12599120_Reflexivity FINAL.doc (102.5Kb)

advertisement

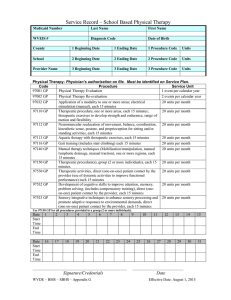

RUNNING HEAD: Reflexivity and Change Reflexivity, Reflection and the Change Process in Offender Work Andrew Frost Kia Marama Special Treatment Unit Marie Connolly University of Canterbury Key words: sex offending, therapeutic change, comprehensive process analysis 1 Abstract This study explores the therapeutic engagement experiences of men who have sexually offended against children and who are involved in a prototypical prison-based group treatment programme. The study examined factors relating to the therapeutic engagement of the offender in treatment, and in particular, the impact of the “out-of-group” time between sessions. The findings, while tentative, suggest that between formal therapy sessions, clients of the programme make significant movement either towards or away from engagement in the therapy. The implications of these processes with respect to clinical practice and the development of offender services are discussed. 2 Introduction Understanding how therapeutic change occurs is essential to the development of treatment services for men who have sexually offended against children. Attempts have been made to develop a general theory of change (Henry, 1999), and some 450 schools of psychotherapy have been identified (Kanfer & Schefft, 1988). Clearly there exists a considerable variety of models and applications of assisted planned personal change. Nevertheless, we might conclude from a transtheoretical view of the literature that an ideal context for deliberate change - that most likely to maximise opportunities for change to occur - will provide a number of facilitating features: an adequate “workspace” (Hubble, Duncan, & Miller, 1999) for the purposes of both the contemplation of change and the rehearsal of new practices; a climate within which trust and open expression is most likely to flourish; and the availability of new and challenging information so that novel experiences are possible. In this way a forum for experimental change is established, where those at various stages in the change process have the opportunity to try out alternative ways of thinking about their world and to test new possibilities for action. In addition, an optimal therapeutic environment will provide situational cues to action and reinforcement of outcomes that are considered desirable. In the ideal environment, a spirit of confidence and faith in the particular methodology offered inspires a hopeful attitude toward change outcomes. An important means of understanding the change process within therapy is advanced by the comprehensive process analysis (CPA) method (Elliott, 1989; Rennie & Toukmanian, 1992). CPA is a narrative research method that aims to better understand the essential mechanisms of client change. It is an approach that focuses: “on fine-grained process description of patterns in recurrent change episodes within specific contexts (that) can enable us to grasp the essential nature of the mechanisms leading to change, and thus to illuminate change across different therapeutic situations” (Rice & Greenberg, 1984:14). 3 Although process research has been defined as the study of the interaction between client and therapist systems both within and outside treatment sessions (Greenberg & Pinsoff, 1986), research has more generally focused on the change process within the context of the therapeutic session. In offender treatment services, much emphasis is placed on the significance and impact of the therapeutic group with regard to confronting issues of responsibility versus blame, openness versus concealment and collaboration versus collusion. Participants challenge each other within the group, and a culture of support provides a context for individual reflexivity and change. However, inevitably much of the offender’s time is spent outside the therapeutic session. If it is accepted that positive change is affected by the impact of within-group peer interaction, then it follows that out-of-group time is also likely to be of importance to the ways in which the men process their experiences from formal sessions. The current study looks specifically at the impact of out-of-group time within an offender treatment service. The research is influenced by the comprehensive process analysis method, and in particular, the qualitative research emerging from this approach (Rennie, 1992). The first phase of the research, which is reported elsewhere (Frost, in press), focused on in-session events and their impact on the process of therapeutic engagement with men who sexually offend against children. This phase of the research studied the responses of participants when faced with the requirement that they demonstrate openness and responsibility. Findings revealed four relatively distinct approaches. These approaches were called disclosure management styles and came to be labelled as exploratory, oppositional, evasive and placatory. They are described briefly here. The first of the approaches to managing disclosure, labelled the exploratory disclosure management style, was characterised by discoverydriven intentions and a reflective openness. Participants who exhibited a clear commitment to this investigative orientation actively sought collaboration with others, and demonstrated a considered response to feedback. 4 A second identified grouping of participants adopted a primarily oppositional focus. Their tendency was to view the therapy session as an adversarial encounter, in response to which they adopted a defensive or combative posture. These participants were inclined to describe their overall experience of the session in terms of embattlement. Not surprisingly, they remained generally unengaged throughout the session. Some participants exhibited a preoccupying vulnerability to emotional harm, and sought to minimise their exposure to the scrutiny of others throughout the index session. The management style in this case was labelled evasive. These men indicated ambivalence toward intervention and attempted to avoid negative evaluation throughout the therapy session, sometimes resorting to a range of subterfuges. At the peak of their discomfort, some of these men were apparently consumed by an urge to physically or symbolically escape from their predicament. Nevertheless, data also suggested clear potential for engaging these men. The last of these disclosure management styles involved a primary concern with securing the support of others. While typically maintaining an outwardly responsive and engaged approach, participants inclined toward this placatory mode of managing the therapy encounter consistently revealed that their principle intention was to convey an impression of openness. Such biasing often interfered with their attention to the explicit content of the session. The placatory style seems to be a response to a need to appear compliant. However, in this case also the data provided optimism with respect to positively engaging these participants. Emerging from this in-session analysis (phase one), the second phase of the study, reported here, examined the significance of the out-of-session behaviour on therapeutic engagement. The analysis, which now forms the basis of this paper, explores the period between therapeutic encounters. The findings, while tentative, suggest that between formal therapy sessions, clients of the programme make significant movement either towards or away from therapeutic engagement. 5 Method Research Participants Participants were incarcerated offenders convicted of one or more sexual crimes against persons under the age of 16. Prior to their inclusion in this study, each had volunteered for inclusion in the Kia Marama program, which is based in a stand-alone prison unit. The unit is housed at Rolleston Prison, a medium security facility within the Canterbury region of Aotearoa New Zealand. Over the course of the study, treatment groups were commencing every one to two months. Inmates accepted for treatment were transferred to Rolleston from regional prisons. Of the 16 primary participants, their ages ranged from 23 to 65 with a mean age of 40.2 (SD = 12.7). The convictions of this group involved indecent assault, unlawful sexual connection and sexual violation. Two were Maori and 14 were of Pakeha (non-Maori, generally European) ethnicity. Length of sentence ranged from 24 to 72 months, with the mean being 40.3 (SD = 14.8). Number of victims ranged between one and eight, with a mean of 2.75 (SD = 2.2). None of the primary participant group had a current psychiatric illness, although five had psychiatric histories. Procedure The research was undertaken at the Kia Marama Sex Offender Treatment Programme for adult males who have been convicted of child molestation. The study involved qualitative interviews with 16 male offenders undergoing group treatment. The interviews explored their experience of therapeutic engagement (Frost, in press), and also the significance of the out-of-group time between sessions. Here, the men referred to the impact of interpersonal encounters during group therapy, and to subsequent processing that gave rise to changed perceptions around material addressed in the group sessions. For some men the changes they described had led to consolidation of their initial responses to the therapy encounter, for others it had resulted in marked changes in their thinking. Hence, the interviews explored the men’s thinking that was directly related to the events of the session, and their subsequent processing of the session. With respect to the between-session period the 6 men were guided to explore: (1) Whether they thought about the sessions afterward, (2) Whether they could identify issues from the sessions and what meaning this had for them, (3) Whether they discussed the session with anybody afterward, and if they did, the circumstances surrounding the discussion, (4) Salient characteristics of their confidants, (5) The content of the interaction and its meaning for them, and (6) The outcome of the discussion, and their responses. Research participants were men who had undergone a group therapy session in which they were required to disclose and discuss details of the pattern and process of their offending. They were subsequently interviewed with respect to aspects of that session that they had experienced as especially salient. This was achieved by their viewing a video recording of their participation in the session and simultaneously articulating their thoughts relating to salient episodes. Thus an articulated thoughts paradigm was utilized (see Davison, Robins & Johnson, 1983). The disclosure management model (Frost, in press) was derived from an analysis of the within-session data. However, it became apparent at an early stage in collecting these data that participants were reporting significant experiences relating to engagement that occurred outside the formal therapy setting. That is to say, the experiences to which they referred took place in the period between the formal therapy and research process, and within the every-day prison domains. These experiences related to the participants’ further consideration of the events they had identified as salient. This often took place in the light of the "reality testing" that they felt was unavailable to them during the formal session. It was decided therefore to explore this clearly significant component of their experience. To this end, on the day following the index session, participants were additionally asked to reveal any thinking directly related to events of that session, and to recount the content of that thinking. This data was followed through in each case to the point where the participant exited from the process of engagement, as signified either by his dismissal of its relevance or his communication that he had resolved the issue raised. Analysis 7 The analysis of the interview data was influenced by the grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This approach involves the inductive derivation of theory from qualitative data using a sequence of coding procedures. Here, the researcher conducts the investigation and generates theory prior to consulting existing theories. Data are analysed as they are collected through the “constant comparative method”, which involves the systematic coding and categorisation of data until patterns begin to emerge. These low level descriptions must be checked for “fit” against the data. The initial unit of analysis comprises the smallest extracts from the data of which discrete sense can be made, such as a single phrase from a transcript. As analysis proceeds, concepts become increasingly abstract, and those relating to the same phenomena are grouped into higher level categories using the same (constant comparative) process. The focus then shifts to the relationships between categories, and a hierarchical structure is developed that captures these relationships. In this way an explanation of the phenomena under study can be proposed. As with the within-session material, the resulting transcript texts were initially broken down and divided into separate and discrete meaning units, as illustrated: “Not much happened during the session, apart from I felt anger and sadness and a lot of pressure on myself. / The impact came later, / because when I was with the group I thought my [offence] chain was clear, / by the time I finished it I was lost / and I got more help on my chain after my group from the guys outside. / I made more progress that night than I did for the whole morning. /” These meaning units were subsequently grouped into one or more categories and labelled according to theme. As this proceeded, the units were condensed into clusters at a higher level of abstraction to capture and combine categories of similar meaning. The process of collating categories was followed by preliminary attempts to plot potential relationships between them. Data continued to be assigned to categories as each data source was analysed. 8 The gradual nature of the data collection facilitated a process of analysis involving the alternate compressing and expanding of the data in a semantic sense. As the data were accumulated, hypothesized relationships between categories were postulated (compression), then the categories were “trialed” by re-opening the categories (expansion) in order to test the hypotheses for goodness of fit with the data themselves. New qualitative data was then collected according to the direction emerging from this processed data. In this way a process (reflexivity) and a sequence of sub-processes (recall, issue identification, rumination, consultation and reflection) were identified. Results Between formal therapy sessions, clients of the programme were found to make significant movement either towards or away from engagement in the therapy process. The analysis of the data supports the delineation of phases within a six-stage sequence. The model developed to depict these sequential stages is now presented (Figure1). Each emergent stage gives rise to the next, and at each stage there is the possibility of the man exiting from the process of ongoing engagement, at least temporarily. Advancing from one stage to the next in the sequence entails some active initiation on behalf of the offender. Passage through each stage involves the reprocessing of material that is experienced by the man as salient and recalled from the therapy session. Such reprocessing, we argue, presents the opportunity for therapeutic change as the individual seeks to make sense of events or experiences from the group session. Figure 1 HERE The phases of the model are now described in detail. Examples from the interview text are used to illustrate potential engagement or disengagement factors. 9 Stage 1: Recall from Session In fact all the participants in this study were able to recall material from the group session. In a strict sense then, this stage is a theoretical one and incorporates the notion that some of those undergoing this process would have nothing of significance to recall from that session. The empirical support for this notion is contained in the observation that some participants drew attention to experiences during the therapy session that interfered with their capacity to make useful sense of it. These experiences constituted, temporarily at least, impediments to taking on relevant information from the session. The intensity of these experiences resulted in confusion for these men and the impoverishment of their cognitive processing. Some indicated that following the session, they felt too distressed or disoriented to be able to complete a simple recall task, which was a requirement for participants of the study: “I didn’t get to say anything on the [recall] tape. I was really upset and angry, I felt as if I didn’t come across very well. I had to - I felt as if I was being misunderstood. I think I was being misunderstood in what I was saying. It was anger, frustration and deep depression - deep, deep depression. I didn’t know whether I was coming or going.” It is hypothetically possible then that for some clients undertaking this component of the therapy programme, no significant experience is recalled from the session. This represents, theoretically at least, the first possibility for departure from an ongoing process of engagement. The content from the session that survives for recall becomes available for reprocessing. The client is in a position to review his perceptions of this material and its implications for him. Stage 2: Issue Identification “Issues” are defined here as matters perceived by the individual to require attention of some sort. The issue or issues create an internal tension for him, and an increased motivation to address the tension indicates a 10 positive engagement in the therapeutic process. Two of the men in the study “disengaged” at this stage. Both of these participants were identified in the first part of the study as exhibiting a predominantly oppositional disclosure management style. Each of the other thirteen participants identified at least one issue from the therapy session of remaining concern to him. These were matters privileged for recall for some reason and subsequently addressed by him in some way. Some of the issues identified were clearly articulated: “What has been on my mind was a lot about my wife, about myself; how I had treated her, how she treated me.” Others reflected complex analysis of the issues: “…I thought most about the questions and answers. Particularly about me being a bully. And that stuck in my mind. I [originally] thought I was more over-bearing, seeing as I was the oldest. There were three of them when I was young. Well, I didn’t get on well with my father, he more kept to himself than he did with me. I tried to make it up with my son and my daughter.” Those two men who were unable or unprepared to identify issues from the group session apparently experienced no internal tension. In the absence of this tension, these men were seen to opt out of the engagement process at this stage: “Nothing stands out for me about the session yesterday”. Hence, the capacity of participants to identify and engage with the internal tension generated from the recalled session became a clear factor in their therapeutic engagement or disengagement at this stage of the out-ofgroup process. Stage 3: Rumination This stage refers to the individual’s inclination to allocate cognitive resources to the issues he has identified, and his emotional response to the 11 process and outcome. That is to say, it involves his independent engagement in teasing out those issues, and his pondering, puzzling or even agonising about them: “I did have a cry at tea break yesterday, I was pretty emotional. What brought that about, was shame, remorse, about what I done; the effects….I have been non-stop thinking about why I offended. I think I was stuck in a childhood way of myself. I was always stuck, in a way, all my life and didn’t really realise. That I haven’t grown up.” Twelve of the men in the study went on to engage in this process. A key dimension within the content of the man’s ruminating was identified as affect function. This refers to the apparent role of revealed emotion. For some men their feelings around the identified issue served as a form of escape from tension. Rumination motivated in this way appears to divert participants away from genuine engagement: “He [Therapist] was going back to where I had a - when I was molested as a kid. He expects me to be able to tell him how I felt when I was seven or eight, or however old I was. I couldn’t even tell you exactly how old I was; how can I think back that far? - No idea! I put it back onto him, I said ten years ago, what did you get for your birthday - end of story! After the session, I didn’t think any more of that. No. Closed the book; put it behind me - end of the day!” For those whose emotional response to an issue is associated with a felt need to engage with the feeling, the resulting tension indicates a link to further processing, and maintained engagement: “[pause] When I think now about the session, I felt as if what was said was putting a lot of blame on [victim]. I was putting the blame on her. I thought, “I admitted that; I confessed it in court.” But I feel that I’m trying to say that because she came into my bed - that it justified me from then on. I feel that is the impression I am giving. Because it seems that unbelievable that I did it. When I think about it - it doesn’t feel right.” 12 At some stage in this process, depending it seems on the direction and dimensions of his ruminations, the man may foreclose on the issue, and put it aside. “I was starting to think about it last night. I ran it through what I was feeling, I wrote some down but - what the hell! - I threw it in the rubbish tin. I just thought: ‘No!’ This latter outcome marks a further potential point of departure from an uninterrupted process of engagement. Stage 4: Consultation This stage is likely to be reached by clients whose motivation is inspired by self-enquiry, fear of unfavourable evaluation by others, an urge to be understood by or affiliated with others, or by some combination of these factors. In other words most of the men characterised by exploratory, placatory and, interestingly, evasive disclosure management styles went on to consult with others on matters related to their experience of the disclosure encounter. In all, ten of the 16 men in the study undertook a process of consultation with others within the prison unit. Here, a matter of personal significance is referred to others, marking a key point in the process of engagement as the identified issue passes from being merely the subject of individual rumination and becomes amenable to intersubjective scrutiny. In other words, it passes from the personal to the interpersonal. “I needed to clarify things, it helps talking about your problems - for feedback. You get a better picture of the situation, rather than milling it over by yourself. And possibly your thoughts might be wrong, and the feedback helps you understand.” Clients were motivated to seek out the most propitious or expedient combination of persons and conditions (timing, location, and readiness) 13 relevant to the needs established and revealed in their individual deliberation (Stage 3 “rumination”). In these ways, consultation can be seen to take place in a distinguishing context: “Yesterday, it was hard to listen to people. Today, it was - I was listening to R. He was listening to me, he was telling me. I was telling him how I felt, that how [Victim] came to into my bed the very first time. And he brought to my attention what happened before that….” “The next morning I talked to S, that clarified things for me. I spoke to him. That was amazing. My opinion of him was that he was a fuck-wit and a loudmouth: he was an adult child in his actions and the way he behaved - and yet here was a man.” There are striking and important common features across these contexts in which clients seek consultation. Important factors are: Reciprocity: a faith in mutual self-help: “Apart from more confidence, It made me more open and honest talking about my offending - more comfortable. It was the fact that they were pretty open and honest with me about saying things and I thought I would be the same.” Interpersonal congruence: a recognition of complementary qualities in certain others: “I actually thought that, um, I feel that they want to help me and I want to help them. That is the main thing, we want to help each other, I think us three more or less work together quite a bit and we talk about things quite good.” The provision of personal support and respectful, reflective discussion: “I talked to some of the other guys, in terms of what I was angry about - those things where [Therapist] cut me off. That changed when I talked to the other 14 guys, especially when I talked to J - that was good. Then I talked to C. I talked to him about the abuse side and that brought in the [offence] chain as well.” Personally safe environments: “I felt confused about [my] father. When I went and started talking with D…we were the only two left in the dining room. I went over and sat next to him, then we began talking about – ’cause he said sorry about fronting me up about the feelings about my father. He obviously saw that there were angry feelings, and that he was sorry that he had brought them up. And it was mainly just to talk about - hey - they were going to come up at some stage, and better sooner than later. So he knew how things were going down for me.” It was typical for participants to approach a range of others who offered both intellectual reflections on identified discrepancies in their understanding as well as emotional support to assist them in facing up to disclosure: “I would say, that J is more of an intellectual than G is. G is good to be with but he is not as intellectual as J is. G was more supportive as a friend.” In contrast to such common features, there are telling distinctions across the particular functions and qualities of consultants sought by clients. Interestingly again, the functions and qualities looked for appear to vary according to the particular disclosure management style of the man consulting. The response from one man whose approach was characterised by a placatory style indicates a concern with repairing perceived damage to a relationship and smoothing over conflict: “I spent just a couple of minutes talking to him, the older guy. He just told me that what I had put down on the chain wasn’t what I had told him, and it came out in group. He said I was dishonest, and [that] I should have told him that. I wasn’t thinking about that sort of question at the time, while I was doing my [offence] chain….He said that he was disappointed in me because I didn’t tell 15 him what I had told [Therapist], what I had put on the chain. I was a bit upset when he said that he was disappointed in me. I should have told him.” This placatory disclosure management style also influenced the consulting approach of this next man: “M comes through here the strongest of all the members; he’s the most outspoken. It’s like he’s the leader, and I felt that what he said meant - he meant what he said. I took more notice of what M said. He’s not like me, he’s very assertive, he’s very strong. He’s just this authority figure.” The goal of the men who exhibited a placatory style of disclosure management in these examples, as might be expected, surrounds winning the approval of others. While this might contribute to the cohesiveness of members of the treatment group, it would appear to add little to the individual’s engagement with broader, therapeutically significant matters. Those whose approach is characterised by an evasive disclosure management style are also inclined to consult. However, the quality of the engagement appears more robust than those who are more influenced by a placatory style, as illustrated here: “I mentioned it to him, just briefly, and we stood there and spoke of it, and in every detail of what I was talking about on Thursday. He asked me a simple question, that nobody else asked me, “and what happened previous to that?” Even I didn’t think of just playing and play-fighting, [I said] “but that has got nothing to do with it.” He said, “yes it has, because that meant, that gave you the knowledge that it would be safe to come into bed with you”. Well he went from a fuck-wit to somebody that showed about compassion. He patted me on the shoulder and just said, ‘hang in there mate’.” Some who had ruminated on an issue chose not to engage in consultation with others at all, and foreclosure on the process of engagement was evident at this stage: 16 “I don’t find it helpful to me in any way to talk about those things at all….” Also, merely passing on information to others, in the absence of an exchange considered to constitute feedback, was not considered to represent consultation in this context. Stage 5: Reflection Overall, five of the men underwent a reflective process. The term “reflection“ in this context is taken to mean the active and conscious consideration of issues in the light of external feedback: “Not much happened during the session, apart from I felt anger and sadness and a lot of pressure on myself. The impact came later, because when I was with the group I thought my chain was clear, by the time I finished it I was lost and I got more help on my chain after my group from the guys outside.” The reflection may concern the participant’s grasp of his offending: “Then I opened up to him and spoke to him. That was when it was possible, and that is when he put this question to me. It made me think of what happened previous to that at the time. That was never asked, I had been thinking that was relevant. I hadn’t been thinking that play-fighting was me grooming her.” The reflection may centre on a review of his self or his approach to his goals: “[I also thought about] some questions more about me and my background, that sort of thing.” “All this made me go easier on myself: OK someone is understanding, he has not judged me at all. I was judging myself more than they were. With the expectance [sic] of support, I went easier on myself, I felt a lot better about myself. It helps you to see things a lot clearer, so you can sort them out, get a better perspective on what the problem is.” 17 Alternatively, as a result of consultation, the client may hold to an original position. “It didn’t make me feel better in myself, or worse in myself; any way at all.” Such a conclusion represents the next exit point from the process of ongoing engagement. Stage 6: Re-evaluation and Re-engagement Having identified unresolved matters from the session, ruminated upon them, consulted with others, and followed up with a period of contemplative reflection, the client may then look to re-evaluate his situation. This reevaluation can be across any of three broad domains: his own perception of himself; his conception of his offence process; and action plans for the future. The re-evaluation may combine one or more of these domains. The following transcript excerpt illustrates all three of them. “It took a release - you weren’t being judge on yourself. There was acceptance, and so if they accept you, then you can accept yourself. / Once you got rid of all the bullshit instead of trying to hide it and all the rest of the shit that goes with it, then you can look at it a lot clearer, you can see the problem a lot clearer, / and hopefully you would do something about it.” Foreclosure at this stage is indicated by the participant’s satisfaction with his goal-attainment, therefore precluding the need to pursue identified issues further. For example, the man may have met core interpersonal goals merely by securing or retaining the emotional support of others: “I thought about it, after he mentioned it. It was just the question. He would ask me a question and I would give him an answer….The good thing is, it’s good to get it out of the system. It has been there for a long time, you have to tell somebody, otherwise it would come back to haunt you.” 18 In this example, the needs of the man to simply appease his questioner and to unburden himself appear to have been satisfied. We might presume then that while he may continue to engage interpersonally in this way his intention is achieved, and engagement in a therapeutically significant sense is, at this point at least, not indicated. The re-evaluation and re-engagement stage, while inferred from the statements, remains a theoretical one. It is untested, as the proceeding group treatment session was not included in the current study. For those participants who passed through the previous stages, without exiting at any point, it is presumed they are optimally motivated to participate in the next stage of the formal group therapy process. That is, these participants are, theoretically at least, sufficiently prepared to present a modified account of their offending, with the expectation of deepening their understanding and enhancing their confidence in the steps they can take to promote adaptive change. Discussion It became evident from the data that participants’ “out-of-group” experiences represented an important component of their engagement in therapy. During the first phase of the study it was found that most participants experienced aspects of the formal group therapy environment in ways that were constraining or otherwise limiting to their capacity to benefit from it. Once free of these elements during the out-of-session time, most sought to avail themselves of the type of information that they perceived was unavailable to them during the session. For many, such information was sought to minimise the distress they experienced, having been exposed to such potentially damning revelations. Social reality testing (through “consultation”) was an important mechanism for many in this quest. For a large proportion of men then, information was pursued in respect of their social evaluation in the light of their personal disclosures, as they sought to determine and limit the “damage” to their selves or their relationships. Typically, participants concluded from their consultation with others that the vilification that they had anticipated was not realised. Or, that 19 liberated from the need to put such a high proportion of their attentional resources into self-monitoring, they allowed these resources to be redirected into the blossoming of curiosity about themselves and relatively unimpeded inquiry into the latent processes involved in their offending. At this point, the blinkers created by their fears could be removed and they could consider and reflect upon alternative perspectives that subsequently became available to them. The way in which they went about this, and the degree and extent of ongoing engagement, was integrated into the descriptive model presented in this paper. The pattern revealed was found to predominantly reflect the disclosure management styles, which emerged from the first phase of the research. For those who exhibited an exploratory style, full advantage is taken of the possibilities for reprocessing opportunities to consider and reflect upon their experiences in therapy, as described by the model. By contrast, participants who relied primarily on an oppositional approach exited early from this process. Those who traversed the formal session employing an evasive approach were likely to gain new insights, following a process of reality testing involving other men with whom they had chosen to consult. Such insight may derive from often radical challenges to beliefs and attitudes, apparently jolting their preconceptions and availing them of new ones on which to reflect. Those who were most likely to be characterised by a placatory style of disclosure were observed to exit the process of ongoing engagement once interpersonal support was seen to be reconfirmed by them, or that damagelimitation has been carried out as best they could manage. In short, the difficult and painful business of relating to the matters raised by the disclosure encounter are often eased during out-of-group reprocessing. Depending on the approach of the client, this may be the result of the intellectual and emotional distance from the intensive nature of the experience in group, or by means of reassurance or exposure to previously unconsidered perspectives. Whether these experiences and encounters result in progress toward therapeutic engagement may depend on the qualities of the various facets of the out-of-group environment. 20 The study has a number of limitations, some inherent in the particularity of the context, and some inherent in the nature of qualitative research per se. The research was carried out in one prison-based location with a relatively small number of participants. Offenders who are represented, therefore, comprise only a narrow cross-section of the offender population. Applicability of the findings to offenders outside of this particular prison environment remains unexplored. In addition, the Out-of-Group Engagement model relies on the integrity of the data categories from which they were derived. The categories depend, in turn, on the fidelity of the coding and assignment of the units of meaning extracted from the raw data. Extensive use of quotations has been made in the paper to illustrate the connections between raw data and the conclusions drawn. However, the absence of independent reliability checking requires that the model remain tentative and of provisional applicability to other settings. Nevertheless, the findings provide interesting possibilities regarding the potential for out-of-session time to positively influence the development of therapeutic engagement and change. For the client, greater use of “inbetween” time enhances the potential advantages of creating a “therapeutic community” (Inciardi, 1996; Lipton, 1998). Greater responsibility for therapeutic change is devolved to the programme participants, the custodial staff becoming more the facilitators of group process. Actively involved in the process of change, it is likely that the men also become more engaged and less oppositional. As a consequence of the purposeful use of out-of-group time, the men have a greater expectation that processes are open to others, providing a positive model, or “social template” for them with regard to their interactions with others. The findings also raise issues for the professionals working within the offender treatment services. The significance of a warm and trusting client/therapist relationship has been established as one of the essential preconditions to behaviour change (Birgden, Owen & Raymond, 2003). Using the strength of the therapeutic relationship to model openness and responsivity to others is more likely to reinforce positive modes of interaction during out-of group time. By creating a climate of reciprocity and mutual 21 learning, and exploring ways in which the client can both experience and understand the processes of reflexivity and reflection, the potential to build insight and skill acquisition is enhanced. The harnessing of out-of-group time and the greater involvement of men in the process challenges workers to be less directive, allowing the process of change to occur within the client system itself. The process requires that the clinicians work at the client’s pace, with less emphasis on professional process in favour of more client-driven work. In this sense, the work becomes less didactic and more naturalistic and evolving. Facilitating opportunities for the men to process time on their own has the potential to maximise opportunities for both individual and group reflection. Exploring further opportunities for the men to experience a greater range of input from others may also be indicated: for example, facilitating group processes with graduates from the programme. Finally, the findings raise a number of institutional issues. Harnessing the usefulness of out-of-group time increases the potential for the service to be more responsive to the needs of the offenders in treatment. It requires active management – custodial staff actively involved in engaging the men in treatment. Within this context the custodial staff become increasingly important as they facilitate the congregation of the men and the facilitation of interactive peer processes. The role of custodial staff extends from the provision of humane, secure and safe containment, to actively promoting the change process. Necessarily with this change in emphasis, there are likely to be training implications. However, building an environment that utilises the resources of the whole of the service community would seem to have much to recommend it. 22 References Birgden, A., Owen, K. & Raymond, B. (2003) ‘Enhancing relapse prevention through the effective management of sex offenders in the community’ in Sexual Deviance: Issues and controversies (T. Ward, D.R. Laws & S.M. Hudson Eds.) Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Davison, D. C., Robins, C., & Johnson, M. K. (1983). Articulated Thoughts During Simulated Situations: A Paradigm for Studying Cognition in Emotion and Behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7(1), 17-40. Elliot, R. (1989) Comprehensive Process Analysis. New York: State University of New York Press Frost, A. (in press). Therapeutic Engagement Styles of Child Sexual Offenders in a Group Treatment Program: A Grounded Theory Study Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment Greenberg, L.S. & Pinsoff, W.M. (1986) The Psychotherapeutic Process New York: Guilford Press. Henry, J. (1999) ‘Changing conscious experience – Comparing clinical approaches, practice and outcomes’ British Journal of Psychology 90, 587-609/ Hubble, M.A., Duncan, B.L., & Miller, S.D. (Eds.) (1999) The Heart and Soul of Change: What works in therapy Washington DC: American Psychological Association Inciardi, J.A. (1996) ‘The therapeutic community: An effective model for corrections-based drug abuse treatment’ in Drug Treatment Behind Bars: Prison-based strategies for change (K.E. Early ed) Westport: Praeger. 23 Kanfer, F.H. & Schefft, B.M. (1988) Guiding the process of therapeutic change Champaign: Research Press. Lipton, D.S. (1998) ‘Therapeutic community treatment programming in Corrections’ Psychology, Crime and Law 4, 213-263. Rennie, D.L. (1992) ‘Qualitative analysis of the client’s experience of psychotherapy: The unfolding of reflexivity’ in Psychotherapy Process Research: Paradigmatic and narrative approaches (D.L. Rennie & S.G.Toukmanian Eds.) Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Rennie, D.L. & Toukmanian, S.G. (Eds.) (1992) Psychotherapy Process Research: Paradigmatic and narrative approaches Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Rice, L.N. & Greenberg, L.S. (1984) ‘The new research paradigm’ in Patterns of Change: Intensive analysis of psychotherapy process (L.N. Rice & Leslie S. Greenberg Eds.) New York: Guilford Press. Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques Newbury Park: Sage. 24 Author Note Author to whom correspondence should be sent: Dr Andrew Frost, Kia Marama Special Treatment Unit, Psychological Service, Department of Corrections, P.O. Box 45, Rolleston, New Zealand. Phone: +64 – 3 – 347 7867, Fax: +64 – 3 – 347 7861; Email: andrew.frost@corrections.govt.nz 25 Figure Caption Figure 1. Out-of-Group Engagement Model, identifying potential pathways toward and away from therapeutic engagement 26 Therapy Session Potential for engagement Potential for disengagement Successful recall of material AND Nothing significant recalled BUT Salient issues identified AND BUT Ruminates on identified issues AND BUT Consults No outstanding issue identified Issue not ruminated upon AND Reflects BUT Does not consult AND No reflexive response Re-engages Figure 1: 27