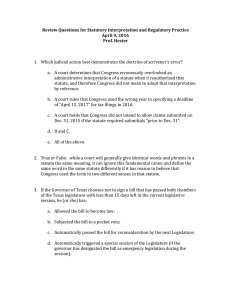

The Administrative and Regulatory State I. Basic Agency Framework

advertisement