposes that following puberty, the disparity between the stereotype of the “perfect” female body and girls’ actual bodies increases, which may, in part, explain the rise in depressive symptoms among adolescent girls (Hankin & Abramson, 1999). That is, for girls as their bodies mature and conform less to the “ideal female physique” (e.g. thin, small hips) puberty may become a stressor. In contrast, puberty in males typically results in a smaller disparity between their bodies and the “ideal male” physique (e.g. muscular, tall). In addition, females may be more sensitive or reactive to life stressors and transitions, so the biological and psychosocial changes associated with early adolescence may trigger more distress for females than for males (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001). Timing of puberty, that is, the interaction between a child’s age and the onset of puberty, has been linked with the onset of depressive symptoms. In a longitudinal study, Ge and colleagues (2001) found that pubertal status in seventh grade predicted later depressive symptoms, whereas pubertal status in eighth through tenth grade did not predict depressive symptoms over time. Thus, early maturation when divergent from the norm may provoke social ridicule or rejection, which, in turn, may increase the chances of depressive symptoms. Ge et al. (2001) also showed that early maturing girls had higher levels of depressive symptoms than other girls and boys their age, and suggested that early maturing girls with depression were at a greater risk for recurrent episodes later in life. Thus, early maturation may be particularly associated with depression in girls. The relations among age, pubertal timing, and depressive symptoms also vary by sex. For example, Angold and colleagues (1998) reported that reaching mid-puberty (i.e., girls have begun menstruation, are growing rapidly, and show notable breast development) was the best predictor of depression, regardless of how quickly or at what age girls reached this stage. Moreover, depressive symptoms in boys began to decrease once they entered puberty, and there was a sharp decrease in boys’ depressive symptoms shortly after they had reached mid-puberty (Angold et al., 1998). Thus, the relations among sex, age, pubertal development and children’s depressive symptoms are complex, and have not yet been studied in children of depressed parents. Family Conflict Levels of conflict are higher in families with a depressed parent (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Garber, 2005), and family discord is associated with depressive symptoms in children (Davies & Windle, 1997). Moreover, children of depressed parents also have been found to be particularly sensitive to stress (Bouma, Ormal, Verhulst, & Oldehinkel, 2008). Davies and Windle (1997) noted that high levels of conflict may mediate the relation between parent and child depression (Davies & Windle, 1997). It also is possible that family conflict acts as a moderator of this relation. That is, the relation between parent and child depression may be stronger in families with a depressed parent where there is more as compared to less conflict. In summary, sex, age, pubertal development, parental depression, and family conflict all have been shown to be associated with depression in children. The purpose of the present study was to examine the extent to which each of these variables further conditioned (i.e., moderated) the link between parent and child depression in a sample of high and low-risk families. We hypothesized that: (1) current depression (MDD) in parents would be related to children’s depressive symptoms; (2) girls of depressed parents would be more likely to have depressive symptoms than boys of depressed parents and than girls of non-depressed parents; (3) older children of depressed parents would display more depressive symptoms than younger children of depressed parents and older children of non-depressed parents; (4) more pubertally developed children of depressed parents would show more depressive symptoms than less pubertally developed children of depressed parents and more pubertally developed children of nondepressed parents; and (5) children in high-risk, high conflict families would show higher levels of depressive symptoms than children in high-risk, low conflict families and children in low-risk, high conflict families. Finally, we also explored the interactions among these variables. In particular, we investigated whether (1) high-risk older daughters and (2) high-risk daughters who were more pubertally developed, experience higher levels of depressive symptoms. Method Participants Participants were 227 parent-child dyads (one parent and one child per family). The “high-risk” group consisted of 129 families in which a parent (72.9% mothers) was receiving treatment for a current Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and scored 14 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17; Hamilton, 1967). Exclusion criteria included a lifetime diagnosis of any psychotic or paranoid disorder, organic brain syndrome, intellectual disability, bipolar I or II, current or primary diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorder, certain personality disorders (antisocial, borderline, schizotypal). The comparison “low-risk” group included 98 families with parents (79.4% mothers) who were lifetime-free of mood disorders, psychotic disorder, organic brain syndromes, or personality disorders, and during the child’s life were free of adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse/dependence, psychotherapy longer than two months or eight sessions, and psychotropic medication use. Child participants were between 7 and 17 years old (Mean = 12.53, SD = 2.33). Exclusion criteria included a developmental disability or significant chronic medical conditions. Among the depressed parents, if more than one child was eligible, the child closest to age 12 years old was recruited. For the non-depressed families, the enrolled child was the one who was most similar to an offspring of a depressed parent in terms of age, sex, and race. The overall sample of child participants was 54.6% female; 69.6% Caucasian, 21.6% African-American, 1% Asian, and 6.9% multi-racial. High- and low-risk children did not differ significantly in age, sex, or race. Procedure Participants were obtained from three cities in the southeast, northeast, and northwest United States. Depressed parents were recruited from clinics when they first presented for treatment. Recruitment of comparison families involved advertisements and coordination with local schools, health maintenance organizations, and community agencies. These parents were initially screened over the phone, and if eligible, then were scheduled for an evaluation to further assess eligibility criteria. High-risk children were assessed at the beginning of the parents’ treatment, by different evaluators than those assessing and treating the parent. Low-risk children were assessed within two weeks after the parent was found to be eligible for the study. Measures Parent Psychopathology. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) and Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II; First, Spitzer, Gibbons, Williams, & Benjamin, 1996) was used to assess current and past psychiatric disorders and personality disorders. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID has been found to be good (e.g., Zanarini et al., 2000). For this study, a randomly selected subset of taped interviews was used to assess inter-rater reliability yielding kappa coefficients >.80. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1967) is an interviewbased measure of the severity of depression during the previous week. The 17-item version yields scores ranging from 0 to 52; higher scores indicate greater severity. The HRSD has high inter-rater reliability (i.e., > .84). Intra-class correlation in this study was .96. Children’s Depressive Symptoms. The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) was used to measure children’s self-reported symptoms of depression. Each of the 27 items lists three statements in order of symptom severity. Total scores can range from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity have been well-documented for the CDI (Kovacs, 1992). In this sample, internal consistency was high (α =.84). Pubertal Development. The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988) is a self-report measure of children’s pubertal development. It consists of 5 items each coded on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more advanced development. The PDS contains gender-specific questions pertaining to signs of physical development, such as growth in height, skin changes, and body hair. It has been shown to have a high internal consistency (Petersen et al., 1988) and high criterion validity (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1987). Internal consistency for this sample was .87. Family Conflict. Children completed the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary). This 20-item, true-false measure of perceived parent-child conflict includes items such as “The talks we have are frustrating,” and “We almost never seem to agree.” The CBQ has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Robin & Foster, 1989). In the current sample, internal consistency was high (α = .87). Results Correlations among Study Variables Table 1 displays means and standard deviations for all study variables. Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Child age was significantly associated with family conflict, indicating that levels of parent-child conflict were higher for older child ages. Age also was significantly associated with pubertal development. Higher levels of depressive symptoms were significantly associated with more advanced pubertal development and greater family conflict. Data Analysis First, a linear regression analysis was conducted with risk as the independent variable and children’s depressive symptoms (i.e., CDI) as the dependent variable. Next, separate regression analyses were conducted for each potential moderator, with risk and the moderator (i.e., child sex, age, pubertal development, and family conflict) as independent variables, and CDI score as the dependent variable. All main effects and two-way interactions were tested. Next, two multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the three-way interactions of (a) risk, sex, and age, and (b) risk, sex, and pubertal development, on CDI scores. Simple slope analyses were conducted on all significant interactions (Aiken & West, 1991). Relation of Risk to Children’s Depressive Symptoms There was a significant main effect of risk on children’s depressive symptoms (β= 3.58; pr=.30, p<.001), such that high-risk was associated with significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms than low-risk. Does Sex Moderate the Relation between Risk and Children’s Depressive Symptoms? Regression analyses revealed a significant risk by sex interaction predicting depressive symptoms (β = -3.05; pr = -.13; p = .05). Simple slope analyses revealed that for girls, risk significantly predicted depressive symptoms (β = 4.99; pr = .30; p < .001), with high-risk girls reporting significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms than low-risk girls (see Figure 1). For boys, risk was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (β=1.94; pr=.11; p=.09). Within the high-risk group the difference between girls and boys showed a nonsignificant trend (β=-1.87; pr=-.12; p =.07); within the low risk group sex was not significantly related to depressive symptoms (β=1.19; pr=.07; p=.32). Does Age Moderate the Relation between Risk and Children’s Depressive Symptoms? The interaction of risk and age did not significantly predict children’s depressive symptoms (β=.31; pr=.06; p=.36). The main effect of age on depressive symptoms showed a nonsignificant trend (β=.30; pr=.12; p=.07) for older age to be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Does Pubertal Development Moderate the Relation between Risk and Children’s Depressive Symptoms? The interaction of risk and pubertal status significantly predicted children’s depressive symptoms (β= 2.16; pr=.17; p < .05). Simple slope analyses revealed that within the high-risk offspring group, more advanced pubertal development was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (β=1.86; pr=.23; p = .001). For low-risk children, extent of pubertal development was not significantly related to level of depressive symptoms (β=-.30; pr=-.03; p=.66). At both more advanced (β=.50; pr=.02; p=.75) and less advanced (β=-3.28; pr=-.08; p=.28) pubertal development, the relation between risk and children’s depressive symptoms was not significant (see Figure 2). Does Conflict Moderate the Relation between Risk and Children’s Depressive Symptoms? The risk by conflict interaction was significant (β=.34; pr=.14; p < .05). Simple slope analyses revealed that in families with high conflict, risk was significantly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (β=3.07; pr=.30; p < .001), whereas for low conflict families, risk was not significantly associated with children’s depressive symptoms (β = .32; pr = .02; p = .82) (see Figure 3). For both high (β=.96; pr= .57; p <.001) and low (β = .63; pr = .30; p < .001) risk children, conflict was significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Do the interactions between sex and age or between sex and pubertal development moderate the relation between risk and children’s depressive symptoms? Regression analyses revealed that neither the risk by sex by age interaction (β=-1.09; pr=.11; p=.11), nor the risk by sex by pubertal development interaction (β=-1.98; pr=.-08 ; p=.30) significantly predicted children’s depressive symptoms. Discussion The current study found several interesting relations among parental depression, children’s depressive symptoms, and children’s sex, age, pubertal development, and parent-child conflict. As expected, depressive disorder in parents was significantly associated with children’s depressive symptoms. In addition, sex, pubertal status, and conflict significantly moderated the relation between parental MDD and children’s depressive symptoms. Consistent with previous research (Cortes, Fleming, Catalano, & Brown, 2006; Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1995; Weissman et al., 1987), daughters of depressed parents reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than daughters of non-depressed parents. In contrast, no difference was found in levels of depressive symptoms for sons of depressed versus nondepressed parents. Interestingly, pubertal status significantly moderated the relation between risk and depressive symptoms, whereas age did not. Among high-risk youth, more advanced pubertal development was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. In contrast, for low-risk children, puberty was not significantly related to depressive symptoms. Thus, the combination of living with a depressed parent and experiencing the potential stressors associated with puberty may be particularly difficult, leading to higher rates of depressive symptoms. It is possible that the experience of pubertal development differs between high- and low-risk offspring. Depressed parents may react more negatively to advancing pubertal development. Also, depressed parents might be less available to support the teen during the normative challenges of puberty. Consistent with previous findings, (Davies & Windle, 1997; Garber, 2005) family conflict significantly moderated the relation between risk and depressive symptoms. Specifically, high-risk children in high conflict homes reported more depressive symptoms than high-risk children in low conflict homes or low-risk children in high conflict homes. Low-risk children in high conflict homes also reported more depressive symptoms than low-risk children in lowconflict homes. Thus, high family conflict was an important risk factor for depressive symptoms, regardless of parental depression; when combined with the risks associated with having a depressed parent (e.g., genetic vulnerability, maternal criticism), high family conflict may make high-risk children even more vulnerable to developing depression. The finding that high-risk children with less parent-child conflict had lower levels of depressive symptoms than those in high conflict homes, suggests that reducing conflict may be an important target for intervention. The interactions of neither sex and age nor sex and pubertal development moderated the relation between parent and child depressive symptoms. Several explanations for these findings are possible. First, these variables may not interact to predict child depression in a high-risk sample. For example, in children of depressed parents, the moderating effect of pubertal development may be the same for girls and for boys. Second, our measure of pubertal development may not have assessed aspects of pubertal development particularly relevant to risk for depressive symptoms. Pubertal timing and/or course may be better predictors of depressive symptoms than pubertal development alone (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Angold et al., 1998). The measure of pubertal development used here was a continuous measure based on one time point, and we were unable to assess timing of the onset of pubertal development. Finally, the relation between parental depression and child depressive symptoms may vary as a function of child sex, age, and pubertal development. It is possible that all four of these factors interact to form the most complete predictor of depressive symptoms in children. Given the sample size in the current study, however, we likely would not have had sufficient power to test this four way interaction. Limitations and Future Directions Limitations of this study highlight important directions for future research. First, data about children’s depressive symptoms, pubertal status, and parent-child conflict were based on self-report questionnaires completed by the children. As a result, relations among these measures could have been due, in part, to shared method variance. Given that the relations among these variables differed as a function of which particular moderator was being analyzed, however, it is not clear why “rater bias” would affect some of these relations more than others. Moreover, the measures of the most important relation in this study – between parents’ MDD and children’s depressive symptoms – were based on different informants (i.e., parents and children, respectively). Nevertheless, whenever possible, multiple methods and measures (e.g., parent report; behavioral observation) of the constructs being studied should be used. Second, the current study was cross-sectional, and therefore the direction of the relations among the variables cannot be determined from these data. Parent and child depression can reciprocally influence each other (Ge et al., 1995; Kouros & Garber, 2010). For example, the relation between conflict and depressive symptoms in high-risk youth could have been due as much to the child’s depression leading to the parent-child conflict as to the reverse (i.e., conflict leading to depression in the youth). Moreover, the relation between parents’ and children’s depression also could have been due to some third variable (e.g., genes, common stressors) not assessed here. Prospective studies are needed to better understand the temporal relation between risk and children’s depressive symptoms and the contribution of these moderators to this relation across time. Third, the relations among parent depression, child depression, and child sex may differ as a function of parents’ sex (Hops, 1992; Luthar, Cushing, & McMahon, 1997). For example, children of depressed mothers have been found to have higher levels of internalizing problems than children of depressed fathers (Connell & Goodman, 2002). Given the small number of depressed and nondepressed fathers in the current study, we likely would not have had sufficient power to adequately test parent sex as another possible moderator. Finally, the current study explored a variety of potential moderators separately. However, these variables do not operate in isolation. Future research should examine how they are related to each other, as well as which ones best explain the intergenerational transmission of depression from parents to their children. Overall, the present study identified several moderators of the relation between parental MDD and children’s depressive symptoms. Some of these moderators may be appropriate targets for prevention. As has been reported in community samples (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998), girls in high-risk families may be particularly at risk for developing depressive symptoms. As such, daughters of depressed parents may be especially important targets of intervention. More advanced pubertal development also was significantly related to higher levels of depressive symptoms for high-risk youth. Targeting youth based on extent of pubertal development rather than age, per se, might be a better strategy for identifying those at greatest risk. Interventions aimed at addressing the specific challenges that accompany puberty (e.g. managing hormonal changes, understanding body development) could be particularly beneficial. Finally, interventions focused on reducing the level of parent-child conflict in high-risk families may prevent children from developing depressive symptoms or may lessen current symptoms. Future research should examine the effectiveness of targeting these different variables for preventing depression in high risk youth in particular. References Aiken, L.S. & West, S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington DC: Author. Angold, A., Costello, E.J., & Worthman, C.M. (1998). Puberty and depression: The roles of age, pubertal status, and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine, 28, 51-61. doi: 10.1017/S003329179700593X Beardslee, W.R., Versage, E.M., & Gladstone, T.R.G. (1998). Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1134-1141. Billings, A.G., & Moos, R.H. (1985). Life stressors and social resources affect posttreatment outcomes among depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 140-153. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.94.2.140 Bouma, E.M.C., Ormel, J., Verhulst, F.C., & Oldehinkel, A.J. (2007). Stressful life events and depressive problems in early adolescent boys and girls: The influence of parental depression, temperament, and family environment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105, 185-193. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.007 Brennan, P.A., LeBrocque, R., & Hammen, C. (2003). Maternal depression, parent-child relationships, and resilient outcomes in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1469-1477. Brooks-Gunn, J., Warren, M. P., Rosso, J., and Gargiulo, J. (1987). Validity of self-report measures of girls' pubertal status. Child Development, 58, 829-841. Connell, A.M. & Goodman, S.H. (2002). The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A metaanalysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 746-773. Cortes, R.C., Fleming, C.B., Catalano, R.F., & Brown, E.C. (2006). Gender differences in the association between maternal depressed mood and child depressive phenomena from grade 3 through grade 10. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 815-826. Cummings, E.M. & Davies, P. (1994). Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 73-112. Cyranowski, J.M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, K. (2000). Adolescent onset of the gender difference in major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 21-27. Davies, P.T. & Windle, M. (1997). Gender-specific pathways between maternal depressive symptoms, family discord, and adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 33, 657-668. Downey, G. & Coyne, J.C. (1994). Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 50-76. Fergusson, D.M., Horwood, L.J., & Lynskey, M.T. (1995). Maternal depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36, 1161-1178. First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbons, M., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. (1996). User's guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II): New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J.B.W. (1997). User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Garber, J. (2005). Depression and the family. In Hudson, J.L. & Rapee, R.M. (Eds.), Psychology and the family (pp. 225-280). New York, NY: Elsevier Science. Ge, X., Conger, R.D., & Elder, G.H., Jr. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 37, 404-417. Ge, X., Lorenz, F.O., Conger, R.D., Elder, G.H., & Simons, R.L. (1994). Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 30, 467-483. Goodman, S.H. and Gotlib, I.H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106, 458-490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458 Gore, S., Aseltine, R.H., & Colten, M.E. (1993). Gender, social-relational involvement, and depression. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 3, 101-125. Hamilton, M. (1967). Development of a Rating Scale for Primary Depressive Illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 6, 278-296. Hammen, C. & Brennan, P.A. (2003). Severity, chronicity, and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 253-258. Hankin, B.L. & Abramson, L.Y. (1999). Development of gender differences in depression: Description and possible explanations. Annals of Medicine, 31, 372-379. Hankin, B.L., Abramson, L.Y., Moffitt, T.E., Silva, P.A., McGee, R., & Angell, K.E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 128140. Hankin, B.L. & Abramson, L.Y. (2002). Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity, and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 31, 491-504. Hops, H., Sherman, L., & Biglan, A. (1990). Maternal depression, marital discord, and children's behavior: A developmental perspective. In G. R. Patterson (Ed.), Depression and aggression in family interactions (pp.185-208). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Hops, H. (1992). Parental depression and child behavior problems: Implications for behavioral family intervention. Behavior Change, 9, 126 – 138. Hops, H. (1996) Intergenerational transmission of depressive symptoms: Gender and developmental considerations. In: Mundt, C., Goldstein, M.J. (Eds) Interpersonal factors in the origin and course of affective disorders (pp 113–129). Gaskell/Royal College of Psychiatrists, London Kashani, J.H., Cantwell, D.P., Shekim, W.O., & Reid, J.C. (1982). Major depressive disorder in children admitted to an inpatient community mental health center. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 671-672. Kovacs, M. (1992). Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. Ontario, Canada: MultiHealth Systems. Lieb, R., Isensee, B., Höfler, M., & Wittchen, H.U. (2002). Parental depression and depression in offspring: Evidence for familial characteristics and subtypes? Journal of Psychiatric Research, 36, 237-246. Luthar, S., Cushing, G., & McMahon, T. (1997). Interdisciplinary interface: Developmental principles brought to substance abuse research. In S. Luthar & J. Burack (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder (pp. 437–456). New York: Cambridge University Press. Mendle, J., Harden, K.P., Brooks-Gunn, J., Graber, J.A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1341-1353. Petersen, A.C., Crockett, L., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 117133. Prinz, R.J., Foster, S., Kent, R.N., & O’Leary, K.D. (1979). Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 12, 691-700. Restifo, K., Akse, J., Guzman, N.V., Benjamins, C., & Dick, K. (2009). A pilot study of self- esteem as a mediator between family factors and depressive symptoms in young adult university students. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197, 166-171. Robin, A. L., & Foster, S. L. (1989). Negotiating parent–adolescent conflict: A behavioral– family systems approach. New York: Guilford Press. Rudolf, K.D. & Hammen, C. (1999). Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development, 70, 660-677. Rutter, M.L. (1986) Child psychiatry: The interface between clinical and developmental research. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences, 16, 151-169. Weissman, M.M., Gammon, G.D., John, K., Merikangas, K.R., et al. (1987). Children of depressed parents: Increased psychopathology and early onset of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 847-853. Zanarini, M.C., Skodol, A.E., Bender, D., Dolan, R., Sanislow, C., Schaefer, E., et al. (2000). The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagonoses. Journal of Personality Disorders, 14(4), 291-299. Table 1. Means and standard deviations for the study variables Total Low Risk Mean (SD) 12.72 (2.22) Girls Boys Mean (SD) 12.53 (2.33) High Risk Mean (SD) 12.38 (2.40) Mean (SD) 12.64 (2.42) Mean (SD) 12.44 (2.24) Pubertal Development 2.41 (0.87) 2.35 (.89) 2.48 (.85) 2.16 (.76) 2.62 (.91) Conflict 3.45 (4.08) 3.90 (4.39) 2.86 (3.56) 3.00 (3.60) 3.83 (4.41) Depressive Symptoms 6.56 (6.03) 8.10 (6.66) 4.52 (4.32) 6.30 (4.9) 6.79 (6.86) Variable Age Table 2. Correlations among study variables Risk Sex Age Pubertal Development Conflict Risk -- Sex .014 -- Age -.073 .043 -- Pubertal Development Conflict -.071 -.264*** .728*** -- .126~ -.102 .174** .216* -- CDI .295*** -.040 .036 .129~ .600*** ~p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01, *** p < .001 CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory CDI -- Figure 1. Risk by Sex interaction predicting depressive symptoms (CDI Scores) 16 14 Boys Girls CDI Score 12 *** 10 8 6 4 2 0 High Risk ***p < .001 Low Risk Figure 2. Risk by pubertal development interaction predicting depressive symptoms (CDI Scores) 16 14 More Pubertally Developed CDI Score 12 Less Pubertally Developed *** 10 8 6 4 2 0 High Risk ***p < .001 Low Risk Figure 3. Risk by Conflict interaction predicting depressive symptoms (CDI Scores) 16 High Conflict 14 CDI Score 12 Low Conflict *** *** 10 8 6 *** 4 2 0 High Risk ***p < .001 Low Risk