SETE Recommendations

advertisement

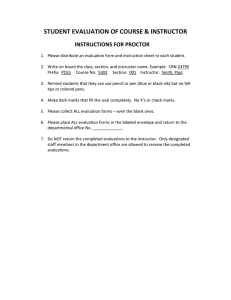

Recommendations from the Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching April 24, 2012 Executive Summary Provost Liz Grobsmith charged the Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching to explore current NAU practices in relation to the evaluation of teaching and best practices in other institutions and to make recommendations for Northern Arizona University. The recommendations are summarized below. At its core, the evaluation of teaching is conducted to ensure a positive and productive learning experience for our students, while helping to develop the effectiveness of those who teach. To establish a teaching evaluation system that preserves this perspective, the Task Force recommends a framework that invites units to explore reasonable means of gathering relevant data from multiple sources for effective evaluations. The Task Force further recommends the following practices in relation to student opinion surveys (questionnaires): Clarify the purpose and uses of course questionnaires for students; Administer strategic mid-term evaluations (as determined by units) that are more comprehensive, in conjunction with brief end-of-course questionnaires; Adopt a web-based tool (we recommend SmarterSurveys be piloted as the most promising option) for student opinion surveys for the following reasons: o Enhanced reliability o Meaningful comparisons (within and beyond NAU) o Ease of administration and analysis o Integration with the Faculty Activity and Achievement Reporting (FAAR) system The Task Force recommends the following in relation to the role of student success. At the unit level (department or program): Articulate clear expectations for student success (represented, in part, by the proportion of students achieving better than a D, F, or W in a course); Use data related to student success to determine the appropriateness of the course design and curricular placement; Use data related to student success to determine the appropriateness of the course assignments to instructors and the development of faculty; Incorporate context-sensitive judgments about teaching quality vis-à-vis student success data for individual faculty members. Recommendations from the Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching April 24, 2012 Introduction Provost Liz Grobsmith charged the Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching to explore current NAU practices in relation to the evaluation of teaching and best practices in other institutions, in order to make recommendations for Northern Arizona University. This document provides the requested recommendations. The charge from the Provost (September, 2011), summarized briefly, included the following issues: Explore alternatives to the current course evaluation practices at NAU, and Propose revisions to the system, procedures and instruments in place at NAU. Task Force membership: Kathy Bohan, ACC, COE David Boyce, GSG Wendy Campione, Teaching Academy, FCB Ryan Ellis Lee, ASNAU Gae Johnson, Faculty Senate, COE Dan Kain, Provost’s Office and Convener Karen Mueller, CHHS Mary Reid, President’s Distinguished Teaching Fellows, CEFNS Michael Vincent, Deans and PALC, CAL Andy Walters, SBS Eric Yordy, AADR, FCB The Task Force met monthly throughout the AY2011-12 year, through April. In addition, three subcommittees (Current Practices, Best Practices, and Common Procedures, Practices and Instruments) met regularly. Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 2 Recommendations of the Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching April 24, 2012 Purpose and Goals of Evaluation of Teaching The Task Force agrees that a system for evaluating teaching must address multiple purposes and goals. At its core, the evaluation of teaching is conducted to ensure a positive and productive learning experience for our students, while helping to develop the effectiveness of those who teach. However, within that overarching purpose, an effective evaluation system should also accomplish the following goals: To provide faculty members with direct and helpful feedback about the effects of their efforts to help students learn and to be successful; To provide information that will assist faculty members with opportunities for developing their skills as teachers; To provide faculty reviewers with valid and reliable information about teaching performance for decision-making in formal review processes; To ensure that students are active participants in the enhancement of teaching at NAU; To include faculty members as partners in their own evaluation process. General Principles for Evaluation of Teaching In recognition of the emphasis on excellent teaching at Northern Arizona University, the Task Force endorses a perspective on evaluation of teaching that is supportive, formative, and developmental. The Task Force encourages a system of evaluation that provides faculty members with direct feedback on the effects of their instructional/teaching efforts as well as opportunities to continue to grow as teachers throughout their careers. The act of teaching centers on an interaction that enables students to be successful in acquiring knowledge, skills, and dispositions (e.g., openness to diversity). The Task Force endorses a perspective on the evaluation of teaching that derives from sound principles that have emerged in the field of higher education. These principles are articulated, in brief, below: Effective evaluation is embedded in a process that is supportive of the growth and development of faculty members. While it is appropriate to make judgments about teaching quality, the starting point of effective evaluation is the recognition that evaluation is part of a system of support and opportunities for growth. Evaluation of teaching must recognize the contextual variation inherent in teaching at a large and multi-faceted university. Thus, any evaluation process must adapt to variations in that context. Principles of learning should inform evaluation processes. (See Appendix A for sample principles). Effective evaluation of teaching draws on multiple forms of evidence. Thus, it is appropriate for the evaluation of teaching to incorporate different forms and sources of evidence (see below). Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 3 Effective evaluation of teaching can occur any time in the second half of a course, and the blend of mid-term and end-of-term student opinion surveys can provide information needed by different participants in the process. To the extent possible, effective evaluation should honor the time commitments and perspectives of those called on to provide information. Thus, for example, consideration should be given to the demands placed on students in evaluating multiple instructors. Effective evaluation involves a systematic process of informing faculty, their peers, and administrators of the areas for growth, as well as areas of strength. The Role of Student Success in Evaluation of Teaching The Task Force considered the role of student success (represented, in part, by the rate of students achieving better than a D, F, or W in a course) in evaluating teaching. The Task Force does not endorse a specific percent of students achieving above the DFW level as a uniform measure of student success. We recognize that variables related to the course content, the decisions of students about taking particular courses, and the requirement status of courses (i.e., required vs. elective) all affect this issue. However, the Task Force does endorse unit-level consideration of student success as one component of the evaluation process. The following considerations are offered as questions for the units to consider in making judgments: What are appropriate indicators of student success for a particular program? In relation to course grades, what level of success does a department or program expect in the various courses (e.g., is 80% better than DFW acceptable?)? This should be articulated. For cases where the proportion of students succeeding is below the unit expectations: Is the course properly situated in the curriculum so that students have necessary prerequisite knowledge and skills to be successful? (Should the curriculum be revised?) Are students enrolling inappropriately so that they are not academically and/or developmentally prepared for the course? Is the low student success a part of a pattern (for the particular students, the course, the instructor, something else)? Does the instructor’s teaching assignment match his or her teaching strengths and interests? What explanation does the instructor provide for levels of success that are under unit expectations? What actions has the instructor taken to enhance the success of students? Ultimately, the Task Force recommends that units establish clear expectations both for acceptable student success and also for inclusion of this factor in making judgments about teaching. Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 4 Framework for Data Gathering Assuming the value of multiple forms and sources of evidence, the Task Force recommends the following framework, based on Arreola (2000) and Felder and Brent (2004)1, for gathering data from appropriate sources in order to provide a balanced view of evaluation. Additional information about the sources of data and data-gathering processes is included in Appendix B. Arreola, R.A. (2000). Developing a comprehensive faculty evaluation system: A handbook for college faculty and administrators on designing and operating a comprehensive faculty evaluation system (2nd ed.). Bolton, MA: Anker. Felder, R.M. and Brent, R. (2004) How to evaluate teaching. Chemical Engineering Education, 38(3), 200-202. 1 Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 5 FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING TEACHING (After Arreola, 2000, and Felder & Brent, 2004) Summary of salient criteria for teaching evaluation, the appropriateness of each evaluator group (faculty member, students, peers, chair/director) for evaluating these criteria (N/A = not appropriate), and the technique for evaluation. Main evaluator for each criterion shown in bold. Activities, questions, and conditions of use for each evaluator addressed in Task Force Report Appendix B. Criteria Content Expertise Instructional Delivery Sub-Criteria Analysis of content expertise Perceptions of instructor’s content expertise Effectiveness of delivery Student success Instructional Design Skill Analysis of instructional design Perceptions about course design Course Management Evaluator Faculty Member Assesses ongoing development of content expertise Team teaching, peer assessment, teaching scholarship Describes philosophy and methods; (video selfassessment possible) Describes efforts to ensure student success Describes philosophy and approach Describes course objectives, outcomes and measures Describes philosophy and methods Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 Students N/A Peers Review course materials Chair/Director Reviews course materials Evaluate instructor via questionnaire N/A N/A Evaluate instructor via questionnaire (Review videotape if available) N/A Evaluate instructor via questionnaire Review DFW rates and explanation in concert with departmental indicators Review course materials Reviews DFW rates and explanation in concert with departmental indicators Reviews course materials Evaluate instructor via questionnaire N/A N/A Evaluate instructor via questionnaire Review course materials Reviews course administration materials and student feedback N/A 6 The Task Force recommends that units explore reasonable means of gathering relevant data from multiple sources for effective evaluations. However, the Task Force was specifically charged with determining whether to recommend any common procedures and/or items for student opinion surveys. To that end, the following recommendations are offered: Questionnaires for Student Evaluations (Student Opinion Surveys) A key element in the matrix presented above involves questionnaires or student opinion surveys. The Task Force recommends the following universitywide procedures: Clarify the Purpose of Evaluations Research demonstrates that the nature of student responses varies according to their understanding of the purposes and uses of course evaluations. Therefore, it is incumbent upon units and faculty members to communicate the value and uses of the information gathered through the evaluation process. Midterm and End-of-Term Questionnaires Using both midterm and end-of-term questionnaires is a promising practice for several reasons, as enumerated below. The use of a two-stage process may diminish the time demands placed on students at the end of the term; provides faculty an opportunity to incorporate valid suggestions into their courses while the providers of that feedback can experience the changes; offers the possibility of more individualized and substantive feedback for faculty members; forms a reasonable approach to distinguish the uses of evaluation material (for example, a midterm questionnaire might be used in the year of comprehensive reviews for tenured faculty members, but not in expedited review years); and allows for streamlining the final course evaluation process, potentially increasing the likelihood of student participation. Therefore, the Task Force recommends a unit-determined approach of blending more comprehensive midterm evaluation forms with brief end-of-term questionnaires. Commercial vs. “Home-grown” Surveys The Task Force recommends NAU use a commercial provider to administer the student opinion surveys. This approach will enable several advantages: comparability among units, uniformity in the administration of surveys, enhanced reliability of survey data, reduction of staffing demands within NAU, flexibility in the development of midterm survey items and integration with the Faculty Activity and Achievement Report (FAAR) system. The collection of reliable data with opportunities for comparisons provides departments with a tool to enhance unit effectiveness. We recommend the use of SmarterSurveys. The advantage of the Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 7 services offered by SmarterSurveys include the following: single price for the year, regardless of the number of surveys administered; flexibility in constructing instruments to meet the needs of various units; and integration with the Faculty Activity and Achievement Reporting (FAAR) system. The Task Force recommends the tool be piloted in AY2012-13. Results of the pilot experience will be incorporated into the decision-making process. Common Items in End of Term Questionnaires The Task Force endorses a small set of common items for end-of-term evaluation forms. These items are the components of the SETE (Student Evaluation of Teaching Effectiveness), provided through SmarterSurveys (www.smartersurveys.com). Administering Surveys The Task Force endorses the administering of surveys via a web protocol. We recognize that there are legitimate concerns about the response rates for student questionnaires. Several practices tend to lead to higher response rates, and we encourage units to explore how best to incorporate the following: Students are more likely to respond if they are convinced the information is put to use (both by faculty members and by administrators). Therefore, communication about the uses of course evaluations must be proactive. Students are more likely to respond if the end-of-term evaluations are succinct and less demanding of their time. Students are more likely to respond if they are assured of anonymity. [Note: it is crucial that students understand that midterm evaluations will be read by instructors during the course.] The Task Force urges units to consider carefully the appropriateness of incentives (e.g., extra credit) that faculty members offer students for completing evaluations. Summary The Task Force recommendations are presented to the Provost, but we would urge broader discussion among key constituents, including the Provost’s Academic Leadership Council, the Academic Chairs Council, and the Faculty Senate. Key elements of our recommendations are as follows: Create an evaluation system that incorporates information used for formative as well as summative purposes, based on principles of effective teaching; Encourage units to gather and use multiple forms of evidence from multiple sources in evaluating teaching; Following a pilot in AY12-13, adopt a uniform web-based course evaluation system (assuming the pilot warrants this); Incorporate brief end-of-course surveys and mid-term surveys as appropriate to the purpose at hand; Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 8 Encourage communication with students to enhance participation and response rates. Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 9 Appendix A: Principles of Learning Created by the Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence of Carnegie Mellon University Available: http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/principles/learning.html Theory and Research-based Principles of Learning The following list presents the basic principles that underlie effective learning. These principles are distilled from research from a variety of disciplines. 1. Students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder learning. Students come into our courses with knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes gained in other courses and through daily life. As students bring this knowledge to bear in our classrooms, it influences how they filter and interpret what they are learning. If students’ prior knowledge is robust and accurate and activated at the appropriate time, it provides a strong foundation for building new knowledge. However, when knowledge is inert, insufficient for the task, activated inappropriately, or inaccurate, it can interfere with or impede new learning. 2. How students organize knowledge influences how they learn and apply what they know. Students naturally make connections between pieces of knowledge. When those connections form knowledge structures that are accurately and meaningfully organized, students are better able to retrieve and apply their knowledge effectively and efficiently. In contrast, when knowledge is connected in inaccurate or random ways, students can fail to retrieve or apply it appropriately. 3. Students’ motivation determines, directs, and sustains what they do to learn. As students enter college and gain greater autonomy over what, when, and how they study and learn, motivation plays a critical role in guiding the direction, intensity, persistence, and quality of the learning behaviors in which they engage. When students find positive value in a learning goal or activity, expect to successfully achieve a desired learning outcome, and perceive support from their environment, they are likely to be strongly motivated to learn. 4. To develop mastery, students must acquire component skills, practice integrating them, and know when to apply what they have learned. Students must develop not only the component skills and knowledge necessary to perform complex tasks, they must also practice combining and integrating them to develop greater fluency and automaticity. Finally, students must learn when and how to apply the skills and knowledge they learn. As instructors, it is important that we develop conscious awareness of these elements of mastery so as to help our students learn more effectively. 5. Goal-directed practice coupled with targeted feedback enhances the quality of students’ learning. Learning and performance are best fostered when students engage in practice that focuses on a specific goal or criterion, targets an appropriate level of challenge, and is of sufficient quantity and frequency to meet the performance criteria. Practice must be coupled with feedback that explicitly communicates about some aspect(s) of students’ performance relative to specific target criteria, provides information to help students progress in meeting those criteria, and is given at a time and frequency that allows it to be useful. Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 10 6. Students’ current level of development interacts with the social, emotional, and intellectual climate of the course to impact learning. Students are not only intellectual but also social and emotional beings, and they are still developing the full range of intellectual, social, and emotional skills. While we cannot control the developmental process, we can shape the intellectual, social, emotional, and physical aspects of classroom climate in developmentally appropriate ways. In fact, many studies have shown that the climate we create has implications for our students. A negative climate may impede learning and performance, but a positive climate can energize students’ learning. 7. To become self-directed learners, students must learn to monitor and adjust their approaches to learning. Learners may engage in a variety of metacognitive processes to monitor and control their learning—assessing the task at hand, evaluating their own strengths and weaknesses, planning their approach, applying and monitoring various strategies, and reflecting on the degree to which their current approach is working. Unfortunately, students tend not to engage in these processes naturally. When students develop the skills to engage these processes, they gain intellectual habits that not only improve their performance but also their effectiveness as learners. Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 11 Appendix B: Sources of Data and Data-collection Faculty member’s self evaluation General scope of topics for faculty member’s evaluation: What am I, as a faculty member, aspiring to accomplish in my teaching? How has my scholarly agenda enhanced the content, methods, and outcomes of my teaching? How have I sought to meet the varying needs of my students with respect to their level of understanding of the content I teach? How have I sought to develop a culturally affirming and respectful learning environment in the context of my teaching? How have I maintained my enthusiasm and engagement for my teaching? Faculty member: Reflects on their content expertise, their efforts to remain current, and their contributions to this content area Describes their philosophy of teaching and discusses their preferred methods of instruction Describes their philosophy for course design; also reflects on their course objectives and on how course materials are developed to meet those objectives and to maximize instructional impact Describes their philosophy of course management and as well as their general policies for successful course management Conditions for use: Needs skills (or guidance) in identifying goals and collecting appropriate data Must not be weighted highly in personnel decisions Student evaluations General topics for student input: What have students learned and how have they changed? How did teaching acts affect students? How did instructor’s actions affect students? What do students like or dislike about an instructor? Students evaluate (and sample questions): Their perceptions of a faculty member’s expertise The instructor seemed knowledgeable in the area of the course content. The instructor incorporated current material into the course. Instructional delivery (i.e., how well does the instructor create an environment which promotes and facilitates learning and how well did they communicate information, concepts, and attitudes? Does the instructor promote or facilitate learning by creating appropriate affective learning environment?) The instructor was receptive to the expression of student views. The instructor gave clear explanations to clarify concepts. The instructor found ways to help students answer their own questions. At times it was difficult to hear what the instructor was saying. Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 12 The instructor emphasizes conceptual understanding of the material. Remaining attentive in class was often quite difficult. The instructor did not seem to enjoy teaching. Their perceptions about course design The instructor made it clear how each topic fit into the course. This course enabled me to learn to apply course material (to improve thinking, problem solving, and decision). The instructor related course material to real life situations/ The instructor gave tests, projects, etc. that covered the most important points of the class. Rate the difficulty of this course. The grade I expect to receive accurately reflects my learning in this course. Course management The instructor gave timely feedback given course assignments and evaluations (e.g., examinations, reports, homework exercises, papers, projects, etc.). The instructor was available during office hours. Conditions for use: Ensure anonymity Clarify purpose of evaluations (i.e., distinguish that they are used for personnel decisions and not just for instructional improvement) Other notes: Student evaluations may be performed any time during the second half of the semester For post-tenure faculty, a total of 8 classes should be evaluated every 5 years and each course should be evaluated at least once. Peer evaluation: General scope of topics for peer evaluation input: Does teaching reflect currency in the content area of the courses taught by the faculty member? Does the course content reflect the appropriate level of rigor for the course level and subject matter? Do the modes of student engagement reflect utilization of research into how students learn and are they appropriate to the level of the course? Is there evidence that the faculty member has created an appropriate affective learning environment, one that is culturally affirming and respectful? Are there ways that a targeted mentoring process could develop and improve teaching effectiveness and resultant student learning? Examples of peer evaluations and their place in the faculty evaluations: Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 13 Summative evaluations should follow formative ones in the academic calendar so that faculty have greater opportunity and incentive to improve their teaching. Formative peer review should be treated as community property – shared by all – to assist both new and established faculty to improve teaching and student learning. Pressures beyond the academy seek greater responsibility and accountability for teaching – peer review is one way faculty can document what we do as teachers. Conditions for use of peer evaluation: Teaching should be considered and evaluated as a worthy scholarly endeavor – when it is reviewed by peer – in same fashion as research. How information is communicated is as important if not more important than the content. Problems in teaching must never be explicitly identified without accompanying alternative solutions. Formative evaluation is best if: One focuses on one or two specific behaviors or specific components such as test or texts. It is developmental not judgmental. Classroom visitation may be part of the process Classroom visit could be valuable for formative assessment and faculty development but should not be used for personnel decisions High degree of professional ethics and objectivity required on the part of the peer evaluators Requires training in observational and analysis skills Task Force on Evaluation of Teaching, April 2012 14