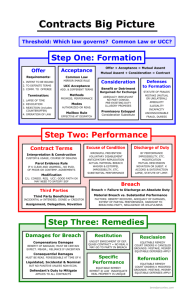

Contract Law Remedies: Expectancy & Limitations

advertisement