DNRSimple document helps us take charge of our deaths.doc

advertisement

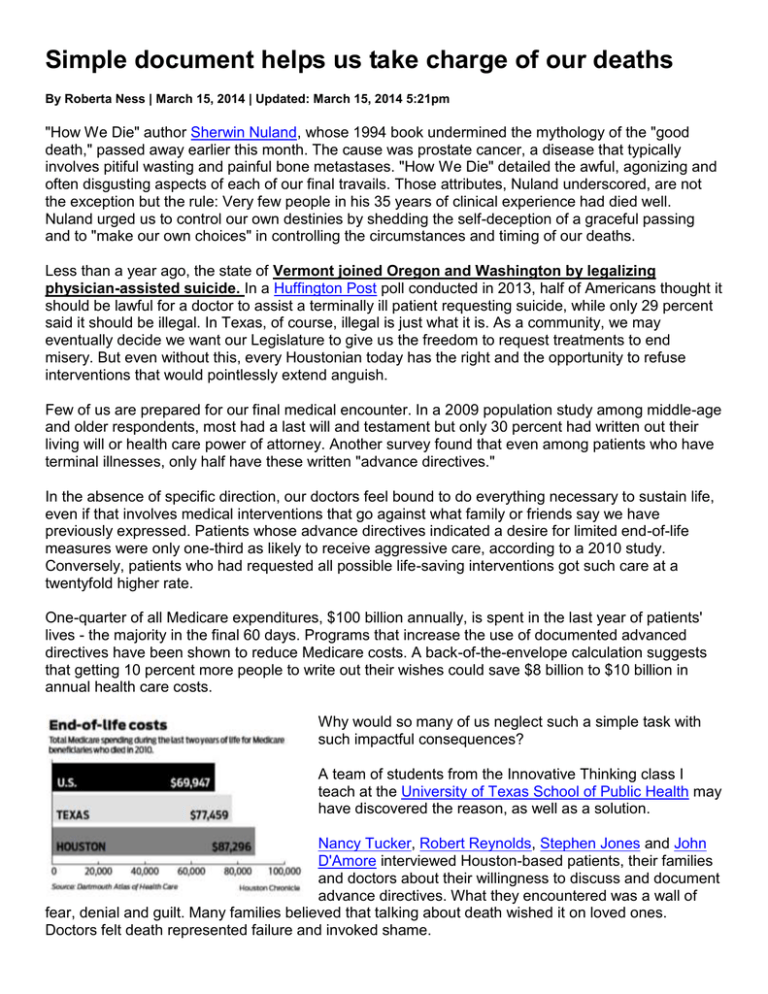

Simple document helps us take charge of our deaths By Roberta Ness | March 15, 2014 | Updated: March 15, 2014 5:21pm "How We Die" author Sherwin Nuland, whose 1994 book undermined the mythology of the "good death," passed away earlier this month. The cause was prostate cancer, a disease that typically involves pitiful wasting and painful bone metastases. "How We Die" detailed the awful, agonizing and often disgusting aspects of each of our final travails. Those attributes, Nuland underscored, are not the exception but the rule: Very few people in his 35 years of clinical experience had died well. Nuland urged us to control our own destinies by shedding the self-deception of a graceful passing and to "make our own choices" in controlling the circumstances and timing of our deaths. Less than a year ago, the state of Vermont joined Oregon and Washington by legalizing physician-assisted suicide. In a Huffington Post poll conducted in 2013, half of Americans thought it should be lawful for a doctor to assist a terminally ill patient requesting suicide, while only 29 percent said it should be illegal. In Texas, of course, illegal is just what it is. As a community, we may eventually decide we want our Legislature to give us the freedom to request treatments to end misery. But even without this, every Houstonian today has the right and the opportunity to refuse interventions that would pointlessly extend anguish. Few of us are prepared for our final medical encounter. In a 2009 population study among middle-age and older respondents, most had a last will and testament but only 30 percent had written out their living will or health care power of attorney. Another survey found that even among patients who have terminal illnesses, only half have these written "advance directives." In the absence of specific direction, our doctors feel bound to do everything necessary to sustain life, even if that involves medical interventions that go against what family or friends say we have previously expressed. Patients whose advance directives indicated a desire for limited end-of-life measures were only one-third as likely to receive aggressive care, according to a 2010 study. Conversely, patients who had requested all possible life-saving interventions got such care at a twentyfold higher rate. One-quarter of all Medicare expenditures, $100 billion annually, is spent in the last year of patients' lives - the majority in the final 60 days. Programs that increase the use of documented advanced directives have been shown to reduce Medicare costs. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that getting 10 percent more people to write out their wishes could save $8 billion to $10 billion in annual health care costs. Why would so many of us neglect such a simple task with such impactful consequences? A team of students from the Innovative Thinking class I teach at the University of Texas School of Public Health may have discovered the reason, as well as a solution. Nancy Tucker, Robert Reynolds, Stephen Jones and John D'Amore interviewed Houston-based patients, their families and doctors about their willingness to discuss and document advance directives. What they encountered was a wall of fear, denial and guilt. Many families believed that talking about death wished it on loved ones. Doctors felt death represented failure and invoked shame. The students mused: What if death was not equated to callousness or incompetence but to the inevitable? Perhaps Ben Franklin got it right when he said, "Nothing in life is sure except death and taxes" - and this maxim led them to a solution. Here's how it would work. A form would be offered at the time of hospitalization, along with consent and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) forms. Or the form could even be mailed out every year by the U.S. government, looking much like a tax form. Either way, easy-to-use check-off boxes would be there for intubation, force-feeding, resuscitation, etc., each elected (or not) under various circumstances. Updates could be made at every admission, or annually with tax submission. Rebates could even be offered for completing the advanced directive form. Discussions of death (and taxes) are always controversial. An early version of the Affordable Care Act proposed an incentive to physicians to discuss end-of-life care. Reframed by some in Texas as "Death Panels," the rider was quickly removed. Perhaps we have gotten beyond this and can instead get behind the idea of completing advance directives as a bureaucratic obligation. Meanwhile, a quick Internet search brings up forms that allow us to write out preferences for the end of life. We Texans pride ourselves on being independent thinkers and self-starters. Nuland left us an enduring gift - the advice to take charge of our deaths just as we take charge of our lives. Ness is dean and M. David Low Chair in Public Health at the University of Texas School of Public Health.