Hamlet.doc

advertisement

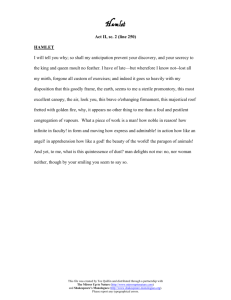

Hamlet 1 Hamlet Final exam questions: Give examples of how the disruption of the state, the family, and the individual are represented in Hamlet. Why doesn’t Hamlet carry out his revenge on Claudius sooner? The play represents “the problem of what to believe and the problem of how to act” ( Harry Levin, Shakespeare: Modern Critical Views, ed. Bloom, 59). Themes Reality vs. Illusion: ( one can argue that Hamlet’s discovery of the difference between the two so disillusions him that his will is paralyzed). The nature of humanity: angel, or base, corrupted beast? (Medieval/Renaissance idea is that man is the midway point, can go either direction). Revenge: Hamlet’s and Laertes’. Disintegration: a world going to pieces. Corruption: the corrupted world of the individual and the political gives rise to Hamlet’s doubt and hesitation and contributes to his belief in the apparent uselessness of action. Action is meaningless in a world that lacks standards of proper behavior that lacks a clear vision of what is good and what is evil. Hamlet sees the macrocosm in the microcosm; he universalizes each situation he confronts. For example, Hamlet Sr. represents all that is good to Hamlet. When his mother marries Claudius, all of Hamlet’s standards of good are thrown into confusion, and he begins to question everything: --counselors who are supposed to be wise (Polonius) --woman’s love ( his mother and Ophelia) --friendships (Rosencranz and Guildenstern) --the general nature of humanity (“What a piece of work is a man”) Hamlet 2 Theme of a world out of balance: “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” (I, iv, 90). “. . . this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire—why, it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors” (I, ii). “How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable Seem to me all the uses of this world! Fie on’t, ah, fie, ‘tis an unweeded garden That grow to seed. Things rank and gross in nature Possess it merely” (I, ii). Handbook, p. 112: As we have observed, Hamlet’s overriding concern, even before he knows of the ghost’s appearance, is the frustration of living in a world attuned to imperfection. He sees, wherever he looks, the pervasive blight in nature, especially human nature. Man, outwardly the acme of creation, is susceptible to “some vicious mole of nature,” and no matter how virtuous he otherwise may be, the “dram of evil” or the “stamp of one defect” adulterates nobility (I, iv). Hamlet finds that “one may smile and smile, and be a villain” (I, v). “What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and meaning how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god: the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals! And yet to me what is this quintessence of dust? (II, ii). The issue of action: “To be, or not to be” The ghost: Hamlet learns of his father’s murder from a ghost; but is it really his father’s ghost? “The spirit that I have seen/ May be a devil, and the devil hath power/ T’assume a pleasing shape, yea, and perhaps/ Out of my weakness and my melancholy,/ As he is very potent with such spirits,/ Abuses me to damn me” (II, ii). If the spirit is sent to trick him, he may end up killing an innocent man. Revenge: the revenge tradition demands that one must destroy one’s foe, the foe must know who it is that is taking revenge, and the victim, ideally, should be killed unrepentant so that his soul will go to hell, or at least to purgatory. Hamlet finds Claudius alone, praying: “Now might I do it pat, now ‘a is a-praying--/ And now I’ll do’t, and so ‘a goes to heaven,/ And so am I revenged. That would be scanned:/ A villain kills my father, and for Hamlet 3 that/ I his sole son do this same villain send/ To heaven./ Why this is bait and salary, not revenge” (III, iii) “Up, sword, and know thou a more horrid hent,/ When he is drunk asleep, or in his rage,/ Or in th’incestuous pleasure of his bed,/ At game, a-swearing, or about some act/ That has no relish of salvation in’t,/ Then trip him that his heels may kick at heaven,/ And that his soul may be a damned and black/ As hell whereto he goes” (III, iii). Contrast: the Classic Hero world vs. the Christian Handbook, p. 40-1: The Greek hero lives in a universe with finite horizons: he knows that he is mortal and that death offers at most an existence as a bloodless shade, and existence to which life on earth even as a slave is preferable . . .” Hamlet, by contrast, living in the modern Christian world, believes that his soul is immortal (I, iv, 65-8). . . . In fact, it is remarkable how many of the complications of Hamlet’s situation can be traced to the impact his belief in an afterlife has on his thinking . . . . [The classical hero’s ethic] virtually mandates suicide for a noble man under certain circumstances [for ex., when dishonor or disgrace are the alternative], whereas Hamlet’s forbids it under any circumstances.” Aspects of Hamlet’s worldview which work against his heroic impulses: 1. Heroic action begins to lose some of its luster when viewed from the perspective of eternity. 2. For all his admiration for classical antiquity, Hamlet has a distinctly Christian sense of the transiency of the glory of the ancient world. 3. He is very cosmopolitan—he finds it difficult to take Denmark and Danish affairs seriously, and is less likely to believe it worthwhile to “save” Denmark from Claudius. 4. Hamlet’s contemptus mundi attitude: Unlike a classical hero, he does not feel at home in this world. Far from believing that this world is all that man has, he is haunted by visions of a world beyond. 5. “. . . unlike a classical hero, Hamlet has a brooding sense that the appearances of this world conceal a deeper reality. That is why the world is so much more mysterious to him than it is to Achilles or Aeneas. He lives in a world in which the truth seems covered by veil after veil, and in which men must resort to devious methods to spy it out. . . Hamlet’s disillusioning experiences—especially watching his mother betray the memory of his father—have led him to mistrust appearances.