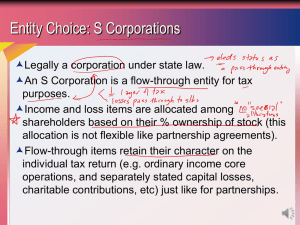

Corporations Outline – Scott 2007 Michael Petrocelli I.

advertisement