1 Reasonableness Clause

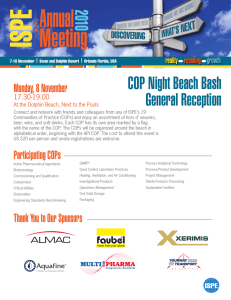

advertisement