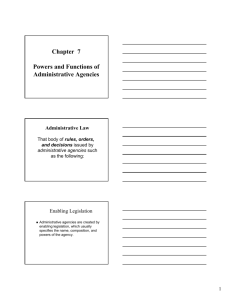

I. Separation of powers

advertisement