Reading 2: Culture’n’Cognition Poster

advertisement

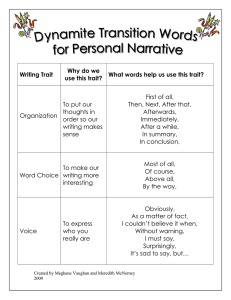

Cultural Differences in Inferences Made During Comprehension R. Brooke Lea Macalester College Karin M. Cox University of Pittsburgh Introduction Aaron D. Mitchel Pennsylvania State University David Matz Augsburg College Figure 1: Lexical Decision Response Times to Trait Probes Results 2000 • Nisbett and colleagues (e.g., Nisbett et al., 2001) propose that cultural differences in cognitive styles exist between East Asian and Western populations. • EastAsians tend to think more holistically, assign causality to the entire field, and make relatively little use of formal logic and categories. • Westerners tend to be more analytical, assume that causality emerges from objects, use rules including formal logic to understand behavior, and ignore contextual factors. • Supporting data has come primarily from perceptual rather than textual tasks. Trait Inferences (Figure 1) • We know that Western (American) subjects tend to make logical and trait inferences while reading (e.g., Lea, 1995; Winter & Uleman 1984), but we know little about the inferences made by East Asian populations. • A prediction, based on Nisbett et al. (2001), is that Western subjects should be most capable at logical and trait inferences whereas East Asians should excel at situational inferences. 1788 1768 1600 East Asian Population • No evidence of trait inferences during reading (F < 1) 1848 1400 1200 Western Population • Significant difference among the three means, F(2, 52) = 3.51, p < .05 • Follow-up tests indicated that the Trait/Trait probes were identified significantly faster than the probes in Baseline texts (p < .05), and marginally faster than the Situation/Trait probes (p < .057). • We tested this “Systems of Thought” hypothesis within the context of text comprehension. • We looked at three types of inferences: 1) propositional-logic (deductive) inferences 2) trait inferences that could explain a protagonist’s behavior 3) situational inferences relevant to a protagonist’s behavior 1800 1000 800 875 804 809 600 400 Situational Inferences (Figure 2) 200 0 East Asian Population • Significant difference among the three means, F(2, 52) = 4.13, p < .01 • Follow-up tests revealed that the probes following both the Sit/Sit passages and the Trait/Sit passages were identified significantly faster than those following the Baseline texts (p < .01, and p < .05, respectively). • The Sit/Sit and Trait/Sit conditions were not different from each other. Western Trait Passage East Asian Sit. Passage Baseline Figure 2: Lexical Decision Response Times to Situation Probes Western Population • Significant difference among the three means , F(2, 52) = 6.73, p < .01 • Follow-up tests indicated that the Situation/Situation probes were identified significantly faster than both the probes in Baseline texts (p < .05), and those that followed the Situation/Trait probes (p < .01). • The Trait/Sit and Baseline conditions were not different from each other. 1800 1766 1600 1622 1587 1400 1200 Method Logical Inferences (Figure 3) Participants • Western participants were born in a Western country and spoke a Western language (almost always English) as their native tongue. • East Asian participants originated from East Asian countries (e.g., Japan, Korea, China) and were native speakers of the mother tongue. • Thirty-six Macalester College students made up the Western pool, and 30 residents of the Twin Cities area made up the Eastern pool. 1000 East Asian Population • Significant difference between the inference and no-inference means, F(1, 26) = 6.47, p < .05 800 Western Population • Significant difference between the two means , F(1, 32) = 4.67, p < .05 400 Trait Inference Texts • In an example passage taken from Uleman et al. (1996), a businessman is dancing with his girlfriend and steps on her feet during the foxtrot (Table 1). • In the Trait-inducing version, the businessman has just spilled a drink on his girlfriend’s dress, and the foot-stomping appears due to his clumsiness. Indeed, Uleman and his colleagues have found evidence that the target trait CLUMSY is spontaneously activated (“spontaneous trait inference”). • We tested for trait inferences by asking participants to make lexical decisions on target traits, like CLUMSY. • We used two control conditions: 1) lexical decisions on the target trait after a completely unrelated text (Baseline Condition) 2) lexical decisions on the target trait after a similar text that promoted a situational attribution for the target behavior (i.e., the lack of room on the dance floor caused the foot fault). Situational Texts • Lupfer et al. (1990) modified Uleman’s trait passages so that situational factors appear to cause the focal behavior (Table 1). • In the situational version of the example text, the crowded dance floor explains why the businessman stepped on his date’s feet. • To test for situational inferences we asked participants to make lexical decisions on words related to situational elements related to the focal behavior. • We used two control conditions: 1) lexical decisions on the situational probe after an unrelated text (Baseline Condition) 2) lexical decisions on the situational probe after the trait-inference version of the text Logical Inference Texts • We used short passages that have reliably produced inference effects (e.g., Lea, 1995; Lea, Mulligan, & Walton, 2004). • In an example passage, Tony is deciding whether to have bread or cornflakes for breakfast (Table 2). He decides not to have corn flakes, and the reader can infer that he will have bread. This is not a pragmatic inference (one cannot call up from world knowledge what Tony had for breakfast); rather, it is a logical deduction based on the information presented in the premises, and the reader’s understanding of the logical particles or and not. • We tested for the “Or-Elimination” inference by asking participants to make lexical decisions on the inferred proposition (e.g., BREAD). • We also used a control condition in which Tony mentions but does not negate the “corn flakes” proposition. Summary • The five types of passages and three types of probes were used to produce 8 different experimental conditions (Table 3). Table 1 200 0 Trait Implying The businessman and his girlfriend plan a night on the town. They go to several nightclubs. He spills a drink on her dress. The businessman steps on his girlfriend’s feet during the foxtrot. Situation Implying The businessman and his girlfriend are celebrating his birthday. They are trying to dance on a very crowded dance floor. Everyone is bumping into others. The businessman steps on his girlfriend’s feet during the foxtrot. Control Text The gas station attendant was hungry. She left the counter to find food in spite of the rules against doing so. The attendant went to the fast food restaurant across the street. When she returned, her boss was waiting for her. Trait Probe: CLUMSY Situational Probe: NO ROOM Sit. Passage East Asian Trait Passage Baseline Figure 3: Lexical Decision Response Time to Logical Probes 1400 Western Population • Made trait inferences while reading trait-inference passages, as predicted • Also made trait inferences during the situational passages (though the effect was only marginally significant) • Unexpectedly, Westerns also made situational inferences while reading the situational passages. • The data suggest that Western readers activated both situational- and trait-related concepts while reading situational texts. • Westerns also made logical inferences, as has been demonstrated previously. 1200 1248 1329 1000 800 730 600 766 400 200 0 Western Logical Inference East Asian No-Inference Control Discussion Overall, results are consistent with the “Systems of Thought” hypothesis, though there were some surprises: The Predicted • Each cultural group strongly exhibited their expected cognitive bias in interpreting the behavior of protagonists in a story: • East Asian participants focused on contextual, relational, and holistic information (the field) – even when dispositional information was readily available. • Western participants made more descriptiveanalytic, subject-oriented inferences – even when situational information was easily accessible. The Surprising • Each group made more types of inferences than predicted by a strict interpretation of the Systems of Thought hypothesis: • East Asians made logical inferences • Westerners made situational inferences. Table 2 Inference Text Tony was trying desperately to stick to his diet. “Well,” said his mother, “You can have either bread or corn flakes with breakfast.” Tony seemed to take forever before giving an answer. “Alright Ma, since I have to skip something, I won’t have the corn flakes.” No- Inference Text Tony was trying desperately to stick to his diet. “Well,” said his mother, “You can have either bread or corn flakes with breakfast.” Tony seemed to take forever before giving an answer. He wondered if he could talk her into more helpings of corn flakes. More on the Surprises • That East Asians made logical inferences is not surprising from the perspective of psychological models of deduction (e.g., Braine & O’Brien, 1998; Lea et al., 1990; Rips, 1994). Final Summary • The hypothesis that culture affects cognition received partial support. • The strongest supporting evidence came from Western readers showing a strong dispositional bias, and East Asian readers exhibiting a comparably strong situational bias. • Evidence of Western readers making situational inferences is not well supported in the literature. Lupfer et al. (1990) found that situational cues helped participants recall the situational passages. However, they were not able to find on-line (priming) evidence for their spontaneous activation. • Some of the results that were inconsistent with the Systems of Thought hypothesis will require further work to interpret with respect to that hypothesis. • Perhaps the most surprising result is that Westerners activated both situation- and traitrelated concepts while reading the situational passages. An off-line follow-up study in which readers think-aloud while reading might clarify this result. • Our data clearly refute any claim that East Asians do not make propositional-logic inferences during everyday activities like reading. Table 3 Example Logical Text Probe: BREAD Western East Asian Population • Made situational inferences during both situation and trait texts • Even when a passage focused causality on the protagonist these readers activated situational concepts. • There was no evidence that they activated trait-inferences during the reading of any of our passages. • The Eastern readers made logical inferences while reading. Condition Example Trait, Situational and Control Texts 916 882 600 Results Summary Materials & Procedure • Participants read a block of 96 four-line texts one line at a time on a computer screen. • Passages ended with a lexical decision probe, and a comprehension question. • The 96 passages were composed of: • 16 pragmatic (trait & situational) passages • 16 pragmatic controls • 12 logic passages in their “inference” form • 12 logic passages in their “no-inference” form • 40 filler passages 838 Trait Inference Trait NoInference Control Trait Baseline Control Situational Inference Situational No-Inference Control Situational Baseline Control Control Passage Type Trait Situational Control Situational Trait Probe Type Trait Trait Trait Situational Situational References 6 2 4 Situational Logic Inference Logic NoInference Control Inference NoInference Logical Logical 247 presses 35 1 Braine, M.D.S., & O’Brien, D.P. (1998). Mental Logic. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Lea, R.B., O'Brien, D.P., Fisch, S.M., Noveck, I.A., & Braine, M.D.S. (1990). Predicting propositional logic inferences in text comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 361-387. Lea, R. B. (1995). On-Line evidence for elaborative logical inferences in text. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21, 1469-1482. Lea, R.B., Mulligan, E.J., & Walton, J. (2005). Accessing distant premise information: How memory feeds reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition, 28, 303-317. Lupfer, M.B., Clark, L.F., & Hutcherson, H.W. (1990). Impact of context on spontaneous trait and situational attributions. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 58, 239-249. Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. PsychologicalReview, 108, 291–310. Rips, L.J. (1994). The psychology of proof: Deductive reasoning in human thinking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Winter, L., & Uleman, J. S. (1984). When are social judgments made? Evidence for the spontaneousness of trait inferences. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 47, 237-252. Uleman, J., Hon, A., Roman, R., & Moskowitz, G., (1995). On-line evidence for spontaneous trait inferences at encoding. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.