12599061_final res paper.doc (106Kb)

advertisement

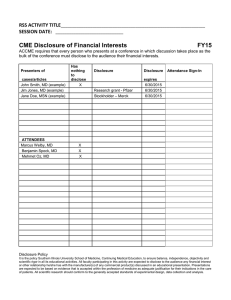

Therapeutic Engagement RUNNING HEAD: Therapeutic Engagement of Sexual Offenders Therapeutic Engagement Styles of Child Sexual Offenders in a Group Treatment Program: A Grounded Theory Study Andrew Frost1 1Kia Marama Special Treatment Unit PO Box 45 Rolleston Canterbury New Zealand Voice Email +64 3 347 7867 andrew.frost@corrections.govt.nz 1 Therapeutic Engagement 2 Abstract It is widely observed that child sexual offenders typically exhibit considerable reluctance to self-disclose at a level that reflects the full reality of their offending. Their successful engagement in relapse prevention-based programs is therefore problematic. This paper describes a study involving men undertaking a prototypical group treatment program, facing the challenge of revealing to others the details of their offense process. A procedure was developed to access their covert responses at the time of this encounter. From a grounded theory analysis, participants were found to employ various strategies to manage situations where self-disclosure was required. Four distinct disclosure management styles emerged: exploratory, oppositional, evasive and placatory; the latter three of which appear unfavorable to effective engagement in treatment. As well as suggesting ways of influencing disclosure management style, analysis indicated that it might be possible to predict these different orientations during routine assessment. Key words: therapeutic engagement; self-disclosure; child sexual offenders; disclosure management style. Therapeutic Engagement 3 Relapse prevention-based treatment has, over the last two decades, become the preferred approach to working with sexual offenders (Laws, 1998; Marshall, Fernandez, Hudson, & Ward, 1998). This is especially so in the treatment of those whose victims are children (Marshall & Anderson, 2000). The relapse prevention model as applied to sexual offending was originally adapted from the addictions field as a treatment maintenance strategy (Pithers, Marques, Gibat & Marlatt, 1983). It has since been developed as a more flexible and durable treatment conceptualization that better reflects the self-management focus of cognitive behavioral therapy. In its most recent manifestations the model incorporates recent work on self-regulation and related constructs (Ward & Hudson, 2000) and has been seen to reliably respond to a range of treatment needs (Bickley & Beech, 2002). Treatment programs commonly involve a group therapy format and require that each participant engages in detailed self disclosure about the processes involved in his sexually abusive conduct (Barker & Morgan, 1993; Marshall, 1999). This is typically the prelude to a rigorous process involving the examination and refinement of each client’s understanding and “ownership” of his offending as a patterned and predictable process. However, it is clear both from practice experience and from the literature (Scheela, 1992; Scheela & Stern, 1994) that the process of self-disclosure for these clients tends to be experienced as particularly aversive. It follows, and is also well documented (Garland & Dougher, 1991; Salter, 1988; Tierney & McCabe, 2002), that such demand typically gives rise to considerable resistance. Although some impress as motivated to reveal important sensitive information (such as undetected offending) from an early stage in treatment, others present as reluctant even to acknowledge their active role in the abuse for which they are convicted. A willingness to openly confront factors that motivated and maintained offending is generally seen as a key step to making the changes necessary to addressing re-offending risk. Such openness is therefore a primary requirement of treatment programs (Kear-Colwell & Pollock, 1997; Marshall & Anderson, 2000; Marshall et al., 1998; Salter, 1988), and considerable effort is invested in facilitating the shift from reluctance to compliance. This is the task of therapeutic engagement. The process of engagement in sex offender treatment, however, is not well understood. Marshall and others (Fernandez & Marshall, 2000; Marshall, et al., 2003) Therapeutic Engagement 4 have drawn attention to the low emphasis on context and process issues in the relevant literature. Extrapolating from the more general literature, they conclude that therapist qualities, client perception of those qualities, and therapeutic alliance are the key variables that predict positive treatment outcome. However, they acknowledge there is little known about the qualities of group treatment specifically applied to work with sex offenders. A rare study focusing on the “climate” of sex offender therapy groups (Beech & Fordham, 1997) suggests that therapists generating a strong sense of cohesiveness within groups were most successful. In short, conducive relationships, and especially client perception of such relationships, in confronting the personally daunting issues raised in sex offender therapy are likely to be important in successfully engaging clients. The study described in this paper represents an investigation of the experiences of clients faced with the prospect of self-disclosure. Self-disclosure was viewed as a critical aspect of the demonstrated willingness of men to participate functionally in an intervention to promote behavioral change, and therefore as a key marker of engagement. The aim of the research then was to shed light on how participants go about addressing the dilemmas posed by the disclosure encounter at the time of the encounter itself. Of particular interest were those qualities and processes present in that context and at that time that influence clients in confronting this task. Given that the present investigation sought to build theory rather than test it, a grounded theory method (Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990) was employed. This method has enjoyed support as a vehicle for this type of social science research goal (Gilgun, 1992; Henwood & Pidgeon, 1992; Rennie, Phillips, & Quartaro, 1988; Riessman, 1994). Typically, studies carried out according to a grounded theory regime generate a considerable quantity of raw data gathered from a relatively small number of research participants. Using this method, data analysis proceeds alongside collection. The two procedures cross-pollinate, contributing to an emergent explanation, which may eventually contribute to broader theory. Analysis begins with an initial set of raw data, which are divided according to units of meaning and subsequently grouped into categories. These categories are named according to the semantic content of each, and relationships are sought between the labeled categories. At the same time, the categories are regularly checked Therapeutic Engagement 5 against the data to ensure a “grounded” match. Gaps in the emerging information also provide a guide to decisions for subsequent data collection. The primary purpose of the current paper is to present this research, along with a brief overview of some of the outcomes. The methodology developed to carry out the investigation is described, and a significant outcome of the research, the discovery of distinct disclosure management styles, is presented in the form of a descriptive model. The significance of this model is proposed in relation to issues of treatment process and context, and especially the process of engagement. Finally, implications, limitations and proposals for further research are discussed. Method Context of the Research The site for conducting the research was the Kia Marama program (Hudson, Wales & Ward, 1998), based at Rolleston Prison, Aotearoa New Zealand. This is a prototypical and successful prison-based program employing a relapse preventionbased model in the context of an interpersonal group therapy modality. The point of investigation was the “Understanding your Offending” (or “Offense Chain”) program module. The particular focus for the study was offense pattern disclosure, and the attendant processes of group feedback and refinement. It was considered that this module provides the opportunity to access some of the richest and most concentrated sources of information about the man’s response to the invitation to engage in treatment. The direct research objective then was to identify personal and interpersonal factors that impact on therapeutic engagement in this instance, and to explore the group processes that contribute to those factors. The intended process of the study was to identify such events experienced by research participants as salient, as they occur in the context of group treatment. These events, along with observations and the subjective experience surrounding them, were then to become the subject of ongoing analysis. In order to access the experience of participants as directly as possible, a method of gathering the data from the articulated thoughts (Davison, Robins & Therapeutic Engagement 6 Johnson, 1983) of participants was devised, and these data were developed using a grounded theory analysis. Research Participants Participants were incarcerated offenders convicted of one or more sexual crimes against persons under the age of 16. Prior to their inclusion in this study, each had volunteered for inclusion in the Kia Marama program, which is based in a standalone prison unit. Over the course of the study, treatment groups were commencing every one to two months. Inmates accepted for treatment were transferred to Rolleston from regional prisons. Of the 16 primary participants, their ages ranged from 23 to 65 with a mean age of 40.2 (SD = 12.7). The convictions of this group involved indecent assault, unlawful sexual connection and sexual violation. Two were Maori and 14 were of Pakeha (non-Maori, generally European) ethnicity. Length of sentence ranged from 24 to 72 months, with the mean being 40.3 (SD = 14.8). Number of victims ranged between one and eight, with a mean of 2.75 (SD = 2.2). None of the primary participant group had a current psychiatric illness, although five had psychiatric histories. Procedure Treatment intake groups targeted for inclusion in this research were approached and invited to take part in the study. Participation essentially involved being videotaped during a group therapy session, followed by an interview with respect to personal experiences of that session. Because other members of each participant’s treatment group would figure in this process (by providing the context in which interviews with primary participants would take place) their consent was also necessary. Where such dual consent was gained, each primary participant was videotaped in the context of a group therapy session that was dedicated to eliciting details of the offense chain for that participant. Following the group therapy session, the participant was asked to carry out a series of tasks. The central aspect of these tasks was to nominate and record features of three events from that session that he considered to be the most personally salient. These salient events were defined in terms of discrete episodes, those that maximally engaged the participant’s attention at the time the event occurred, according to his Therapeutic Engagement 7 own appraisal. These events and certain contextual information were recorded (written) by the participant on a form designed for this purpose. Each participant was also asked to record (voice) onto a dictaphone a general account of the events of the session immediately following it. It was intended that this data would function as a check on the validity of his appraisal, on the assumption that for an event to be accepted in the data as genuinely salient it could be expected to figure in the participant’s general account. Before the next group therapy session the participant joined the researcher in the room where the session had taken place. Here, he was asked to view the video recording and to identify the three episodes he had nominated. Once located on the videotape by the participant, the identified material was indexed according to the counter on the tape recorder so that it could be readily located. For this exercise, the participant was encouraged to imagine himself as vividly as possible as though he were re-experiencing the session itself. Efforts were made by the researcher to elaborate the experience by verbally eliciting from the participant the detail of his emotional responses associated with the session, along with his recall of sensory information. In this way the goal was to recreate the “tone” of the earlier encounter in therapy so that the participant was best primed to respond as if he were again in that situation. The salient episodes from therapy selected by the participant were then replayed on the TV monitor as sections of video in the presence of both participant and researcher. Each of the episodes was started and stopped (freeze-framed) at frequent intervals in order for the man to articulate his subjective experiences (to “think aloud”) throughout that part of the encounter. He was also encouraged to elaborate thoroughly on these experiences throughout the episode. An interview guide was developed to assist in this process based on a number of prompts: General What are you noticing there/what’s going on? What are you thinking here/what’s on your mind at this point? How did that leave you feeling? Therapeutic Engagement 8 What did that mean to you? Elaboration Tell me more about that/what else? What is that leading you to think about there? How did you see that/what did you make of it? What is significant about that to you? What did you want to do/what was your intention? The participant was encouraged to refer to salient moments occurring in the recorded material as they became apparent during the tape play back. The researcher also intervened to elicit the articulation and elaboration of experiences. This interview was audio-recorded, transcribed, and considered alongside other data for grounded theory analysis. Analysis. A grounded theory approach was the main organizing principle for analysis. The wealth of data from the diverse sources were integrated, matched, and combined into analyzable categories in the procedure explained. Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) monograph was used as the first point of reference for the procedure. Interview transcripts were collected, one batch at a time, as successive treatment groups passed through the relevant stage in the program. On each occasion that this occurred the transcripts were placed alongside other sources of data and “fractured” (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) into meaning units (or “chunks” of meaning). Initially, these chunks were derived from a line-by-line analysis (Charmaz, 1995), being divided according to the smallest possible sequence of text that still retained individual meaning as illustrated: I suppose that is what his job is, to try and see if he can change your mind, or have another thought about it. / Perhaps seeking me to become uneasy about the situation, / that I might say something I might not have said something previously, / or to try to get me angry; / I’m not quite sure. / He is trying to make you feel uncomfortable; / he is trying to get you to say something, that possibly might not have intended to say. / Therapeutic Engagement 9 Each unit was initially labeled with a note relating to its semantic quality and the units were then grouped together according to their labels. As this proceeded, the groups were condensed into clusters at a higher level of abstraction to capture and combine categories of similar meaning. That is, sub-categories were combined with similar sub-categories into broader categories. The process of collating categories was followed by preliminary attempts to identify potential relationships between them, employing “concept mapping” techniques (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). Data continued to be assigned to categories as each data source was analyzed. The gradual nature of the data collection facilitated a process of analysis involving the alternate compressing and expanding of the data in a semantic sense. This process is explained. As the data were accumulated, hypothesized relationships between categories were postulated (compression), then the categories were “trialed” by re-opening the categories (expansion) in order to test the hypotheses for goodness of fit with the data themselves. The relationships validated from this process directed subsequent data collection, by for example guiding more direct and specific questioning along the lines of the themes that had emerged. Employing Strauss & Corbin’s (1990) axial coding paradigm, which defines the elements of a causal sequence and applies them to the categories of data, these procedures gradually revealed a narrative. The narrative described how participants in the study navigated a pathway through the disclosure session according to their expectations and experience of it. The elements of this narrative are made explicit in the results section. As analysis by these means progressed, the central principle to this “navigation” process was established. Participants, it was revealed from analysis, decided how to manage the session by what one man referred to as “getting it right”: a combination of the participant’s goals for the session and the strategies for achieving those goals. This principle was tested and confirmed using the procedures described above as a central category to which all others related, and which was axiomatic to the emerging account of how engagement occurred. This super-category is referred to in the grounded theory literature as the “core” category. Once this was revealed, the process could be described in terms of a flowing, sequential account of what was Therapeutic Engagement 10 going on when participants confronted the disclosure encounter. Each of the primary participants’ narrative accounts could then be identified. Eventually, following this method, no new categories around the disclosure management sequence were being formed and no further refinement was occurring. That is, all newly culled units of meaning were codable into existing categories. Strauss & Corbin (1990) refer to this stage of the categorization as “saturation”. The resulting narrative accounts were found to fall into four broad categories, resulting in four disclosure management styles. A model describing these styles is outlined in the next section, following a brief account of the process and findings from which the model emerged. Results Analytic Process Initial stages of the data analysis revealed a number of common themes as the men faced the disclosure process. These were the “raw”, preliminary categories that directed ongoing collection and analysis. One of these, labeled experience of psychological overload, is illustrated with examples from meaning units: “It seems like you are getting questions from every direction, but there isn’t really that many people speaking.” “ It’s a bit like an interrogation; it’s like being overloaded.” “So between J and the therapist I was getting beaten: like a bat and ball - like punch drunk” “I didn’t realize that W had gone on - I heard, but I didn’t take it in.” The analysis at this point was in its early stages. The research task was to develop a refined understanding of these initial themes, to make sense of their influence, and to discover dynamics operating in this situation that would account for their incidence and their course. For example, the category labeled experience of psychological overload was combined with other rudimentary categories and became subsumed under the label reactions to impact. Therapeutic Engagement 11 Once all the transcripts were categorized, relationships were established between the categories. As relationships were observed to occur, some categories were re-labeled, or were telescoped together, and some new categories were identified. At this intermediate stage, a dynamic process was revealed by which participants were seen to confront the various risks and opportunities they perceived in the disclosure encounter. Essentially, orientation to the task of disclosure appeared to be founded on certain predispositional factors (a category) comprising motivational, assumptive and perceptual elements (sub-categories) brought to the encounter by participants. Subsequently, participants were observed to adopt particular goals and strategies with respect to the risks and opportunities they perceived. These goals and strategies manifested in a set of distinctive response styles. Response styles were, in turn, seen to be characterized by particular markers of progress, sources of impact and reactions to impact, reported by participants as they experienced events salient to them during the session. Disclosure Orientation An outcome of progressive grounded theory analysis was that the common imperative among participants (to “get it right”) was established as the core category and found to be identified with a range of goals. These goals were observed to be combined with a range of strategies for achieving them. The combinations and permutations of these goals and strategies form the basis for understanding the construct of disclosure orientation. The disclosure encounter can be seen to represent a range of challenges to participants. The particular nature of the challenge depends on the immediate concerns and priorities of the individual, thereby establishing his approach to the task. The range of approaches came to be defined in the study as dimensions of disclosure orientation. The disclosure orientation concept itself denotes intention and can be viewed as the dominant stance adopted by the man, characterizing his approach to the encounter. Figure 1 presents the research outcomes in a conceptualized form, representing the disclosure orientation model and incorporating the four disclosure management styles, one associated with each orientation. The two axes of goal and strategy, generate four broad disclosure orientations, which are depicted as discreet elements. It Therapeutic Engagement 12 follows that the disclosure orientation associated with any individual can be plotted on this graph. ----------------------------------Please figure 1 about here ------------------------------------ According to this model, disclosure goal relates to matters of personal validation, and particularly, to the principle source of such validation. That is to say, these goals are influenced principally by whether the individual puts greater emphasis on the evaluation of others or, alternatively, on his own evaluation to this end. Where he looks principally to others for such validation he is said to be other-directed; where the man emphasizes a self-validating approach he is seen as self-directed. The self / other continuum intersects with the second dimension of Figure 1: that of the disclosure strategy continuum. This latter notion describes the full set of active responses of participants to managing the challenges that the session represents to them. The two extremities on the strategy continuum are labeled as open and closed. In the course of the disclosure encounter, opportunities are created for sharing ideas, hypotheses, suggestions, enquiries, advice and explanations. Whereas some clients favor relative openness to such exchange of information during the session, others are seen to adopt a more circumspect or closed approach. Disclosure Management Style According to the model, the combination of predispositional factors, as exhibited by any one client, is closely associated with disclosure orientation. However, as well as denoting intention, disclosure orientation also influences means: how the client goes about managing the encounter. In this way, predispositional factors have a direct bearing on the way in which, in a behavioral sense, he navigates a course through the encounter. There emerge then four discrete disclosure management styles, arising directly from the four permutations of goals and strategy pairings. The constraints operating on the course of their disclosure again reflect the intensity of this experience for the men involved, as they seek to balance their need to provide an explanation for their behavior and themselves (whether this is driven by an “internal” Therapeutic Engagement 13 need to make sense of their offending or an “external” one to be acceptable to others) with the perceived demands of the immediate environment. Irrespective of the particular goals and strategies involved then, their predicament engenders a compelling sense of the need to “get it right.” Depending on the particular disclosure orientation, getting it right can involve a range of approaches from finessing one’s way through the encounter with a minimal level of exposure to harmful selfrevelation, through to grasping the nettle of disclosure and therefore maximizing opportunities to elicit helpful feedback from other participants in the encounter. Providing “correct” responses in the “right” way therefore is a common concern of the men in this situation, whether their purpose is to oppose, evade, placate or explore. A brief profile of each of these disclosure management styles, along with a summary of relevant characteristics derived from data in the study is described in the next section. The Four Disclosure Management Styles Exploratory style (self-directed / open strategy) After W [group member] had said, “I’m lost”, I said, “good!” At that particular stage, I turned introspective…. I said “good” …because I could see an opportunity to enlarge on what I had just done. On this occasion, it is someone who is lost; the group can get together now with me, with W to fill in the gaps, get something to work on. The people can put a little piece of information here and there to fill in the gaps. W’s lost, I’m lost; but others can have a brainstorm. The exploratory disclosure style is characterized by both a relative openness around disclosure and an inclination to interpret information in ways that are consistent with self-discovery. Those who are inclined toward this approach tend to encourage exchange and the free flow of information in the session. As they seek to make sense of their situation, such individuals look to integrate information from external sources with existing understandings, and even a Therapeutic Engagement 14 preparedness to replace such understandings, in a search for greater clarity or accuracy. They seek to manage the encounter with a spirit of enquiry, and a reflective and considered attitude to feedback. Emerging issues are met with a curiosity-driven stance, as they endeavor to build on or to modify pre-existing understandings. Although they are primarily concerned with discovery, these participants are nevertheless at times wary of the potential for painful experience such as rejection by others. But while they may feel some ambivalence toward revealing themselves, they tend to welcome the prospect of unburdening, and savor a sense of cathartic release in doing so. Those events representing opportunities to integrate new information are generally the most salient for these participants. Such events are associated with a positive sense of stimulation and appear to enhance engagement in this case. Oppositional style (self-directed / closed strategy) I felt that he’s not believing me; this is not me ….He was trying to make it the truth, something that it wasn’t. He was twisting it all around, changing the outcome of it…. I think it was a lot of bullshit - constructing something that’s not there. This disclosure management style contrasts markedly with the previous one in that it is associated with an orientation characterized by an intention to pursue a policy of resistance to re-interpretative or confrontative input generated in the disclosure forum. In common with the exploratory style, however, self-directed validation is still to the fore. Those participants who come to the encounter emphasizing a self-directed approach combined with a closed disclosure strategy exhibit a concern with promoting the status quo. Generally, they habitually and explicitly oppose feedback that is contradictory of their opening position, typically viewing it as personal attack. By adopting this oppositional style of managing the situation, they seek to prevent the admittance of alternative constructions of their account, and may actively counter such challenges. In this way, their experience of the session comes to be dominated by a Therapeutic Engagement 15 sense of being under siege, which they are inclined respond to by further entrenching their position. From the playing out of such interaction, these men are likely to emerge with their understanding of themselves and their behavior minimally changed. Evasive style (other-directed / closed strategy) All those years of fighting to put it behind me. It’s been in there somewhere, but I’ve trained myself all those years to cover it up, in case someone found out - being exposed, made public. I’ve hidden these things for all these years. Even from myself…. But my mind is going over and over about [year of original offending]. I’m [age] now, a lot of my life has happened since then, and I have hidden this away for so long. When I got out of borstal and came back home it wasn’t discussed.... Here it [the offense] is being exposed for everybody; stuff even I’ve hidden from myself. It is bloody terrifying. The core features of those who predominantly display this orientation are their fear of negative evaluation, and their inclination to adopt a strategy of concealment or deception. Research participants adopting this mode tended to cite a concern with social exposure and subsequent emotional harm as the justification for this response to the encounter. A key predispositional feature is ambivalence. The men who adopt this orientation appear both drawn to the benefits of disclosure and repelled by the fear of experiencing distress. In essence, there prevails a pervasive sense of personal fragility surrounding the continual threat of exposure. The therapy session is construed as an ordeal, and emotional survival is considered paramount. There are active and passive forms of response to this perceived plight. Some resort to a range of active subterfuges designed to manipulate the focus of the encounter as they seek to evade or avoid the disclosure of information associated with shame. In its passive form the evasive style is expressed in terms of suppressing Therapeutic Engagement 16 painful emotion, or attempting to supply the minimal response gauged to be acceptable. Clients whose approach to self-disclosure is characterized by an evasive style appear to be motivated by some desire to profit from the experience while attempting to avoid revealing key aspects of their personal history. Primarily they are avoidance driven. They enter the encounter having anticipated a range of personally damaging contingencies, and often having planned responses to these contingencies in a despairing attempt to avoid the expected harm. On being confronted with the objects of their fears in the course of the encounter, these participants typically experience an urge to physically escape it. Placatory style (other-directed / open strategy) It was accepted by [Therapist]; he would have said if he hadn’t accepted it. [Therapist] turns back to the board there, and I’ve got a sense of relief for me that he has gone to the board to address the board and put whatever I had answered him on the board. And think about it - of how he had put it on the board for the group to see. A relief that I’ve come out with the right answer. [Had I got it wrong,] I would have felt put down because my thinking was wrong. I led [Therapist] to believe that - I led him to believe that I was just thinking it was all right to do that what I did. I was quite relieved that I got away with that answer, and explained to the group that I have changed over the last ten years. Those participants who, during the disclosure encounter, emphasize a placatory management style exhibit a primary concern with maximizing opportunities to secure the support of others. This priority promotes the attraction for these participants of presenting in a favorable or sympathetic light. To this end, their participation often conveys what are ostensibly commendable levels of self-disclosure. They are sensitively aware of the presence of others and conscious of the fact that they are continuously generating a socially evaluated impression. The need to manage this Therapeutic Engagement 17 impression is an immediate concern and tends to over-ride more self-directed priorities. There exist similarities between this disclosure management style and the evasive style. For instance, while in fact both approaches are concerned with the goal of satisfying the expectations of others, participants of either orientation may, in certain circumstances attempt to convey an impression of being self-directed. However, the distinguishing feature of action associated with the placatory style is the concern with securing emotional support. The goal here is approach-motivated: to have oneself acknowledged, heard, affirmed; in short, to be acceptable to others. In contrast to the strategy associated with the evasive style (which emphasizes avoidant, reactive attempts to stymie information), here there is a proactive focus on creating a favorable impression. The emphasis is on aligning oneself with others rather than insulation from emotional harm. Of course, to publicly accept the identity of a child molester is likely to be viewed as inviting threat to positive evaluation. However, social survival tends to be valued above the intra-personal risks associated with personal disclosure, and there is a danger that these men may accede to inaccurate accounts of themselves or their behavior purely for the purpose of avoiding interpersonal rejection in the immediate context. Personalities and relatedness are the important catalysts to therapeutic engagement here, as favorable conditions are created when the experience of social approval is paired with therapeutically relevant disclosure. Discussion The present study set out to explore issues surrounding the therapeutic engagement of incarcerated child sex offenders in a group-based relapse prevention program. Specifically, the research examined how participants responded to the definitive challenge of comprehensive self-disclosure. The question was addressed from the point of view of participants themselves. It is suggested here that the disclosure management model generated from the study is a useful heuristic in approaching the engagement issue. Therapeutic Engagement 18 A key indicator of the functional engagement of child sex offenders in a relapse prevention-based group treatment program, it is argued here, is the accurate and comprehensive disclosure of certain personal information. Such information is required to be of a type, and presented in a way, that facilitates open exchange in the group, pertinent to enhancing the discloser’s understanding of his offense process, and conveying his sole responsibility for his offending. The model depicts four distinct orientations to disclosure, and each is associated with a particular coping response, or management style. The first disclosure management style grouping is represented by those participants whose approach is characterized by an apparent inclination to confront abusive behavior relatively directly. In contrast to the denial, evasion or unreflective compliance characteristic of the others, this group exhibited an exploratory posture toward the factors that had motivated and maintained offending . The three remaining disclosure management styles might be described as essentially “resistant” in nature. One of these is an overtly oppositional style. While associated with denial and minimization, and commonly predicted in the literature as the standard approach of these clients, this style may represent the dominant approach for only a proportion of those men in treatment who actively avoid open and direct self-disclosure. The two other “resistant” styles of disclosure management (placatory and evasive) emerged as more covert, and perhaps less readily identifiable, means of avoiding engagement. These latter approaches suggest a more ambivalent attitude toward committing to change. Limitations of the Research The study was conducted in a single prison-based location with a relatively small number of research participants. We must assume that offenders who are represented (that is, those who are detected, convicted, incarcerated and volunteer for treatment) comprise only a narrow cross-section of the child sex abuser population. Applicability of the findings to those falling outside of this category is, as yet, untested. The model remains tentative and of provisional applicability to other settings. Therapeutic Engagement 19 Since the completion of this initial study, further data have been collected at the site of the original study, involving a further six research participants. Analysis is currently underway, providing an opportunity to test the model and to introduce such checks as inter-rater reliability. Some Implications of the Four Styles of Disclosure Management for Therapeutic Engagement Child sex offenders as a population have often been considered uniformly resistant toward responsible self-disclosure (Salter, 1988). The disclosure management model paints a more complex picture. It challenges the simplistic notion that “resistance” in child sex offenders is a monolithic phenomenon. A reluctance to reveal emotions, intentions and planning with respect to this type of offending is here presented as multi-faceted. The model also generates a picture of resistance that is not static but relational and dynamic. That is to say, the model provides a view that such practices as evasion and placation appear to be directly influenced by interpersonal responses to them. Identifying the approach to disclosure management in a client and an awareness of the associated feelings and beliefs may be important to understanding how to promote functional engagement. This view suggests the importance of developing sensitivity to how the individual perceives personal and interpersonal risks in this situation, as well as the ways in which he attempts to protect himself, or by other means to advance his goals. In this way, accurate early assessment of a client’s disclosure management style could make treatment more efficient and effective by neutralizing time-consuming and often fruitless confrontation. Hopefully, clients can learn alternative ways of promoting their interests by engaging in collaborative practices and thereby freeing up intervention resources to be expended on matters of relevant content. A General Clinical Approach The model also has implications for a more general clinical approach to providing an environment that is more conducive to disclosive practices among participants. Therapeutic Engagement 20 The promotion of an overall climate of interpersonal openness appears warranted. This should apply not only to those presenting sensitive information, but also to the responses of other group members to that disclosure. That is, transparency of social response to the discloser appears desirable, as well as feedback that encourages broader, more diverse considerations. These considerations might embrace evaluations of group members, concerning how they view the fact of the disclosures and what new light they may see the discloser in. Where such transparency is unavailable, clients appear motivated to invest energy and resources unproductively into monitoring such evaluations. In any case, where the group “climate” (Beech & Fordham, 1997) has been well developed one could be optimistic that such evaluations would be inclusionary of the discloser. Enhanced transparency may assist in neutralizing mistrust and avoidance, and may encourage self-disclosure in relevant domains. Open speculation on the values and intentions of the discloser toward his task would also seem to be helpful. It is not suggested that this be carried out in a personally evaluative way, but in a manner that provides the opening up of possibilities for clients to revise their actions in relation to their intentions. These could be offered to the client in terms of reflections and alternatives rather than pronouncements, so that the client is freed to match his intentions with broader goals and values. This proposed strategy may empower clients to identify their sense of agency and personal accountability. It provides a possible counter to any inclination toward passivity or apathy, and a way of promoting personal responsibility for riskmanagement. In order to establish a climate of mutual curiosity, it is suggested that a context of safety needs to be established and manifestly demonstrated. For clients to participate in open and direct disclosure, as well as to attend to challenging feedback, a forum for personal acceptance is indicated. This could be reflected in the general sub-culture of the milieu of the therapy facility as a whole, as should the notion of strengthening the treatment context as a community of concern around the issue of child sex offending. Suggestions for Further Research Therapeutic Engagement 21 Beyond replication of this study, a two-tier approach to extending the research around disclosure management style is suggested here. The first tier concerns the durability and stability of disclosure management style as the client progresses through treatment. We might expect to detect here a pattern of clinical response that relates to the identified disclosure style. The second tier relates to the investigation of relationships between this construct and other substantive areas in the field of sex offender treatment. Should the construct prove robust, some useful second-tier areas for investigation relate to its correspondence with other identified etiological variables, such as schema and interpersonal style. A promising stratum here is the investigation of the relationship between disclosure management and attachment theory (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Bartholomew, 1990). The development of theory around this latter construct in the field of sex offending has guided research, for example, into the attachment styles exhibited by different types of offender (for instance, Smallbone & Dadds, 1998), and is widely influential in the assessment and treatment of offenders in programs (Fisher & Beech, 1999; Marshall, 1999). Attachment styles, as strategies for conducting emotional relationships, are hypothesized by Ward, Hudson, Marshall, & Siegert (1995) to account for the various means by which adult relationships succeed or fail, and may be predictive of the kind of sexual offending perpetrated. On the face of it, there is a marked correspondence between attachment style and disclosure management style. For example, features of those characterized as exhibiting “preoccupied” and “fearful” attachment styles as originally described by Bartholomew (1990) are characteristically reflected in those participants in the current study who were observed respectively to display placatory and evasive disclosure features. The placatory disclosure management style for instance is characterized by otherdirectedness and capitulatory attempts to meet the expectations of others. These features are consistent with the expectations of someone whose sense of personal unworthiness in relation to others motivates focused approval seeking. Conclusions The early and accurate identification of disclosure management style in clinical settings may promote more efficient and effective use of therapy time. A more Therapeutic Engagement 22 general task for treatment providers is to establish the sort of clinical context that is most likely to attract clients to commit to open and direct self-disclosure. As therapists we must attune more sensitively to client phenomenology around disclosure. More specifically, we need to attend to the experiences and concerns of the discloser. Thus, we can respond more effectively to promote engagement. Therapeutic Engagement 23 References Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An Ethological Approach to Personality Development. American Psychologist, 46, 333-341. Barker, M., & Morgan, R. (1993). Sex Offenders: A Framework for the Evaluation of Community-Based Treatment. London: Home Office. Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of Intimacy: An Attachment Perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. Beech, A., & Fordham, A. S. (1997). Therapeutic Climate of Sexual Offender Treatment Programs. Sexual Abuse: A Journal; of Research and Treatment, 9, 219-223. Bickley, J. A., & Beech, A. R. (2002). An Investigation of the Ward and Hudson Pathways Model of the Sexual Offense Process With Child Abusers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(4), 371-393. Charmaz, K. (1995). Grounded Theory. In J.A. Smith, R. Harre, & L.V. Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking Methods in Psychology. London: Sage. Davison, D. C., Robins, C., & Johnson, M. K. (1983). Articulated Thoughts During Simulated Situations: A Paradigm for Studying Cognition in Emotion and Behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7(1), 17-40. Fernandez, Y. M., & Marshall, W. L. (2000). Contextual Issues in Relapse Prevention Treatment. In D. R. Laws, S. M. Hudson, & T. Ward (Eds.), Remaking Relapse Prevention with Sex Offenders: A Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Fisher, D., & Beech, A. R. (1999). Current Practice in Britain with Sexual Offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(3), 240-256. Garland, R. J., & Dougher, (1991). Motivational Interventions in The Treatment Of Sex Offenders. In W. R. Miller & M. S. Rollnick (Eds.), Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior (pp. 303-313) New York: Guildford Press. Gilgun, J. F. (1992). Hypothesis Generation in Social Work Research. Journal of Social Service Research, 15 (3/4), 113-135. Therapeutic Engagement 24 Glaser, B. (1978). Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. San Francisco: Sociology Press. Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine. Henwood, K. L., & Pidgeon, N. F. (1992). Qualitative Research and Psychological Theorising. British Journal of Psychology, 83, 97-111. Hudson, S. M., Wales, D. S., & Ward, T. (1998). Kia Marama: A Treatment Program for Child Molesters in New Zealand. In W. L. Marshall, Y. M. Fernandez, S. M. Hudson, & T. Ward (Eds.), Sourcebook of Treatment for Sexual Offenders (pp. 17-28). New York: Plenum. Kear-Colwell, J., & Pollock, P. (1997). Motivation or Confrontation: Which Approach to the Child Sex Offender? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24(1), 20 - 33. Laws, D. R. (1998). Relapse Prevention: the State of the Art. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(3), 285-302. Marshall, W. L. (1999). Current Status of North American Assessment and Treatment Programs for Sexual Offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(3), 221-239. Marshall, W. L., & Anderson, D. (2000). Do Relapse Prevention Components Enhance Treatment Effectiveness? In R. Laws, S. Hudson, & T. Ward (Eds.), Remaking Relapse Prevention with Sex Offenders: A Sourcebook . Newbury Park: Sage. Marshall, W. L., Fernandez, Y. M., Serran, G. A., Mulloy, R., Thornton, D., Mann, R.E., & Anderson, D. (2003). Process Variables in the Treatment of Sexual Offenders: A Review of the Relevant Literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 8, 205-234. Marshall, W. L., Fernandez, Y. M., Hudson, S. M., & Ward, T. (Eds.). (1998). Sourcebook of Treatment for Sexual Offenders. New York: Plenum. Maykut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide. London: Falmer Press. Pithers,W. D., Marques, J. K., Gibat, C. C. & Marlatt, G. A. (1983). Relapse Prevention with Sexual Aggressives: A Self-Control Model of Treatment and Therapeutic Engagement 25 Maintenance of Change. In J. G. Greer & I. R. Stuart (Eds.), The Sexual Aggressor: Current Perspectives on Treatment (pp. 214-234). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Rennie, D. L., Phillips, J. R., & Quartaro, G. K. (1988). Grounded Theory: A Promising Approach to Conceptualisation in Psychology? Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 29(2), 139-150. Riessman, C. K. (Ed.). (1994). Qualitative Studies in Social Work Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Salter, A. C. (1988). Treating Child Sex Offenders and Victims: a Practical Guide. Newbury Park: Sage. Scheela, R. A. (1992). The Remodelling Process: A Grounded Theory Study of Perceptions of Treatment Among Adult Male Incest Offenders. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 18(3/4), 167-189. Scheela, R. A., & Stern, P. N. (1994). Falling Apart: A Process Integral to the Remodelling of Male Incest Offenders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 8(2), 91-100. Smallbone, S. W., & Dadds, M. R. (1998). Childhood Attachment and Adult Attachment in Incarcerated Adult Male Sex Offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 13(5), 555-573. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage. Tierney, D. W. & McCabe, M. P. (2002) Motivation for Behavior Change Among Sex Offenders: A Review of the Literature. Clinical Psychological Review, 22, 113129. Ward, T. & Hudson, S. M. (2000). A Self-Regulation Model of Relapse Prevention. In D. R. Laws, S. M. Hudson, & T. Ward (Eds.), Remaking Relapse Prevention with Sex Offenders: A Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Ward, T., Hudson, S. M., & McCormack, J. (1995). Attachment Style, Intimacy Deficits, and Sexual Offending. In B. K. Schwartz & R. Cellini (Eds.), The Sex Offender: Corrections, Treatment and Legal Practice (Vol. 2, pp. 2.1-2.14). New Jersey: Civic Research Institute, Inc. Therapeutic Engagement 26 Figure 1: Disclosure Orientation and Disclosure Management Style Self-Directed Goals Opposition Exploratory Style Open Strategy Placatory Style Evasiv Other-Directed Goals