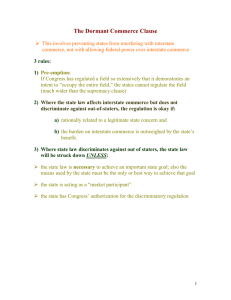

Spring 2008 – 2L Con Law, Rodriguez a. General

advertisement