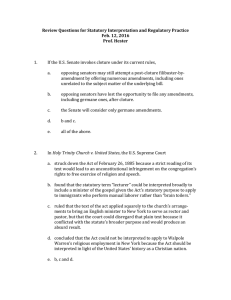

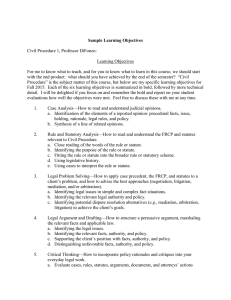

Administrative and Regulatory State (ARS) Outline – Rascoff, Spring 2009 –... I. Overview of the Regulatory State and Statutory Implementation and...

advertisement