Methodological Issues

advertisement

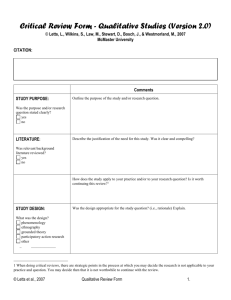

Methodological Issues 2007 CFRF Annual Workshop Jill Belsky Professor and CFRF steering committee member 1. Why care about “rigour”? 2. Some methodological “tools” 3. Some references 4. Your ideas, comments, questions 1. Why care about rigour (not rigor mortis)? (Neef 2003: 4) “Following a boom period throughout the 1990s, the theoretical, conceptual and methodological foundations of participatory approaches have attracted increasing criticism in the last years. Among the main issues noted were methodological limitations and lack of scientific rigour.” Examples? a. b. c. d. insufficient analysis too much researcher bias limited precision of approaches and systemic validation of results concealed interests of marginalized individuals who are not in organized groups Defining rigour in PAR: Branigan 2003:37 “…rigour is evident in research when the methods used are those that can represent the fullest, most detailed, rich and expressive picture of a particular situation...Rigour is in large part dependent on the researchers themselves Swepson 2000:8 “…a more appropriate criterion of rigour is the degree of the relevance of the methodology to the problem; the one which best allows the researcher to conduct systematic inquiry in order to present a warranted assertion—that is, the methodology is fit for a given function.” 2. Some Methodological Tools 1. Relevance -what is the research question and why are you asking it? -who or what is it intended to benefit from it and how? -how are you defining “relevance”? if to increase knowledge, whose knowledge? if to increase empowerment, whose empowerment? if to increase action, who wants it to happen? -what information is most relevant and which method(s) most likely to gather it? 2. Triangulation (cross-checking results) -compares the results from either two or more different methods of data collection or two or more data sources from same method -search for patterns of convergence to develop or corroborate an interpretation -a type of test of validity because it assumes that any weakness in one method will be compensated by strengths in another (i.e., different methods as well as researchers are more or less able to “see” a part or slice of the total situation). 3. Combining and mixing methods Not all research questions, or points along the research process, require the same level of local/community participation Standards such as interviews, focus groups, surveys, participant obs., ethnography… and also mapping, transect walks, seasonal calendars, time/resource use/other trend analyses, venn diagramming (social networks, groups), matrix scoring and ranking, drama and participatory video making…. Yes, its okay and maybe even necessary to mix methods from quantitative and qualitative research! 4. Participant feedback -especially relevant to qualitative or interpretative research methods -investigator’s account is compared with those of the research subjects (eg “is that what you said?) and their reactions are incorporated into the study findings -a related technique is to use “low inference descriptors” or use of description phrased very close to participants’ accounts and researcher’s field notes, such as direct quotations 5. Clear exposition of methods of data collection and analysis; context - provide a clear account of how data were collected and analyzed, assumptions made, context (“audit trail”) -written account should include sufficient information and data to allow the reader to judge whether the interpretation offered is adequately supported by the data and is credible - a related method would be to discuss all of the above with other people, including peers who are familiar with or disinterested in the research – 6. Critical Reflection -”reflection” means “turning back” on experience to be aware of the ways in which the researcher and the research process shape the data, interpretations, and actions (especially prior assumptions and experiences) -”critical” includes questioning taken-for-granted beliefs that relate to our experiences and how we make meaning of it (including our research); question our personal and intellectual biases and make these transparant; pose new questions for ourselves as to how we can reframe our inquiry for new possibilities for thought and action 7. Attention to negative cases - in addition to providing serious exploration of alternative explanations for the data collected and interpreted, involves a search for and discussion of factors in the data that contradict the explanation provided 8. Fair dealing - attempt to incorporate a wide range of different perspectives so that the view point of one individual or group is not overstated (very relevant to com forestry!) - may suggest conventional (random) sampling techniques are warranted Take away points -the questions to be answered and actions to be fostered are determined by the researcher and community groups -the questions determine the methods to be used no method is inherently “participatory” or not, though some are more effective than others to foster dialogue, trust, reveal power and political conflict context -PAR can and should be rigorous based on definitions and criteria discussed here and throughout the workshop -participatory researchers build on standard research methods – alone or in combination plus others, emphasizing self-critique and reflection, innovation, resourcefulness, collaboration, respect for multiple knowledge systems, production and methods! 3. Some References Branigan, E. 2003. ‘But how can you prove it? Issues of rigour in action research. Journal of the HEIA 10(3):37-38. Denzin, N. and Lincoln. Y. (Eds.). 1994. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Finn, J.L and M. Jacobson. 2003. Just Practice: A Social Justice Approach to Social Work.Eddie Bowers Pub., Iowa. Mays, N. and C. Pope. 2000. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320(50-2). [Download from bmj.com] Neef, A. 2003. Participatory approaches under scrutiny: will they have a future? Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture 42(4):489-497. Sutherland, A. 1998. Participatory research in natural resources. Natural Resources Institute, The University of Greenwich. Swepson, R. 2000. Reconciling action research and science. In Branigan, E. 2003. ‘But how can you prove it? Issues of rigour in action research. Journal of the HEIA 10(3):37-38. 4. Your ideas, observations and questions…