Class Lecture Notes 9.doc

advertisement

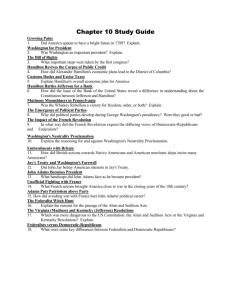

The American Promise – Lecture Notes Chapter 9 - The New Nation Takes Form, 1789-1800 I. The Search for Stability (Slide 2) Page 241 A. Washington Inaugurates the Government Page 242 1. Washington’s Election—Washington was elected unanimously in February 1789; tallying of the votes in the electoral college was a mere formality; Adams became vice president. 2. Establishing the Presidency—Washington calculated his moves once in office, as he understood that his every step set a precedent and that a misstep could harm the fragile new government; his genius in establishing the presidency lay in his capacity for implanting his own reputation for integrity into the office itself; Washington was not a brilliant thinker or congenial man, but he was “virtuous,” meaning he took pains to elevate the public good over private interest and projected honesty and honor over ambition; he remained aloof and dignified, and he encouraged ceremony to create respect for the office. 3. The First Cabinet—Washington chose talented and experienced men to preside over new offices; General Henry Knox led the Department of War; Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton to lead the Department of the Treasury; Thomas Jefferson was named head of the Department of State; Edmund Randolph was the new attorney general; John Jay became the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. B. The Bill of Rights Page 243 1. A Condition of Ratifying the Constitution—Seven states had ratified the Constitution on the condition that guarantees of individual liberties and limitations to federal power be swiftly incorporated; became an important piece of business for the First Congress. 2. Madison’s Language—Madison pulled much of his wording directly from various state constitutions with bills of rights; the Bill of Rights enumerated guarantees of freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to petition and assemble; the right to be free from unwarranted searches and seizures; and the right to bear arms in support of a “well-regulated militia.” 1 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. Ratifying the Bill of Rights—State ratification took two years, but there was no serious doubt about the outcome; the states ratified ten of the original twelve amendments. 4. A Key Omission—No one complained about the omission of the right to vote; only much later was voting seen as a fundamental liberty requiring protection from constitutional amendment. C. The Republican Wife and Mother (Slide 3) Page 244 1. Redefining Virtue—Periodical articles in the 1790s by both male and female writers reevaluated courtship, marriage, and motherhood in light of republican ideals; affection, not duty, bound wives to their husbands; virtue of sexual chastity enlarged in importance and became prized as a feminine quality; essayists advised young women to use sexual virtue to increase public virtue in men. 2. Republican Motherhood—Advocates for female education argued that education would produce better mothers who in turn would produce better citizens; historians call this concept republican motherhood; Benjamin Rush advocated in favor of female education; Judith Sargent Murray favored education that would remake women into self-confident, rational beings. 3. Politicizing Domesticity—Politics was still a masculine preserve, but women’s domestic obligations were now infused with political meaning; still failed to alter traditional gender relations. II. Hamilton’s Economic Policies (Slide 4) Page 245 A. Agriculture, Transportation, and Banking 1. Agriculture—Increases in international grain prices led to increased agricultural production for export trade; generated new jobs; Eli Whitney’s cotton gin dramatically increased cotton production as well. 2. Road Building—The establishment of the U.S. Post Office in 1792 increased road mileage sixfold; private companies also built toll roads; the number of stagecoach companies increased; cut travel time in half in the northeast. 2 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. Commercial Banking—Commercial banking also grew dramatically in the early republic; the number of banks nationwide multiplied from three in 1790 to twentynine in 1800; the U.S. population also increased 35 percent. B. The Public Debt and Taxes Page 247 1. The Report on Public Credit—The upturn in the economy suggested the government might soon pay off its wartime debt; Hamilton had a different plan: his Report on Public Credit, published January 1790, argued debt should be funded—but not repaid immediately—at full value; there would still be a public debt, but it would be secure, giving its holders a financial stake in the new government; goal was to make the country creditworthy, not debt free. 2. Controversy—Funding the full debt was controversial because speculators had bought up debt certificates; Hamilton also caused controversy because he proposed to add to the federal debt another $25 million in assumed state debts; states who had already paid their debts believed this plan was unfair; the plan would consolidate federal power over the states. 3. Compromise—Congressman James Madison objected to putting profits in the pockets of speculators and opposed Hamilton’s plan; Thomas Jefferson arranged a compromise between Madison and Hamilton; Madison would restrain his opposition to the debt plan; in turn, Hamilton pledged to back efforts to locate the nation’s new capital city in the South, along the banks of the Potomac River. C. The First Bank of the United States and the Report on Manufactures (Slide 7) Page 248 1. A National Bank—Hamilton proposed a national Bank of the United States, modeled on European central banks, as a private corporation that worked primarily for the public good; the federal government would hold 20 percent of the bank’s stock, making the bank the government’s fiscal agent; the other 80 percent of capital would come from private investors; Madison feared that the bank would allow a few rich bankers to have undue influence over the economy; he tried and failed to block the plan. 2. Hamilton’s Report—Issued in December 1791; a proposal to encourage the production of American-made goods; the federal government would grant subsidies to manufacturers and impose moderate tariffs on those same products from overseas; never approved or even voted on by Congress; Madison and 3 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes Jefferson believed the “general welfare” clause of the Constitution did not include public subsidies to private businesses. D. The Whiskey Rebellion Page 250 1. The Whiskey Tax—Hamilton’s plans required taxation to pay the interest on the national debt; he convinced Congress to pass a 25 percent excise tax on whiskey; the tax would be paid by farmers when they brought their grain to the distillery, then passed on to individual whiskey consumers in the form of higher prices. 2. Criticism—Tax was unpopular with grain farmers in the west and whiskey drinkers everywhere; in 1791, farmers in Kentucky and in the western parts of Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas complained to Congress about the tax; simple evasion of the law was the most common response; crowds also threatened to tar and feather federal tax collectors; Hamilton tightened up the prosecution of tax evaders. 3. Resistance in Western Pennsylvania—in western Pennsylvania, tax collector John Neville refused to quit; he filed charges against seventy-five farmers and distillers for tax evasion; at the end of July, seven thousand Pennsylvania farmers planned a march—or perhaps an attack, some thought—on Pittsburgh; Washington in response nationalized the Pennsylvania militia and set out, with Hamilton at his side, at the head of thirteen thousand soldiers; the demonstration had evaporated before the army arrived. 4. The New Government Flexes Its Muscles—While some, including Thomas Jefferson, believed the government had gone too far, the Whiskey Rebellion presented an opportunity for the new federal government to flex its muscles and stand up to civil disorder. III. Conflict on America’s Borders and Beyond (Slide 9) Page 251 A. Creeks in the Southwest 1. Negotiating with Georgia Creeks—Washington and his Secretary of War Henry Knox wanted peace with Indians, partly out of a sense of fair play but also over worries about the expense of warfare; they sent a delegation to Georgia to negotiate with Creek chief Alexander McGillivray; offered McGillivray a guarantee of extensive tribal lands and protection from white soldiers if they ceded disputed land where settlers already lived; McGillivray sent them away. 4 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. The Treaty of New York—A year later, Knox tried again; invited McGillivray to New York to meet with the president himself; the resulting 1790 Treaty of New York incorporated Knox’s original plan; never fully implemented. 3. Continued Conflict—In the end, the demographic imperative of explosive white population growth, land-seeking settlers, and speculation meant that confrontation with Natives was nearly inevitable. B. Ohio Indians in the Northwest Page 253 1. U.S. Army Enters Western Ohio—A doubled American population greatly intensified pressure for western land; the U.S. Army entered the western half of Ohio, where white settlers did not dare to go; troops led by General Josiah Harmar fell to defeat at the hands of Miami and Shawnee Indians; defeat spurred efforts to clear Ohio for permanent American settlement. 2. Military Action—General Arthur St. Clair had pursued peaceful tactics in the 1780s; after Harmar’s defeat, he geared up for military action; Indians attacked his forts on November 4, 1791; 55 percent of the Americans were dead or wounded before noon; only three of the women escaped alive; Washington doubled the U.S. military presence in Ohio and appointed new commander General “Mad” Anthony Wayne; engaged in skirmishes with Shawnee, Delaware, and Miami Indians throughout 1794; defeated the Indians at the battle of Fallen Timbers. 3. Treaty of Greenville—Negotiated in 1795; Americans offered treaty goods worth $25,000 and promised additional shipments every year; hoped to create Indian dependence on American goods; in exchange, the Indians ceded most of Ohio to the Americans; allowance of goods from Americans did not help Indians, as much of it came in the form of liquor. C. France and Britain (Slide 11) Page 255 1. The French Revolution and Pro-French Sentiment—The French Revolution had raged since 1789; initial American reaction was positive; pro-French political clubs sprang up; many American women exhibited solidarity with revolutionary France by wearing pro-French headgear; many Americans opposed the excesses of the revolution, however. 5 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. War between France and Britain—French versus British loyalty became a foreign policy debate in 1793, when Britain and France went to war; some Americans wanted to repay France for its aid during the American Revolution, while others were shaken by the report of the French Revolution’s excesses. 3. Neutrality Proclamation—Washington issued the Neutrality Proclamation in May 1793, which contained friendly assurances to both sides; American ships continued to trade between the French West Indies and France; in late 1795 and early 1794, the British captured American ships in response; Washington sent John Jay to England to negotiate commercial relations in the British West Indies and to secure compensation for American ships the British had seized; also sought to get Britain to reimburse southern planters for the slaves lured away by the British during the war; western settlers wanted the British to vacate the frontier. 4. The Jay Treaty—The result of John Jay’s mission to England to negotiate commercial relations and secure compensation for the seized American ships; did not address the captured cargoes or lost slave property; allowed the British eighteen months to withdraw from the frontier and granted them continued rights in the fur trade; called for repayment with interest of the debts that some American planters still owed to British firms dating back to the Revolutionary War; in exchange, Jay secured limited trading rights in the West Indies and the agreement that some issues would be decided later by arbitration commissions; the treaty produced powerful opposition across the nation. D. The Haitian Revolution Page 258 1. Race and power in Haiti—The Haitian Revolution was a complex event involving many participants; some 30,000 whites dominated the island, running plantations with the enslaved labor of close to half a million blacks; about 28,000 mixed-race people owned one-third of the island’s plantation and nearly a quarter of the slave labor force; despite their economic status, they were barred from political power. 2. The Revolution—The Haitian Revolution was inspired by the French Revolution; first, white colonists challenged the white royalist government, then mixed-race planters rebelled in 1791, then slaves rose up in 1793; slaves and free blacks led by Toussaint L’Ouverture aligned with Spain and occupied the northern regions of the island. 6 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. American Reactions—White Americans followed the revolution with fascinated horror; many black American slaves followed the news with amazement; the revolution provoked the fear of race war in the minds of many white southern Americans. IV. Federalists and Republicans (Slide 15) Page 259 A. The Election of 1796 1. Party Politics—Washington struggled to appear to be above party politics; in his farewell address, he stressed the need to maintain a “unity of government,” reflecting a unified body politic; leading contenders for Washington’s position, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, agreed in theory, but contests split along pro-British versus pro-French lines. 2. Federalists and Republicans—The Federalists informally caucused and chose Thomas Pinckney to run with Adams; the Republicans chose Aaron Burr to run with Jefferson. 3. The Results—Under the Constitution, each member of the electoral college could cast two votes for any two candidates, but on only one ballot; the top votegetter became president, and the next highest became vice president; Adams won and became president; Jefferson finished second and became vice president. B. The XYZ Affair Page 261 1. Conflict with France—Adams’s presidency was in crisis from the start; France retaliated for the British-friendly Jay Treaty by abandoning its 1778 alliance with the United States; French privateers started detaining American ships carrying British goods; Federalists started murmuring openly about war with France. 2. A Bribery Attempt—Adams dispatched a three-man commission to France in the fall of 1797; commission met with three unnamed French agents, soon known to the American public as X, Y, and Z; the commissioners said that $250,000 and a $12 million loan to the French government would be the price of a peace treaty; commissioners brought news of the bribery attempt to the president. 7 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. The Quasi-War—Americans reacted to the XYZ affair with shock and anger; the United States entered into its first undeclared war, called the Quasi-War; only intensified tension between Federalists and Republicans; Republicans believed Federalists wanted to raise the army to threaten domestic dissenters; Republican newspapers heaped abuse on Adams; pro-French mobs roamed the streets of Philadelphia, the capital; and Adams stocked weapons in his presidential quarters; Federalists in Massachusetts burned issues of the state’s Republican newspaper. C. The Alien and Sedition Acts Page 262 1. The Sedition Act—Federalist leaders moved to muffle the opposition; in 1798, Congress passed the Sedition Act, which made conspiracy and revolt illegal and penalized speaking or writing anything that defamed the president or Congress. 2. The Alien Acts—Congress passed two Alien Acts; the first extended the waiting period for an alien to achieve citizenship from five to fourteen years and required aliens to register with the federal government; the second empowered the president in a time of war to deport or imprison without trial any foreigner suspected of being dangerous; targeted the French, both potential French immigrants and the French already living in America. 3. Republican Opposition—Republicans argued the acts were in conflict with the Bill of Rights, but they did not have the votes to revoke the acts; federal judiciary dominated by Federalists as well. 4. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions—Jefferson and Madison pressed their opposition at the state level; each man drafted a set of resolutions condemning the acts and had the legislatures of Virginia and Kentucky present them to the federal government in the fall of 1798; resolutions argued that state legislatures had the right to judge the constitutionality of federal laws or even nullify them; had little effect on the Alien and Sedition Acts, but the idea of a state’s right to nullify federal law did not disappear. 5. One-Term Presidency—Adams refused to declare war on France as extreme Federalists had wished; he appointed new negotiators, and in 1800, the negotiations led to a treaty proclaiming friendship between the two nations; Federalists were not pleased, and Adams lost the support of his own party; election of 1800 openly organized along party lines. 8 of 8