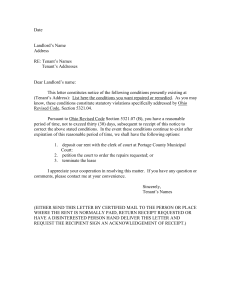

PROPERTY

advertisement