Class Lecture Notes 11.doc

advertisement

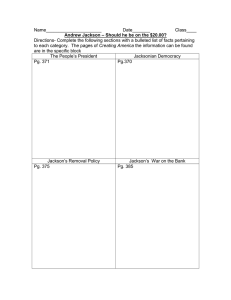

The American Promise – Lecture Notes Chapter 11- The Expanding Republic, 1815 - 1840 I. The Market Revolution A. Improvements in Transportation 1. Changes in Commerce, Travel, and Politics—Between 1815 and 1840, networks of roads, canals, steamships, and railroads dramatically raised the speed and lowered the cost of travel; moved goods into wider markets; moved people to new locations and new jobs; facilitated the flow of political information, newspapers, periodicals, and books via the U.S. mail; enhanced public transport was expensive; presidents were reluctant to fund it because it produced uneven economic benefits; only the National Road between Baltimore and Wheeling was government funded; state governments provided subsidies for private transportation investors. 2. Steamboats—Robert Fulton’s steamboat the Clermont traveled the Hudson River from New York City to Albany; touched off a steamboat craze and transformed water travel; steamboats could be dangerous; competition led to overstocked furnaces, boiler explosions, and terrible mass fatalities; wood-fired engines led to mass deforestation; smoke in the air created the nation’s first air pollution. 3. Canals—Shallow highways of water allowed passage for boats pulled by mules; travel was slow (less than five miles per hour), but the low-friction water enabled one mule to pull a fifty-ton barge; Erie Canal, finished in 1825, linked New York City with the Great Lakes region. 4. Railroads—Private railroad companies began to give canals competition in the 1830s; three thousand miles of tracks were constructed in the 1830s; generally short and inefficient, but quickly became popular; railroads and other transportation advances encouraged change by linking the country culturally and economically. B. Factories, Workingwomen, and Wage Labor 1. The Lowell Mills—First American factories featured mechanical spinning machines; unlike British factories, they targeted young women as employees because they were cheaper to hire and had limited employment options; town of 1 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes Lowell was founded in 1821 by a group of entrepreneurs; Lowell mills centralized all aspects of cloth production and employed more than 5,000 young women; workers lived in company-owned boardinghouses under close supervision; women were required to join the church; women worked there to earn spending money and gain unprecedented, though still limited, personal freedom of living away from parents and domestic tasks; contributed to the company newspaper, the Lowell Offering. 2. Worker Protest—Growth and competition in the cotton market led mill owners to speed up work and decrease wages; workers protested, emboldened by communal living arrangements and relative independence as temporary employees; on the other hand, they could easily be fired and replaced, which undermined their bargaining power. C. Bankers and Lawyers 1. The Explosion of Banks—Number of state-chartered banks doubled between 1814 and 1816; banks stimulated the economy by making loans to merchants and manufacturers and enlarging the money supply; bankers had power over the economy by deciding who would get loans and what the rates would be; most powerful was the second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia. 2. The Revolution in Commercial Law—In 1811, states began rewriting laws of incorporation, and the number of corporations expanded rapidly from twenty in 1800 to eighteen hundred by 1817; incorporation protected individual investors from being held liable for corporate debts; created the legal foundation for an economy that favored ambitious individuals interested in maximizing their own wealth. 3. Opposition to Change—Andrew Jackson spoke for many when he criticized new corporate privileges; he believed that ending government-granted privileges was the way to maximize individual liberty and economic opportunity. D. Booms and Busts 1. The Panic of 1819—Lawyer politicians could not control the volatile economy; speculation held the possibility of financial collapse; when the bubble burst in 1819, the overnight rich became the overnight poor; some blamed the panic of 1819 on the second Bank of the United States for failing to control state banks; the national bank started calling in loans and insisted states do the same; contraction of the money supply was made worse by a financial crisis in Europe; prices of American exports plummeted; debtors couldn’t pay back their debts, and banks failed. 2 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. Recovery—Took several years and was driven by increases in productivity, consumer demand for goods, international trade, and a restless and calculating people moving goods, human labor, and capital in expanding circles of commerce. II. The Spread of Democracy A. Popular Politics and Partisan Identity 1. Popular Participation—The election of 1828 was the first presidential contest in which popular votes determined the outcome; in twenty-two of twenty-four states, voters—not state legislatures—chose the electors in the electoral college. 2. New Campaign Styles—State-level candidates gave speeches at rallies, picnics, and banquets; partisan newspapers increasingly defined issues and publicized political personalities as never before; improved printing technologies and increasing literacy made this possible. 3. New Parties—Politicians at first identified themselves as Jackson or Adams men; honoring the fiction of Republican Party unity; party lines solidified by the mid-1830s with two new parties, the Whigs and the Democrats. them to comprehend the kind of B. The Election of 1828 and the Character Issue 1. The Importance of Character—Character issues reigned supreme in 1828; voters used public official each man would make. 2. Jackson and Adams—Radically different styles of manhood; Adams was vilified by his opponents as an elitist, a bookish academic, and even a monarchist; Adams’s supporters played up Jackson’s violent temper. 3. The Triumph of Political Parties—Jackson won a sweeping victory with 56 percent of the popular vote; after 1828, national politicians no longer deplored the existence of political parties; believed parties mobilized and delivered voters, sharpened candidates’ differences, and created party loyalty; the Whigs were seen as the top-down party, whereas the Democrats embraced individualism. 3 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes C. Jackson’s Democratic Agenda 1. The Common Man—Jackson offered unprecedented hospitality to the public; installed spittoons in the White House; Jackson was committed to his image as the president of the “common man.” 2. The Spoils System—Past presidents tried to lessen party conflict by including men of different factions in their cabinets; Jackson appointed only loyalists, even replacing competent civil servants with party loyalists; became known as the spoils system. 3. Jacksonian Government—Jackson believed in a limited federal government; anticipated the rapid settlement of the nation’s interior, where land sales would spread economic democracy to settlers; led to anti-Indian policies; exercised presidential veto over Congress. III. Jackson Defines the Democratic Party A. Indian Policy and the Trail of Tears 1. The Indian Removal Act—Jackson argued that the government had to move Indians to the West in order to save their civilization from whites; Congress backed Jackson’s goal and passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830; appropriated $500,000 to relocate eastern tribes west of the Mississippi. 2. Petitions against Removal—Northern newspaper editors opposed removal, likening it to slavery; in an unprecedented move, thousands of northern white women signed petitions opposing the removal policy; argued especially that the Cherokee Indians of Georgia were a sovereign people on the road to Christianity. 3. Indian Resistance—Volunteer militias attacked and chased the Sauk and Fox Indians into Wisconsin; deadly battle killed more than four hundred Indians; Creeks, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Cherokee tribes in the South refused to relocate; second Seminole War in Florida broke out as Indians there took up arms against relocation. 4 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 4. Georgia Cherokees—Made a legal challenge to being treated as subjects; in 1831, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Cherokee people lacked standing to sue, not being citizens of either the United States or of any foreign state; the next year, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Court upheld the territorial sovereignty of the Cherokee people; Jackson ignored the Court’s decision and continued to press for removal. 5. The Trail of Tears—In 1835, an unauthorized faction of Cherokees signed a treaty selling all tribal lands to the state; Georgia resold the land to whites; the Cherokee faced a deadline of May 1838 for voluntary evacuation; when they refused, they were forced on a 1,200-mile journey west under armed guard; the hardship of this journey, which came to be called the Trail of Tears, killed 25 percent of the traveling Cherokees. III. Jackson Defines the Democratic Party B. The Tariff of Abominations and Nullification 1. High Tariffs and the “Tariff of Abominations”—Federal tariffs as high as 33 percent on imports such as textiles and iron goods had been passed in 1816 and again in 1824 to shelter American manufacturers from foreign competition; southern congressmen believed it hurt cotton exports; Congress passed a revised tariff in 1828, which came to be known as the Tariff of Abominations; bundle of conflicting duties, some as high as 50 percent; contained provisions that angered every economic and sectional interest. 2. The Doctrine of Nullification—South Carolina in particular suffered; a group of politicians headed by John C. Calhoun advanced a doctrine called nullification; argued that when Congress overstepped its powers, states had the right to nullify Congress’s acts; referenced the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798. 3. The Nullification Crisis—On assuming the presidency in 1829, Jackson ignored the statement of nullification and shut out his vice president, Calhoun, from influence and power; Calhoun resigned in 1832 and won a seat in the Senate; South Carolina leaders declared federal tariffs null and void as of February 1, 1833; Jackson sent armed ships to Charleston harbor and threatened to invade the state; pushed the Force Bill through Congress, which defined South Carolina’s stance as treason and authorized military action to collect federal tariffs; Congress passed a revised tariff, and South Carolina responded by withdrawing its nullification of the old tariff and nullified the Force bill; federal power triumphed. D. The Bank War and Economic Boom 5 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 1. The Bank War—Jackson believed the bank concentrated undue economic power in the hands of a few; Whig Senators Daniel Webster and Henry Clay decided to force the issue; convinced the bank to apply for early charter renewal in 1832; expected Congress’s renewal would force Jackson to issue an unpopular veto and then lose the next election. 2. The Bank Veto—Congress did renew the charter, but Jackson’s veto made him all the more popular; invoked the language of class; discussed how the privileges of the moneyed elite oppressed the democratic masses to enrich themselves; Clay and his supporters found the language absurd, and they distributed thousands of copies of the veto; helped Jackson win the election. 3. A Booming Economy—Jackson took steps to destroy the bank sooner, and the economy declined briefly; but once unregulated, it went into high gear in 1834; led to inflation, the charter of hundreds of new banks, and the increasing density of credit and debt relationships; national debt disappeared, and for the first and only time in American history, between 1835 and 1837, the government had a monetary surplus. IV. Cultural Shifts, Religion, and Reform A. The Family and Separate Spheres 1. Separate Spheres—Held that husbands found their status and authority in the new world of work, while wives tended to the hearth and home; promoted by sermons, advice books, periodicals, and novels; gained acceptance in the commercialized Northeast, but had limited applicability outside of middle- and upper-class white women. 2. The Female Economy—As more men worked and earned cash outside the home, women’s housework was rendered invisible by an economy that evaluated work according to how much cash it generated; in reality, wives contributed directly to the family income in many ways, such as taking in boarders or doing needlework at home; poor wives, including most black wives, had to work outside the home. 3. Idealized Notions of Masculinity and Femininity—Notions about the feminine home and the masculine workplace gained ascension in the 1830s and beyond because of the cultural ascendancy of the commercialized Northeast; men seeking manhood through work and pay could embrace competition and acquisitiveness; women established femininity through dutiful service to home 6 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes and family; new ideals had little applicability beyond the men and women of the middle classes. B. The Education and Training of Youths 1. Public Schools—The market economy required expanded opportunities for training youth of both sexes; state-supported public schools were the norm in the North and South by the 1830s. 2, Female Teachers—Literacy for white females climbed dramatically; the fact that taxpayers paid for public schools created an incentive to seek an inexpensive teaching force; by the 1830s, school districts replace male teachers with young females. 3. Higher Education and Career Opportunities—Colleges expanded in the 1830s, with an additional two dozen colleges for men and several more female seminaries opening; but only a very small percentage of young people attended institutions of higher learning; vast majority of male youth left public school at age fourteen to apprentice in trades or seek entry-level clerkships; young women headed for mill towns or cities; changes in patterns of youth employment and training meant that large numbers of young people in the 1830s and beyond escaped the watchful eye of their families. C. The Second Great Awakening 1. Protestantism Reinvigorated—Protestantism gained momentum in the 1820s and 1830s; earliest manifestation of fervent piety marking the start of the Second Great Awakening appeared in 1801 in Kentucky in the form of a revival meeting that lasted several weeks; by the 1810s and 1820s, camp meetings had spread to the Atlantic seaboard; attracted women and men hungry for a more immediate access to spiritual peace, one not requiring years of soul searching; women more so than men were attracted; church membership doubled in the United States from 1800 to 1820. 2. Charles Grandison Finney—Leading exemplar of Second Great Awakening; lawyer-turned-minister; message primarily directed at the business classes; public outreach could lead to salvation; sustained a six-month revival in Rochester through the winter of 1830–1831; adopted the tactics of Jacksonian politicians—publicity, argumentation, rallies, and speeches—to sell his cause. D. The Temperance Movement and the Campaign for Moral Reform 7 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 1. Alcohol Consumption—Evangelical disposition animated a vigorous campaign to eliminate alcohol abuse; alcohol consumption had risen steadily up to 1830; in 1826, Lyman Beecher founded the American Temperance Society; argued that drinking led to poverty, idleness, crime, and family violence; regrouped into a new society in 1836, the American Temperance Union; demanded total abstinence from its adherents; middle class drinking began a steep decline. 2. Moral Reform—Moral reformers aimed first at public morals in general but quickly narrowed to a campaign to eradicate sexual sin, especially prostitution; in 1833, a group of Finneyite women started the New York Female Moral Reform Society; condemned men who visited brothels or seduced innocent women; did not regard themselves as radicals; pursuing the logic of gender system that defined home protection and morality as women’s special sphere and a religious conviction that called for the eradication of sexual sin. Organizing against Slavery 1. Abolitionism—Most radical movement; around 1830, northern challenges to slavery surfaced with increasing frequency and resolve; writers like David Walker and public speakers like Maria Stewart offered critiques of slavery and racism; Stewart was especially controversial, as many Americans resented any woman, particularly a black woman, speaking in public. 2. The Liberator—Newspaper founded in Boston in 1831 by William Lloyd Garrison; took antislavery to new heights by advocating for immediate abolition; Garrison’s supporters started the New England Anti-Slavery Society. 3. White Violence—Many white northerners, even those who opposed slavery, were not prepared to embrace the abolitionist cause; from 1834 to 1838, there were more than a hundred eruptions of serious mob violence against abolitionists and free blacks. 4. Women’s Activism—Women played a prominent role in activism, just as they did in reform and evangelical religions; they raised money and circulated petitions to support the cause; the white Grimké sisters were banned by the state leaders of the Congregational Church from speaking in their churches; the Grimkés and other radical abolitionists argued for women’s rights as well; 8 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes opposed by moderate abolitionists who were unwilling to mix the new and controversial issue of women’s rights with their first cause, the rights of blacks. V. Van Buren’s One-Term Presidency A. The Politics of Slavery 1. Determining Jackson’s Successor—Jackson favored Martin Van Buren for the election of 1836; John C. Calhoun was Van Buren’s archrival; he tried to discredit Van Buren among southern Democrats and whipped up controversy over Van Buren’s 1821 support of suffrage for propertied free blacks in New York. 2. Slavery as a Political Issue—The slavery issue was increasingly volatile as northern abolitionists gained strength; southerners becoming alarmed; abolitionists sent petitions demanding that Congress “purify” the District of Columbia by outlawing slavery there. 3. The Gag Rule—Congress passed a “gag rule” in 1836 that prohibited the entering of abolitionists’ petitions into the public record; abolitionists were outraged. 4. Van Buren’s Strategy—Van Buren decided to seize on the gag rule to express pro-Southern sympathies; he dismissed abolition in Washington, D.C., as inexpedient and repeated that as president, he would not allow any interference in southern “domestic institutions. B. Elections and Panics 1. The Election of 1836—The Whigs had no top contender with national support, so three regional candidates opposed Van Buren; Van Burenites called the three-Whig strategy a deliberate plot to send the election to the House of Representatives; Van Buren won the vote, but his majorities where he won were far below those Jackson had commanded; he had won in the North by committing northern Democrats to the proslavery agenda; running three candidates also drew Whigs into office at the state level. 2. The Panic of 1837—Nation plunged into economic crisis a month after Van Buren took office; many causes: a trade imbalance between Britain and the 9 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes United States, failures in crop markets, and a downturn in cotton prices on the international market among them. 3. Explaining the Panic—Many observers looked to politics, religion, and character flaws to explain the crisis; Whig leaders blamed Jackson’s antibank and hard-money policies; others framed it as retribution for an immoral frenzy of speculation; the downturn subsided by 1840, but it hurt Van Buren politically. 4. The Election of 1840—Whigs nominated war hero William Henry Harrison to oppose Van Buren; campaign drew voter involvement as had no other presidential campaign; Harrison campaigned as a common man and won the election using campaign techniques developed by Jackson and the Democrats, including rallies and barbecues. 10 of 10