TEACHING WITHOUT TOOLS: A CASE STUDY OF PART-TIME FACULTY

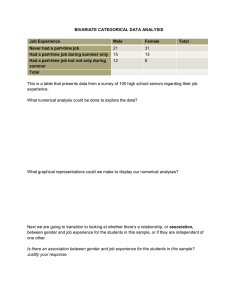

advertisement