Document 15272524

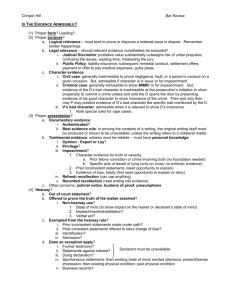

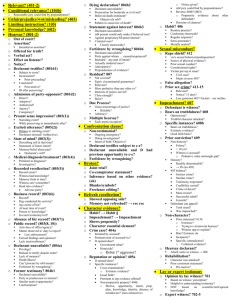

advertisement