Awayday2015_breakout..

advertisement

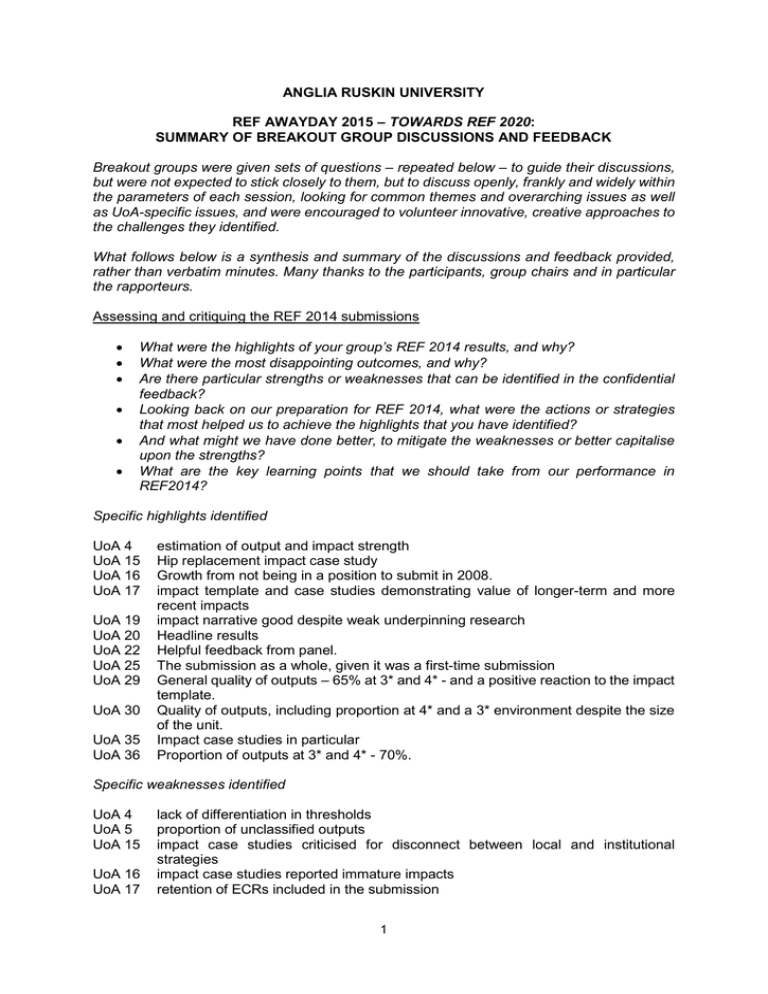

ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY REF AWAYDAY 2015 – TOWARDS REF 2020: SUMMARY OF BREAKOUT GROUP DISCUSSIONS AND FEEDBACK Breakout groups were given sets of questions – repeated below – to guide their discussions, but were not expected to stick closely to them, but to discuss openly, frankly and widely within the parameters of each session, looking for common themes and overarching issues as well as UoA-specific issues, and were encouraged to volunteer innovative, creative approaches to the challenges they identified. What follows below is a synthesis and summary of the discussions and feedback provided, rather than verbatim minutes. Many thanks to the participants, group chairs and in particular the rapporteurs. Assessing and critiquing the REF 2014 submissions What were the highlights of your group’s REF 2014 results, and why? What were the most disappointing outcomes, and why? Are there particular strengths or weaknesses that can be identified in the confidential feedback? Looking back on our preparation for REF 2014, what were the actions or strategies that most helped us to achieve the highlights that you have identified? And what might we have done better, to mitigate the weaknesses or better capitalise upon the strengths? What are the key learning points that we should take from our performance in REF2014? Specific highlights identified UoA 4 UoA 15 UoA 16 UoA 17 UoA 19 UoA 20 UoA 22 UoA 25 UoA 29 UoA 30 UoA 35 UoA 36 estimation of output and impact strength Hip replacement impact case study Growth from not being in a position to submit in 2008. impact template and case studies demonstrating value of longer-term and more recent impacts impact narrative good despite weak underpinning research Headline results Helpful feedback from panel. The submission as a whole, given it was a first-time submission General quality of outputs – 65% at 3* and 4* - and a positive reaction to the impact template. Quality of outputs, including proportion at 4* and a 3* environment despite the size of the unit. Impact case studies in particular Proportion of outputs at 3* and 4* - 70%. Specific weaknesses identified UoA 4 UoA 5 UoA 15 UoA 16 UoA 17 lack of differentiation in thresholds proportion of unclassified outputs impact case studies criticised for disconnect between local and institutional strategies impact case studies reported immature impacts retention of ECRs included in the submission 1 UoA 19 UoA 20 UoA 22 UoA 25 UoA 29 UoA 30 UoA 35 UoA 36 outputs not as highly ranked as anticipated Ranking of outputs uneven and guesswork about what went best. Rising expectations and standards a problem. with hindsight, impacts was not as effectively dealt with as it might have been disconnect between ‘mock’ and actual assessments of quality; the unit had done even worse than predicted. the 10% of outputs rated at 1* that dragged things down; poorer research environment rating. that one impact case study failed, and the fact that the impacts submitted didn’t reflect the public profile of the department. The number of 1* or unclassified outputs, and also issues around handling practicebased outputs. The impact template – it was too generic and did not include enough about future plans. Leading submission development The Convenor and Co / Deputy Convenor roles were crucial, and need to be filled by individuals capable of, and supported by their HoDs and Deans to give, strong leadership. Convenors must not be left isolated. Getting the engagement of non-research-active HoDs was felt to be particularly challenging Ensuring that each Convenor had the support of a Co or Deputy Convenor who attended the same events and training, etc, and was therefore able to both effectively support and take over from the Convenor as necessary was essential for sustainability and continuity. Convenors need to be allowed more time dedicated to meeting this aspect of their roles. It is also essential to understand that the role of Departmental Research Convenor is distinct from that of a UoA Convenor: clarity of role is key. REF preparations needed team ownership, leadership and management to support the Convenors, from individual researchers all the way up to CMT and the most senior management. There needed to be better integration of process, policy and task at all levels. It was unanimously agreed that too much had happened too late last time round, which had meant that there had not been sufficient time and space to reflect on what was being proposed in some cases, leading to decisions that might have been taken differently; and in any case had consequences in other areas that could have been resolved more effectively with more time. This was particularly the case with UoA 23 – it had been right to try and develop a distinct submission and then right to decide that it wouldn’t work, to strip its assets and put them in other submissions, but the decision had been made too late to ensure the maximum benefit. Convenors must be given a clear period of time (two weeks at least) ahead of final submission to ensure they have the time and space to make the final changes required of them. There was also a concern that Faculty resources had been brought to bear really only at the last sprint for the line, rather than over a more sustained period. There had perhaps also been too much attention given to drafting and re-drafting the paperwork than on achieving the best possible outputs and impacts. There were concerns that there had been too much institutional interference in the paperwork, often very last minute, which had not necessarily helped. We are already nearly two years into the assessment period for the next REF and there was a feeling in certain quarters, especially in relation to ‘new’ UoAs, that this represented a lost period of time for planning and preparation. A more effective steer was needed from higher management to make the next REF a management as well as a personal target. 2 Planning needs to take place at the level of individuals, UoAs, and cross-departmental themes. It was noted that some institutions, especially in Health areas, had made great use of employing clinical staff on a fractional basis – submission sizes in certain institutions were over-inflated by comparison with reality. But this strategy had been of benefit, and it was something we should not be averse to, including in other areas. But it had to be planned for. Setting a quality threshold It was felt that aiming for a higher threshold than the 2* expectation set by the institution, enabling a leaner submission, might have been of benefit. This would suggest a need for variable thresholds in the next REF exercise, taking into account the actual position and strength of individual units. What might make up suitable benchmarks? There was also discussion about making the threshold based on an average quality score rather than being an absolute threshold – although this was possible in REF 2014 it was only so in exceptional cases. Would we have been able to submit more colleagues if we had accepted three strong and one weaker output and would this have had beneficial consequences? There were concerns that some submissions had been too small and had therefore been penalised, so submitting more colleagues at the expense of average quality might have actually worked in our favour. It was felt that the 2* threshold had actually had negative consequences because it was rather general. Those people most capable of producing the highest quality of research had not felt stretched to achieve it (2* was ‘too easy’). However, might removing the ‘long tail’ that the 2* threshold allowed in some UoAs, have negative consequences? Rating the quality of work Estimating the strength / quality of outputs and impact was felt to have been effective in some areas, but our (internal/external) assessment of outputs did not match the result in others. They were usually overly optimistic. It is important to establish the nature of work that will score well – and where the evidence comes from that informs our strategy and why we should trust it. Decisions were taken to avoid certain kinds of work, for example, that seemed unjustified in hindsight, when the REF results and other institutions’ submissions in which such work had been included, became available. Dealing with practice as research had been tricky and we needed to do more work to get this right in future. It was also important to choose the UoA wisely – the same research could have better quality outcomes depending on the UoA it was submitted to. External reviewers had been helpful, but in some cases they had often been selected very late, leading to concerns that they were perhaps the ‘leftovers’ from the sector, and because it could become, particularly towards the closing stages of our preparations a very transactional relationship, there were also concerns about the rigour of the feedback received. For example, in some cases a clear steer was given that qualitative work would do more poorly than quantitative work, which proved unjustified by the end results. It was felt that having a more sustained relationship and longer-term engagement with external reviewers would be helpful. 3 It was also felt sometimes that reviewers had been asked, or had been prepared to comment on, work that fell outside their main area of expertise; advice on sub-specialisms was essential but if it was unreliable, it was not helpful. We should not be averse to having a large number of reviewers reviewing only small numbers of outputs in future, and as a matter of good practice every item reviewed should be looked at by at least two reviewers. There was also a variety of practice in how reviewers reported, and there should certainly be some uniformity, at least at the level of the submitting unit, but preferably across the board. It was felt also that where multiple reviewers were involved, it would be helpful to bring them together to form a panel to discuss their ratings and agree on a common score, achieving a much more integrated process. There were concerns that the process for the selection of external reviewers had been ineffective and a different approach was needed in future. Ideally reviewers should not be personally known to the submitting department, and they should have a background of REF or RAE panel membership or having been part of a strong submission. [Editor’s note: for REF 2014, external reviewers were expected to have been an RAE 2001 or 2008 panel member, or to have led an RAE 2008 submission attaining at least 2*. UoA Convenors nominated candidates meeting these criteria who were approved by the Deputy Vice Chancellor for Research. In exceptional cases, these criteria were relaxed to enable the appointment of individuals with specific subject specialisms]. Reviewers could also have had a wider brief – they had typically been asked only to comment on outputs. Certainly, we need to ensure we are making the best use of reviewers. There was some suggestion that we should be capable of effective quality review internally, and the best support external reviewers might have provided was around the narrative statements. Developing impact case studies Understanding what impact was, was a major issue. It is still a problem. More needs to be done to provide effective training and development in respect of impact. Every research project should have an impact strategy, whether the funder requires it or not. Impacts work best, or so it seems, when there is a good connection between the research and end users who can benefit from or implement it. Impact has to start with the research, rather than being added on later. Research results need better dissemination. We need to improve the ‘follow through’ from research projects to help generate impact. We need to allow time at the end of research projects, including keeping research staff on, to ensure that impact activities can be put in train and the research findings effectively written up and disseminated. Case studies representing a quick process from research to impact could be effective, but need to be carefully targeted to have good results. We need to be careful about where the underpinning research was done – the actual research, not just development of impact from it, needs to happen at the current institution. It was also crucial to ensure that impacts being claimed did not come out of the work of doctoral students, unless staff had a clear role in those projects. Impacts based on a long history of research seemed to work best. A key concern around the impact case studies had been around collecting the relevant evidence to corroborate the case studies. It was essential to ensure that all colleagues were aware of the importance of doing so, to facilitate the impact trail which would be crucial to the drafting of case studies for the next REF. It was also important to ensure that impact case studies were being identified and developed for the next REF. In doing this, and recognising that some colleagues are not keen on impact 4 or their work is not best suited to achieving impact, one strategy that might be worth considering would be to identify a small number of individuals who were seen to be a ‘good bet’ for producing impact for the next REF. It was noted that some institutions had brought in professional assistance, or support from other universities, to help write impact case studies, and that this was reportedly effective, and it was suggested that this should be considered for REF 2020. We could also have been more cunning – could the same case study have been submitted in more than one unit of assessment? It may actually be a useful strategy to get smaller UoAs to work together collaboratively to achieve this, though there was a danger that the case study would be scored differently depending on the UoA to which it was submitted. Supporting the research environment We still have a culture which is dominated by teaching rather than research, and this colours how research is approached and supported. Deans need to ensure research is an ongoing priority and be less risk-averse in supporting it. Institutional strategies need to be more joined up with research and at more local levels. Every process needs reflect and to help embed research culture. Policies have to be clear. It was noted that the research environment covered not only submitted staff, but their colleagues as well and there would be activities that they engaged in that would contribute to the research environment and could usefully be advanced as evidence. This applied equally to impact. There were concerns about the quantity of research income and doctoral awards claimed. Clearly dealing with the root cause – raising income generation and timely completion – was essential, but it was also critical to ensure that data about income generated and awards made was properly coded to ensure that it could be claimed in the next REF, as HESA data is relied upon and is finalised each October following the financial year end in July. There was a sense that research income had been raised in spite of, rather than because of, institutional support. Questions were raised about the division of research income data and doctoral completions. For many UoAs in REF 2014 this had been what it would be, but it was noted that the submission to UoA 3 had done very well because it had been able to include a lot of activity relating to Health research. If submissions were to be made in future in additional Health areas, what would the consequence of this be? It was noted that outside collaboration had been positively commented upon, as was having a lively academic environment – having an early career researcher plan was seen to have helped. Finally it was noted that the environment statements had been quite structural – i.e. they had explained details relating to seminars, support for PhD students, etc – and more holistic than in RAE 2008. While such information was requested, it might be better to take an approach that e.g. “QR income has been used to support A, B, C, D and E” as this would enable more of a narrative. This might also help deal with concerns that statements had been too bland, or too centralised, and had worked as ‘boilerplate’ text without allowing for the identity of the submitting unit to come through effectively. There was perhaps also a lack of institutional ambition, which was reflected in the narrative statements. 5 Ensuring effective recognition A mixed reaction from the university was notable when the results were published. UoAs that did not achieve any 4* rating were made to feel second-class, which seemed unfair, particularly where it was the first time such a submission had been made. How do we enable a good REF submission next time? 1. Identifying and supporting returnable staff What are the strengths and weaknesses in our current ‘complement’ of staff? What strategies should we adopt to address any perceived weaknesses? Do we provide appropriate levels of support for returnable staff, especially ECRs, and what might we do better? Were our processes for selecting staff for REF2014 appropriate and satisfactory? Were our processes for recognising and dealing with individual staff circumstances appropriate and satisfactory? Importance of having a strategy What do we want to achieve / what do we aspire to? This is crucial to setting a strategy. Three potential strategies – aim to submit everyone (or, at least, aim to maximise everyone’s ability to be submitted); aim to consolidate and grow existing strengths; or aim to control the research focus into a more concentrated submission. Do you define the latter two in terms of themes, or groups? An inclusive approach had been taken for REF 2014, but it was not clear whether it should be continued. Going forward with the culture of everyone being submitted to the REF – which was the strategy for UoA 29 towards REF 2014, although it was ultimately unsuccessful – may have future benefits around submission size. Cohesion and sustainability are key. Once a strategy has been identified, this needs to be made clear to the submitting group repeatedly. Understanding what went right and what went wrong in the REF 2014 submission, sharing the Awayday discussions for example, would be helpful in making this a joint effort. The staffing strategy, both broadly and in its specific components, needs to support, rather than impact negatively upon, the environment narrative. Identifying strengths and weaknesses and selecting staff for submission It is difficult to know who might be able to be submitted – not easy within a department, but there’s also the need to understand who in the department can contribute to other UoAs, and who outside the department can usefully be brought in to the submission. Individuals need to (be helped to) develop and understand a ‘selection time line’ identifying what they need to do be submittable and by when, aligning plans with the REF publishing cycle. These objectives and research plans need to be followed up on though. This is a key part of the appraisal process – or should be. 6 Like the submitting unit as a whole, individuals also need a strategy in terms of whether to consolidate existing areas of research strength or to develop new ones. There is however a danger in being too strategic – we need both quality and quantity to compete effectively. Colleagues were ‘left behind’ by the 2* threshold, or by the ‘fit’ of their research in REF 2014, and it is important to ensure that when this does happen, those who are affected continue to be encouraged and supported. A number of colleagues perceived to be working at high level were left out of REF 2014 submissions, but it was not clear why, creating dissatisfaction. Ensuring that colleagues declare any mitigating circumstances is essential, but could often be (for perfectly good reasons) difficult to achieve. Supporting researchers Appropriate staff support starts with appropriate appointments to roles within departments, and enabling those role-holders to provide the support through giving sufficient credit / relief through AWBM. (This also applies more generally to ensuring the trade-off between teaching and research is given sufficient attention). Everyone feels they are time-poor; a very quick way to get more research done would be simply to appoint more people, so the non-research load is better spread. REF5 statements made claims about what the university was doing or would do to support Early Career Researchers – in particular that they are given additional time to research. It is crucial to have HoD support to ensure this is put into place. Similarly, if other claims about support more generally were made, this need to be implemented. What is actually needed must be disseminated down to appraisers / course group (deputy head) level, as this is where decisions about time allocation are made. What about the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers? This needs to be implemented. [Editor’s note: it has been, and has been recognised by the award of the HR Excellence in Research Award. The fact that this is not simply known about is, however, an issue we need to be addressed, as well as to ensure that we retain the HR Excellence in Research Award, due for renewal in spring 2017]. There were concerns about the level of support available at an institutional level, including in RDCS, for supporting research and researchers – colleagues are doing their best, but the perception is that the valuable role played by Caroline Strange has been allowed to lapse. We should consider teaching-only posts, allowing colleagues to play to their strengths and follow their interests, while at the same time freeing other colleagues up to spend more of their time on research. Ensuring we also use teaching cleverly is important – ECRs in particular need better support to help understand what they can and can’t do or change in relation to the modules they teaching, and how to feed their research into their teaching. We can also be more creative about module choice and options for newly appointed staff. Some UoAs have already lost staff – retaining as many as we can is critical. A key reality in our institution is that researchers are isolated, and anecdotal evidence suggests that wanting to have colleagues working in the same area is a key reason for moving. 7 Recruitment processes All appointments need to be made in line with the strategy of the relevant UoA. We need to ensure we consider an individual’s research track record when appointing to posts that involve research, including where appropriate, administration of research. Recruitment panels need to include existing researchers to enable this. UoA Convenors should be involved in all appointments to help determine how potential appointees can be best integrated into the unit’s research strategy. It is useful for newly-appointed staff to have some sense of the expectations surrounding the REF, but there are very few guidelines to give to such colleagues about this. It is essential that newly-appointed staff come into an environment that is positive and energising. 2. Producing quality outputs What more can we do to help produce 3* and 4* outputs, and in the appropriate number? How do we best assess the quality of our outputs, and how should be best use external reviewers? What should we do in terms of ‘mock REF’ or ‘stock taking’ processes? Are the open access requirements of the next REF sufficiently understood, are they being appropriately applied, and what else can we do to ensure compliance? Producing and identifying good quality outputs First and foremost, we need to know what we are producing. We need an integrated approach to the ongoing monitoring of research activity, ensuring that systems are streamlined so that researchers are not asked repeatedly for the same data; perhaps this could be linked to ARRO. We need to develop a better understanding of what the different REF star ratings mean – can we identify exemplar papers that we think are 4*, 3*, 2* etc. (This will be different in different UoAs). In particular, understanding what is 1* so that it can be avoided is crucial. We should make better use of some elements of the REF e.g. the rules around double-weighting. Perhaps all monographs should simply be double-weighted, but we need to develop our understanding to ensure that we get these decisions right. Notwithstanding the value of external reviewers, we need to be able to place much more confidence in internal review processes. It is probably impractical to arrange anonymous internal review, but collaborative review panels might prove acceptable. We need to work more collaboratively, both within departments and Faculties and across them, to ensure we challenge and stretch one another to encourage the production of the highest quality research. This will allow us to capitalise on good individual projects and develop critical mass, integrating across the UoA. We need to be more interdisciplinary, and there may be some value in strategically intervening to move people between groups, to achieve this. We also need to be wiser about cross-referring outputs between UoAs – there was a sense we did not do this enough. 8 Staff need better advice about where to publish – are there particular journals we should target to maximise the chances of a higher quality rating? This could be part of a research mentoring scheme teaming experienced and inexperienced researchers. In order to achieve 3* and 4* quality, research needs to be given a good run up via effective workload planning and deployment of QR funds. This could be done through secondment and fellowship schemes which are already in place in some departments. Resources are always an issue, but it was noted that there appeared to be a correlation between the best outputs and the busiest staff. Was it as much as matter of creating an atmosphere of enthusiasm than anything else? We can also buy in good quality outputs, and should not be averse to doing so. This means ensuring that recruitment decisions take account of a researcher’s publication record. Achieving open access We need to find ways to motivate people to use ARRO to ensure their work meets REF open access requirements. It will not work if responsibility is devolved to individual academics. Two solutions were proposed, either drop box or an equivalent directed to central admin, or an online front end to ARRO. [Editor’s note: it is not clear what the online front end to ARRO might be, as it already has one!]. 3. Developing impact Who ‘owns’ the REF3a strategies? Who is responsible for measuring and reporting the progress that has been made against them? What else needs to be happening to ensure we are delivering our impact strategies? How can we best generate, identify and select excellent impact case studies? What progress has been made already and is this sufficient? If not what more can be done? What additional systems do we need to capture and record the relevant evidence of impact? What more can we do to enable impacts to be generated from our research? Managing / supporting the REF3a strategies Convenors, in association with their HoD and Deputy Dean for / Director of Research have a crucial role to play in ensuring that their REF3a strategies are implemented, and linked up effectively with Faculty and institutional-level strategies. A budget is crucial – and if the REF3a does not show how funds and resources are to be made available to researchers for the support of impact, a strategy doing this must be developed. Delivering impact First and foremost we must understand impact better, in order to deliver it better. RDCS has some training activities under development which should be better advertised, and there might be a call for a specific REF impact workshop. 9 A crucial step is resource – impact must become a part of grant bids, where permitted; and where it is not, we should still be insisting on impact plans, setting out actions and resourcing requirements, to accompany any bids. Engaging with HoDs to ensure that this becomes a monitored, reported action is key. For researchers whose funding does not extend to impact, an institutional fund to which researchers can apply – making a good case in doing so of course – should be set up. We need to get much better at ‘outward facingness’ e.g. conferences, networking, engaging visiting speakers and other researchers. Working with research users we need to ensure we routinely capture their needs, feedback and other relevant data – both to evidence impact and to guide us forward. An audit trail, allowing and facilitating the collection of impact evidence, needs to be built into the design of the research. We must also avoid relying too heavily on one or a few members of staff. If we lose them, this can really cause difficulties around impact. Getting good case studies for the next REF The key thing is to identify impacts – with clear evidence of change or engagement. There should be a Faculty audit process to look at research carried out over the past ten years and to track its impact, and to identify the case studies to take forward. There is a balance to be struck between identifying and submitting existing impacts, and developing new impacts. In many ways it’s probably already very late in the day to be thinking about developing new impacts, as they are unlikely to be sufficiently mature in time for the next REF to score well. We might be able to submit developed versions of impact case studies submitted to REF 2014, so long as there is something distinct and different by comparison, but we cannot rely on this being the case until we have the REF rules and regulations. Once we have case studies developed, we should put together a business plan to develop them ready for submission. This might take the form of setting up something like the Department of Engineering and the Built Environment’s Advanced Practice Office. It will be very useful to share best practice among UoAs, which means giving time to enable convenors to do this. Even enabling the circulation of draft material would be of benefit. Colleagues need to get over their embarrassment at seeing impact case studies as blowing their own trumpet. It was worth noting that (on average) a single case study was worth the equivalent of 13 research outputs, in terms of the score. This was a clear reason to ensure sufficient time was spent in developing it. Other comments The ARU website needs serious work. It is not fit to support any aspect of research or internal administration and management. It is not at all easy to find details of colleagues or their activities. Is there any evidence that any of it is fit for purpose? The website is a crucial tool 10 for the dissemination of our research – for example, it can be used to provide statistics for web downloads. 4. Developing the research environment Who ‘owns’ the REF5 strategies? Who is responsible for measuring and reporting the progress that has been made against them? What else needs to be happening to ensure we are delivering our impact strategies? What more needs to be done to generate, capture and store evidence relating to the research environment? What can be done to develop collaboration externally and internally? Where are we with PGR supervision and completion, and support? Where are we with income generation and grant capture? Managing / supporting the REF5 strategies REF convenors, in association with their HoD who has access to relevant data, must take charge. For some UoAs, the HoD as budget-holder is best placed to lead on this. Without the involvement of the HoD, this becomes very difficult for the Convenor who has no control. Staff tend to be resistant to change when they are already under-resourced. There were however concerns that it is at the next level up (Faculty?) where there is more of an issue, as departmental-level colleagues are less able to shape Faculty support, despite having to be responsible for reporting on them in a REF submission, e.g. committee structures. Using QR funds effectively We should bear in mind that some UoAs, and therefore the QR funds that they earned, were cross-Faculty undertakings. In these cases, dividing the QR funding by Faculty may lead to such cross-Faculty areas being under-supported, and efforts should be made to avoid this. QR funding should be allocated to UoAs, and plans for the use of QR funds should be prepared at UoA level rather than Faculty level. A clear link between how QR funds, and sabbaticals, have led to specific REF outputs and impacts needs to be made, as this can help us understand how best to deploy QR funding in future. We should have clear and transparent strategies in place that explain how QR income, HEIF income, and the Research Enhancement Fund are deployed across the institution. Enabling and supporting (research) staff Strategies and policies around staffing, supporting postgraduate research students and early career researchers was always a critical part of the environment statement. Key issues that make for a good research environment revolve around teaching load, sabbatical opportunities, research travel budget; research seminar series. It is essential to get the basics right, for example, grievances around allocation of working space have derailed or detracted from conversations around enabling and supporting research; research meetings become resourcing meetings. 11 Even small amounts of money can really help, such as the modest sums that have enabled writing retreats at a departmental level. We may already have this kind of thing in place, but need to do more to better promote them so staff are aware. Initiatives that work well in one area can be replicated elsewhere. There were concerns about the lack of strategy / policy to ensure the sustainability of research. All too often projects came to an end without there being bridging arrangements in place to help ensure we retain the staff we have supported. Researchers’ careers need to be better supported, and reflected in the environment statements. We can use QR funds to allow ECRs in particular to run conferences and develop networks – this is gives a good grounding for their work. Periods of research leave are crucial. Mentoring needs to be embedded at all levels and in a variety of contexts e.g. research mentoring for ECRs; teaching mentoring for ECRs; mentoring for people taking research leave; mentoring for new staff, etc. Enabling and supporting doctoral students We need a careful recruitment policy, including specific advertisements, to attract the best PhD students. PhD students are also critical to retaining staff. We should be using QR money to appoint PhD students now, and to ensure that they complete in time for inclusion in the next REF. PhD students need to be better engaged in the day-to-day life of their departments. They also need to be encouraged to take an active part in this, which can be challenging when large proportions are not locally-based, including overseas. Even those locally-based do not necessarily participate as we would wish – one area asked its doctoral students to nominate a rep and did not receive a single response from 70+ students. It is difficult to create a community in these circumstances. (This is not the case across the board – another UoA in the same Faculty reported exactly the opposite.) One initiative that is being trialled is using QR money to appoint a paid postgraduate student coordinator to work 7 hours a week over 44 weeks, who will be expected to kick start the community; this has also been achieved via a fee waiver scheme. An issue with employing people (whether in this kind of student facing role, or in temporary postdoc / research assistant roles) is the expectation that temporary posts must all go through the Employment Bureau, and this is holding the appointments up. 12