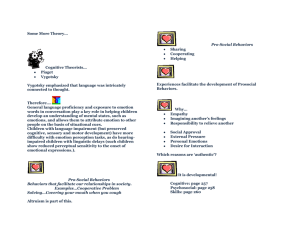

Prosocial development and morality

advertisement

Prosociality & Morality Daniel Messinger, Ph.D. 1 Prosocial Development 6/30/2016 Messinger 2 Through interaction, infants come to understand themselves as social beings who affect and are affected by others psy.miami.edu/faculty/dmessinger/ Proposed mechanism Young infants who act with the developing expectation of eliciting positive affect in the parent develop to be young children who regulate themselves to please their parents. 4 Morality is implicitly interactive Acting with respect to the expectations of a generalized other—norms—expecting one’s actions to affect others. 5 Early mother-infant synchrony 2 year self-control Maternal synchronization at 3 months – Faster is better Mutual synchronization at 9 months – More important for difficult temperament kids • Feldman et al 1999 Mother-infant synchrony dialogical empathy at 6/13 years Feldman, 2007 7 “Participating in a synchronous exchange may sensitize infants to the emotional resonance and empathy underlying human relationships across the life span.” Feldman, 2007 9 Empathic Responding Add video here Cooperation Add video here Empathy Autism Symptoms Effortful control, “Essentially, a child's ability to inhibit a readily available, prepotent response or to stop an ongoing response to perform instead a more appropriately modulated response is implicated in multiple developmental processes and considered a hallmark in socialization.” – Typically viewed as a temperamental characteristic – Murray & Kochanska, 2002 16 By 45 months, effortful control stable longitudinally & across tasks Less intense proneness to anger and joy, & more inhibited to unfamiliar in 2nd year developed higher effortful control. Higher effortful control at 22–45 months stronger conscience at 56 months & fewer externalizing problems at 73 months. – Effortful control mediated the oft-reported relations between maternal power assertion and impaired conscience development in children, even when child management difficulty was controlled. Kochanska, G., & Knaack, A. (2003). Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: antecedents, 17 correlates, and consequences. J Pers, 71(6), 1087-1112. Prosocial integrative model Rises with age Stronger in girls Influenced by sociability, social competence, regulation of emotion “Some consistency” in prosocial behavior Strong situational influences – 6/30/2016 Diverse measures Messinger (p. 743) Cross-cultural Cultures in which children are more prosocial tend to involve extended families, strong female role, less division of labor – 6/30/2016 Reciprocal prosocial obligations valued as/more highly than individual obligation Messinger 24 Family Good parenting good empathy – – Kochanska Empathy springs from brain-based caregiving systems associated with mothering/parenting De – 6/30/2016 Waal; Panksepp (706) Siblings caring for younger sibs Messinger 25 Discipline Inductive parenting– ‘How do you think David feels?’ linked to pro-social behavior/sympathy Power assertive techniques do not work as a modal technique, but can be important in a more reciprocal context Authoritative parenting – warmth and control – – – Regulation of negative emotion Plus role modeling for optimal prosociality And providing early pro-social opportunities 6/30/2016 Foot-in-the-door technique Messinger 26 Peer Acceptance and Social Cognition Social information processing Differences based on sociometric classifications? RUBIN ET AL., 2011 Prosocial behavior Voluntary behavior intended to benefit another – Empathy – – Understanding-based feeling of what other is feeling Sympathy – Sorrow/concern for other – Different from personal distress – – Self-focused aversive negative emotional reaction to other 6/30/2016 Linked to helping, HR down Linked to getting out of there, HR up So regulating negative emotion is important Messinger 28 Precursors to morality in development as a complex interplay between neural, socioenvironmental, and behavioral facets Jason M. Cowell and Jean Decety The Child Neurosuite, Department of Psychology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL PNAS | October 13, 2015 | vol. 112 | no. 41 | 12657–12662 Billingsley 29 Background Preferential-looking tasks and other studies of attention suggest that children < 2 yr prefer prosocial actors Selective attention: preferential attention extends to as young as 3-months-old Selective approach: by 6 months Interpretation of early social preferences unclear Billingsley 30 Goal & Methods Goal: Investigate the neural bases of third-party social evaluations in infants and toddlers, and their link to parental values 73 children between 12 & 24 months Parents complete questionnaire: Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire VSF Sensitivity to Justice Scale Interpersonal Reactivity Index Infant EEG & Eye-tracking Billingsley 31 Methods Social Evaluation Task: observe prosocial (helper) vs. antisocial agents (hinder) Preferential Reaching Paradigm 4-minute resting state Chicago Moral Sensitivity Task: two characters interact in a variety of prosocial or antisocial ways Sharing Game Billingsley 32 Results No evidence of preferential reaching for prosocial character Equal numbers of children shared vs. did not share at least one toy Sharing associated with effortful control, but not positive or negative affect Sharing associated with parent’s perspective-taking and (negatively) with parent’s personal distress Billingsley 33 Results During SET Greater cortical activation in helping vs. hindering condition Greater left frontal asymmetry when viewing hindering vs. helping – Consistent with activation of avoidance response Greater fixation on agent of helping vs. receiver of help – But no greater fixation on prosocial vs. antisocial action Billingsley 34 Results From CMST Greater amplitude for prosocial vs. antisocial scenes (parietal region; 300-500ms) – More computation required to process the prosocial, or the prosocial is more novel No differences found 200-300ms, or 600-1000ms Prosocial reaching preferences predicted by individual differences in activation when perceiving helpful vs. harmful behavior (200-500ms & 600-1000ms) Those individual differences in turn were predicted by parental sensitivity to injustice (300-500ms only) Billingsley 35 Results From CMST Greater amplitude for prosocial vs. antisocial scenes (parietal region; 300-500ms) – More computation required to process the prosocial, or the prosocial is more novel No differences found 200-300ms, or 600-1000ms Prosocial reaching preferences predicted by individual differences in activation when perceiving helpful vs. harmful behavior (200-500ms & 600-1000ms) Those individual differences in turn were predicted by parental sensitivity to injustice (300-500ms only) Billingsley 36 Social preferences associated with neural activation during CMST Billingsley 37 Conclusion Infants and toddlers distinguish between prosocial & antisocial acts: EEG and eyetracking evidence The distinctions appear rooted in basic processes of approach/withdrawal and attention Billingsley 38 Social Exclusion: Hypothetical Stories vs. Observed in Lab • Hypothetical stories depicting social exclusion “What would you do?” • Responses coded as: • Assertive • Indirect • Withdrawal • Redirect Real life exclusion – Ball Toss Game What does child do? • Responses coded as: • • • • • Assertive Indirect Withdrawal Redirect Video examples Family environment Patterns seen across maltreatment types – – – – – Family environment of coercion and abuse of power Lower levels of prosocial behavior and verbal communication Undervaluing of children Deviant affective displays Maternal intrusiveness and non-responsiveness Acosta Social development and abuse Abuse negatively impacts peer relationships and self-concept – – particularly if its frequent and of long duration though a strong friendship may attenuate this relationship Investigated with 107 children experiencing various types of abuse and 107 comparison children between 2nd and 7th grade • 6/30/2016 Bolger et al 1998 Messinger 42 Social and emotional adjustments Maltreated children often suffer from low self-esteem, self-blame, and negative affect toward the self Greater risk for peer rejection – The longer maltreatment occurs, the greater the likelihood of rejection, perhaps because of tendency to engage in coercive, aggressive interactions with peers as result of abuse Timing and type of maltreatment influence consequences Chronic maltreatment - less popular Earlier emotional maltreatment – Chronic physical abuse – Low & decreasing reciprocated playmates Sexual abuse and frequent physical abuse – 6/30/2016 decreasing friendship quality Chronic and frequent maltreatment – less likely to have a reciprocated best friend lower self-esteem Messinger 46 Good friendships protect High friendship quality and reciprocated friendships associated with resistance to negative impact of chronic maltreatment and physical abuse on self-esteem • 6/30/2016 Figs 5 - 7 Messinger 47 Chronically maltreated kids likely to be rejected by peers Maltreatment chronicity higher levels of children's aggressive behavior – reported by peers, teachers, and children Aggressive behavior accounted for association of maltreatment and rejection. – Socially withdrawn behavior associated with peer rejection but did not account for the association between chronic maltreatment and peer rejection. Results hold for both girls and boys – Bolger & Patterson, 2001 Maltreatment chronicity peer rejection Maltreatment Aggression Maltreatment, aggression, & rejection Specificity of abuse effects Sexual abuse predicted low self-esteem – Emotional maltreatment was related to difficulties in peer relationships – but not peer relationship problems. but not to low self-esteem. For some groups of maltreated children, having a good friend was associated with improvement over time in self-esteem. • Bolger et al., 1998 Does abuse predict malfunction? Many children and adolescents who suffer maltreatment become well-functioning adults Maltreatment can result in significant negative consequences that continue into adulthood Although many survivors function well in adulthood, others suffer serious psychological distress and disturbance Why? Maltreating parents may fail to produce opportunities for positive social interaction for their children Children who experienced a lack of parental supervision were less likely to be accepted by peers – Tendency to engage in unskilled or aggressive behavior Possible buffers Maltreating parents may fail to produce opportunities for positive social interaction for their children – Opportunities found elsewhere (i.e., other family members, friends, teachers, etc.) Maltreated children with best friends are more likely to experience increased selfesteem and self-concept than other maltreated children Cognitive adaptations Maltreated children create defensive structure in reaction to trauma – Cognitive distortions, dissociation, vigilance Hypervigilance: constant scanning of environment and development of ability to detect subtle variations in it Dissociation: alter level of self-awareness in an effort to escape an upsetting event or feeling – Psychological escape Acosta Emotion regulation Involves ability to modify, redirect, and control emotions Maltreated children engage in efforts to avoid, control or suppress emotion Modulation difficulties: extreme depressive reactions and intense angry outbursts Internalizing behavior problems Anger recognition & physical abuse Physically abused children displayed a response bias for angry facial expressions. – abused 8-11-year-olds demonstrated increased attentional benefits on valid angry trials • • demonstrated delayed disengagement when angry faces served as invalid cues. Pollak & Tolley-Schell. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 112(3), Aug 2003, 323-338. Abused see more anger Messinger At expense of sadness Recognizing emotion in faces Controls viewed discrete emotions discretely Neglected children saw fewer distinctions Neglected children had more difficulty discriminating emotional expressions than control or physically abused children. Physically abused children showed the most variance across emotions. – Pollak, Cicchetti, Hornung, Reed, Developmental Psychology. 36(5), Sep 2000, 679-688. Neglected children don’t distinguish emotion expression pairs Mean similarity ratings by emotion pair for control (C; solid line), neglected (N; dotted line) and physically abused (PA; dashed line) children. A = angry, N = neutral, S = sad, F = fearful, D = disgusted, H = happy Heart rate change scores (bpm) Active anger: Large initial deceleration for both abused and non-abused children – Reflects attentional orienting response Unresolved anger: Eventual recovery from initial deceleration Resolution: Greater recovery for non-abused than abused children Pollak, Vardi, Bechner, & Curtin (2005). Physically Abused Impact on emotion recognition Influence of early adverse experience on children's selective attention to threatrelated signals is a mechanism in the development of psychopathology. As children's experience varies, so will their interpretation of emotion expressions. • Pollak & Tolley-Schell. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 112(3), Aug 2003, 323-338. Overlap with risky behaviors Increased likelihood to engage in a greater array of risky behaviors Certain types of maltreatment associated with a greater number of sexual partners and heavier alcohol consumption Adult survivors likely to engage in substance abuse, criminal and antisocial behavior, and eating disorders