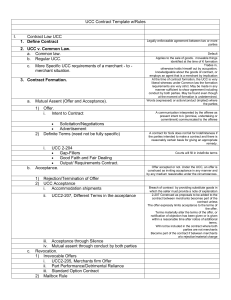

OVERVIEW Goals and benefits of contracts Efficiency

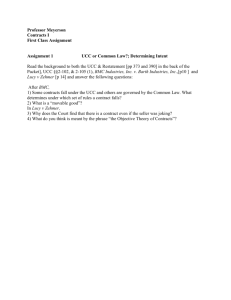

advertisement