12653928_FINAL SCRIPT_Family History Society of NZ.docx (50.53Kb)

advertisement

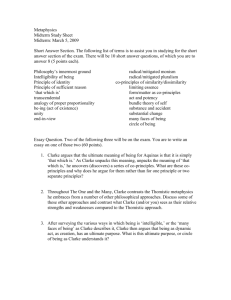

Presentation for the Family History Society of New Zealand, 2pm Sunday 1st September 2013 SLIDE 1: FROM HAUNTED HOUSE TO REGIONAL TREASURE Today’s talk is about the transformation of an ordinary family home into a significant Regional Object, listed on the New Zealand Historic Places Trust’s Register of heritage buildings. I’ll be telling the story from a public history perspective and uncover the process whereby a private family world – the land, house and contents – is converted into a museum collection. The land was first purchased in 1885, and Dr Alexander Clarke and his wife Mary, recent migrants from Scotland built the house, Glorat, in 1886. Glorat was held in the same family for 3 generations. Then in the 1970s the house was reinvented into an artefact in a Museum & Heritage Park setting in Maunu on the outskirts of Whangarei, Northland. Since its establishment, the Museum & Heritage Park operations have been partially funded by the Whangarei District Council via an Annual Operating Grant: door admissions and souvenir shop sales are other vital income sources. The house is locally known as The Clarke Homestead. Over time the homestead and property has been reconstructed into a social history story for school students and tourists. Local volunteers who were history enthusiasts and had the vision of a Heritage Park undertook most of the work. The Clarke Homestead in essence is a story about an ordinary family home. In his time Alexander Clarke was a doctor and because of his work, he was a public figure in the community. His home has none of the grandeur of Larnarch Castle or Olveston House in Dunedin. It is its ordinariness – the modest, working family home – combined with the fact that the current owners, museum and heritage enthusiasts, and what they have done to the home, that transforms Glorat into a local ‘icon’ of “white settler heritage”. Glorat is unique. In Australasia very few original family homes exist as museums in their original environment, in reasonable order and containing the paraphernalia and possessions of the same family. And taking into account the 1 local flora and geology – of rolling, volcanic countryside clad in native bush – lends the farm setting further uniqueness. The last inhabitant of the homestead was Basil Clarke, a bachelor. He loved music, sport and socialising. The family’s housekeeper, Myra Carter, also lived in the house. Myra is a shadowy figure in the archives even though she crosses over two generations of the Clarke family story. As Basil aged, the garden became increasingly overgrown and unkempt. The children from Maunu School, which is just across the road, called it ‘the haunted house’. Today’s talk is divided into 3 parts: the first is about the Clarke Family History Story, and starts in 1886. The second story focuses on when the Homestead was sold and formed the basis of a Museum & Heritage Park for the Whangarei District in 1973. The third story is about the challenges faced with maintaining and conserving this iconic heritage building. 2 SLIDE 2: “The Story” MIGRATION & SETTLEMENT Who were the Clarkes? And why did they come to New Zealand? These are the usual sorts of questions that family and public historians ask. Dr Clarke had siblings who had migrated to New Zealand and Australia in the 1860s. In the early 1870s Alexander Clarke visited his two brothers who had migrated to Pollock on the Manukau Harbour. He commented in correspondence that “his wife and bairns, like himself, would blossom under more primitive circumstances and surely fresh air and more liberty can be had at a cheaper rate.” Alexander and Mary Clarke left his successful medical practice behind in Scotland and migrated to New Zealand with their three sons in 1884. Neither a ‘first wave’ migrant or a ‘pioneering labourer’ Dr Clarke and his wife came to New Zealand for reasons like most Irish, Scottish and English immigrants of 1870s-1880s – to give their children better opportunities which meant better work opportunities, as well as better access to fresh air and the hunting sports that came with it. It was an egalitarian land based life the Clarkes sought and achieved. Over time the family continued to extend as they married into other local families in the Whangarei District. Most settled into farming. SLIDE 3: LAND SURVEY The land was first surveyed in 1879. In 1885 Dr Alexander Clarke bought 25 hectares for his family. Like a land bank, chunks of farm land were sold off as each of Dr Clarke’s three sons’ married. Later, most of Dr Clarke’s land comes back under the single ownership of the Whangarei Museum & Heritage Park Trust. 3 SLIDE 4: GEOGRAPHIC CONTEXT: MAUNU Where is Maunu? Maunu is prime real estate. It’s just out of the Whangarei city boundary. The 25-hectare property includes farmland and surrounding native bush. Down in the valley there’s a stream and swampy hollow where pukekos and weka graze. Glorat house has fantastic views of the Whangarei Harbour and the Whangarei Heads. Over time, from out of the native bush the grounds were slowly established, adapting rolling volcanic countryside into farmland and a domestic garden, including a tennis court. SLIDE 5: KEY POINTS IN THE FAMILY HISTORY Each generation has a story: In 1885, the year they moved to Whangarei, the Clarke’s joined the St Andrews Presbyterian Church. Dr Alexander Clarke had a pharmacy in Whangarei Township and ran his doctors surgery at the house. In the Museum notes it mentions that he ran a vaccination clinic on Wednesdays from 11am-12 noon. SLIDE 6: WHANGAREI, 1865 Here’s Whangarei, 1865. The St Andrews Presbyterian Church that the Clarke’s belonged to is on extreme right.1 The perfectly shaped volcanic cone of Mt Maungatapere is in the background. Volcanic hills are considered by the Northland Regional Council as one of the natural landscape features of the district. 1 Image from Florence Keene, Between Two Mountains: A History of Whangarei (Auckland: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, 1966) and captioned “Whangarei in 1865, showing Cafler’s home “Sans Souci,” the Whangarei Hotel, Walton Street and the Presbyterian Church on the extreme right. This is the earliest known picture of Whangarei [sic], p32. 4 SLIDE 7: KEY POINTS IN THE FAMILY HISTORY CONT. Now lets continue touching on the key points in The Clarke Family & Homestead Story… House Name: The origin of the name ‘Glorat’ is not known. One view is that it is named after the House of Glorat, which is the seat of the Stirling Family held since the early 1500s. Glorat is close to Campsie, England, where Alexander Clarke was born and raised. Architectural Style: “Built of kauri timber, with a galvanised iron roof and brick chimneys, the homestead has many of the attributes of a late Victorian New Zealand house.”2 Glorat is a large, 4 bedroom family house, “the doctor using part of it as a waiting room and surgery”3 and cost £720 to build. In contrast St Andrews Presbyterian Church cost £110 to build in 1861, just five years before.4 “The components of the house – boarding, flooring, lining, architraving, battens, cornices, drops, eaves, veranda posts, panelled doors, sash windows and frames can be matched with old catalogues sent out by the timber companies.”5 Richard Keyte built a local carpenter Glorat. Most of the furniture was also locally made. But we can’t trace the origins. Mim Ringer, the archivist says that it would be nice to learn that Mr Keyte made the furniture but there is no paper evidence in the form of receipts or notes to verify this. Public historian, teacher and Clarke Homestead founder Florence Keene in her 1966 book Between Two Mountains: A History of Whangarei, writes: “Richard and John Keyte came to Whangarei in 1865. They were carpenters by trade and their house and shop were near the 2 Mim Ringer, Information & History, Research Prepared for Draft Conservation Plan RE Clarke Homestead, Whangarei Museum 1994-2002 (Matapouri, January 2006), 33. 3 ibid. 4 Keene, Between Two Mountains, p256. 5 Ringer, Information & History: Clarke Homestead, p33. 5 corner of Cameron and John Streets. Richard later established an undertaker’s business”.6 Family History & Home Ownership: There is little information about Dr Clarke’s wife Mary except that “she found living conditions in New Zealand somewhat primitive”. It is noted that in this family story property passed between men and women. Dr Clarke’s second son, James, inherited the farm. In 1926 he established a small jersey cowherd. Reading between the lines, we learn that James was not an exceptional farmer; they simply produced enough milk, butter and cheese for the family. James Clarke era is a story about home renovations to meet a growing family; doors were removed and technology changed from gas lighting to electricity. When James died the property was handed over to his wife, Mabel, a local girl. In 1948 the property is inherited by Mabel’s oldest son, Basil, the third generation. Basil Clarke, bachelor and hoarder, marks the demise of the homestead and the beginning for a local museum & heritage park. The house becomes part of the Northland Regional Museum in 1973 and then in 1996 there is a name change to Whangarei Museum. 6 Keene’s book was written about the same time Whangarei outgrew being a small town and started life as a city, see F. Keene, Between Two Mountains, (p57). 6 SLIDE 8: ALEXANDER & MARY CLARKE’S GRAVESTONE Sadly Dr Clarke enjoyed his home for only a short period of time. On 26 July 1890 a note in the Northern Advocate stated that Dr Alexander Clarke was ill and confined to his house. Later that year Alexander travels to England seeking medical advice. The records are scant, but he returns to Maunu in 1891 a very sick man. Dr Clarke died at his home on 1 February 1892. He was buried on his property. When Mary died in 1915, 25 years after her husband, she was buried in the same grave as Dr Clarke. The grave is one of the sites of historical significance on the Heritage Park grounds. SLIDE 9: WE CAN LEARN ABOUT DOMESTIC WORLDS? So what can we learn? Curator and historian, Mim Ringer, says with Glorat, “remnants of bush and stone walls, trees planted by family, the house, shed at the back, stables and grave, carpets and wallpaper, furniture, paintings, photographs and papers remain background to the story.”7 So everything, big and little, from trees to seeds, plays a role in telling The Clarke Homestead Story. In addition to The Clarke Family Collection, museum records and work diaries, newspaper articles, and archive records help piece together threads of social history….where we learn about work, marriage and leisure. 7 Mim Ringer, Information & History: Clarke Homestead, p4 7 SLIDE 10: VOLCANIC STONES CLEARED FROM THE TERRAIN WERE USED TO FENCE PADDOCKS Whangarei District is well known for its volcanic stonewalls. Like other farmers in the region the Clarkes had to clear the land and used the volcanic stones to fence the paddocks. These stonewalls are part of Glorat’s unique character and are still maintained today. SLIDE 11: MARRIAGES – CREATING REGIONAL DESCENDENTS OF THE HOMESTEAD As noted earlier, over time the family continued to extend as they married into local families in the District. Most settled into farming. In 1906 Mabel Florence (nee Armstrong), married James Clarke, the second eldest son of Alexander & Mary Clarke. Mabel and James had four children: Doris born in 1908, Basil born in 1911, Joan born in 1916 and James Neville born in 1921. Myra Carter came to housekeep in 1923 and stayed with Basil Clarke until 1979 when she moved into a retirement home. Myra died in 1981. Although the property title was transferred to the Museum in 1973 Basil was allowed to live in the house until his death in 1983. Another wedding photo in the collection is of Kathleen Flora Clarke (nee Wilson), who married the eldest son, William Reid Clarke, in 1899. By selling some family property Kathleen and William were able to purchase farm land in Tuakau. 8 SLIDE 12: FRONT OF HOMESTEAD WITH FAMILY ON VERANDA: MARY, MABEL & BABY DORIS Again, from records, we learn that the family were fully involved in social occasions of the district. This included the A&P Society, the Maunu Anglican Church, the Maunu Tennis Club and the Women’s Institute. They also held dances, garden parties, wider family gatherings and afternoon teas on the property. From this picture you can imagine this garden becoming quickly overgrown and ‘haunted looking’ from neglect. 9 SLIDE 13: PART TWO – CREATING A HERITAGE PARK The story about the Clarke Homestead tells us much about the people at the time wanting to create this Heritage Park. In the 1970s, 1973 in fact, Glorat was purchased by the Northland Regional Museum, which later became the Whangarei Museum. The Museum, until that time, was housed in a building in the town centre. Like most small town museums, the rooms were dark and cramped, and the storage areas were too full. The museum needed a new home. When Basil Clarke indicated he was willing to sell Glorat and the surrounding farmland to the Museum the idea of a Heritage Park for the Whangarei District began to take shape. To provide a little bit of background to the history of museum and heritage park development in New Zealand, post WWII was a period of rapid museum building throughout the regions. In general Kiwis became interested in preserving and celebrating their settler history and figuring out what it meant to be a New Zealander. Ferrymead Heritage Park here in Christchurch, MOTAT, the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland, and Howick Historic Village are similar. This Heritage Park includes a full museum collection; a modest number of eclectic historic buildings such as the Whangarei women’s jailhouse, railway stations, the Riponui Pah School, the Hardie House and a red telephone box. All had their origins somewhere else in the Whangarei District. The Whangarei Museum & Heritage Park is home to 13 clubs including the Observatory, the Native Bird Recovery Centre, the Vintage Car Club, miniature trains, large gauge trains, vintage farm machinery and a radio collection. More recently the Northland Medical Museum moved its collection onto the grounds. The Heritage Park is a community facility; the grounds are hired out for functions and events. Visitors can go on bush walks. Here’s an aerial view of the 25-hectare property and of the homestead hidden by the Hardie House, Railway Club and Vintage Car Club buildings. This photo was taken in 1995. 10 SLIDE 14: Back of homestead. A garden was planted along the house. The original scullery was altered with additional windows. The water tank has since been removed. Dick Stirling, one of the founding members of the Heritage Park, kept a work diary. The diary is a valuable account of the amount of effort put into preparing the Homestead for exhibition, building facilities for Park visitors, and keeping up with land improvement. From Dick Stirling’s diary we learn that track maintenance was primary undertaken by the Dept of Corrections, and a large portion of his time was spent on tree felling and repairing stonewalls. SLIDE 15: TRAINING 18-MONTH OLD BULLOCKS The original idea was to have a working farm with regular “live days”. Bullock rides are part of the show. Again, volunteers raise and train the animals. SLIDE 16: CLEARING THE WILD GARDEN The wild garden originally between the house shed and the cowshed, was cleared by the museum to make a wide clear lawn. A garden was planted beside the shed and the telephone box sited at one end was moved to another location. 11 SLIDE 17: SHED AT BACK OF HOMESTEAD – PREPARING TO RENEW THE FOUNDATIONS This image is of the Shed at the back of homestead and the work involved in preparing to renew the foundations. The water tank on the right supplied the house; it was removed when the back yard was asphalted. SLIDE 18: CLARKE HOMESTEAD FLOOR PLAN Here’s an image of the Clarke Homestead Floor Plan. Rooms had different uses over the years. The living room was once Dr Clarke’s surgery; the waiting room was the front parlour. James and Mabel once used the second bedroom before becoming Myra, the housekeepers. Later Myra had a small room built off the kitchen. SLIDE 19: SECOND GENERATION CHANGES – JAMES & MABLE CLARKE 2nd generation improvements under James & Mabel Clarke involved making a new access between the kitchen and dining area of the living room. Other interior changes included installing an indoor toilet and bathroom in the 1920s. Theses changes probably had a lot to do with meeting the needs of accommodating four children and a housekeeper. Electricity was connected to the house and cowshed in the 1930s. Electricity may have changed the way lighting was used in the home, but heating continued to came from open fireplaces and cooking was done on a wood and coal range in the kitchen. 12 SLIDE 20: c 1950’s HOME IMPROVEMENTS – 3RD GENERATION BASIL CLARKE WITH HOUSEKEEPER MYRA CLARKE In the 1950s, the 3rd generation of the Clarke Family story, a modern enamelled iron stove replaces the old black iron range. Later, an electric stove is installed in the scullery. Post WWII, following the end of rationing, housekeeper Myra Carter, in a move to lighten up the kitchen, covered over the original dark varnish with mushroom coloured enamel paint. SLIDE 21: ‘Under museum ownership’: changes to front hallway mirrors volunteer activity Originally the wide front hallway narrowing through the archway to the passage to the back door was lined with furniture and pictures. These were removed in the 1990s when the doorways were glassed to allow unsupervised public access. This change coincided with a drop in volunteer numbers as the first generation of Heritage Park enthusiasts simply got too old. Florence Keene was an educator and public historian and was interested in interpretation; through her efforts she created a re-telling of the Clarke Homestead story. She embarked in volunteer recruitment who dressed in period costumes for museum visitors. Florence also wrote a guidebook about the Park and its collections. 13 SLIDE 22: VIEW OF GLORAT BY LOCAL ARTIST MIKE FERRIS IN FLORENCE KEENE, LEGACIES IN KAURI”, 1978 & LOCAL HISTORIOGRAPHY This image, View of Glorat, by Whangarei artist Mike Ferns is an idealised view of The Clarke Homestead & Heritage Park grounds and provides an insight into local historiography. Florence Keene writes social history with a 1970s sense of nostalgia and charm. About Mary Clarke she says “Gracious living was the keynote during this early period when the ladies of the house had regular “At Home” days, and visitors presented their cards to the maid before being conducted inside.”8 40 years later curator and archivist Mim Ringer makes the following observations about Florence Keene in The Clarke Homestead Conservation Report: “Florence Keene, as a teacher, provided reasonably structured lessons. In later years, visits became purely entertainment. Not that this is necessarily wrong, but a museum should have been presenting something more educationally satisfactory, given the substance of the material on hand. Florence Keene’s notes, in use for many years, became outdated.”9 In this local history drama Ringer firmly positions Keene on the cusp of education and entertainment and Keene’s public history publications are quietly sidelined. 8 9 Keene, Legacies in Kauri, p70. Ringer, Information & History: Clarke Homestead, p51. 14 SLIDE 23: MUSEUM ROUND GARDEN – A SHORT-LIVED EXPERIMENT, 1990S Not all of the Heritage Park dreams have been fulfilled however. In the 1990s some volunteers had the idea of re-creating a circular garden on the front lawn. Once constructed garden maintenance essentially became the undoing of the “good” idea. SLIDE 24: THE HAUNTED HOUSE TODAY The Haunted House today: This Regional jewel is situated in a broader Heritage Park, Museum & Kiwi House World… Whangarei Heritage Park’s point of difference is that it also has a collection of live native fauna. Namely kiwi, gecko, tuatara and the ruru, the native owl. SLIDE 25: COMMUNITY EVENTS, MATARIKI, JUNE 2011 It serves to draw in different community groups and hosts annual events, such as Matariki, the Maori New Year, as a way to make the museum come to life…. SLIDE 26: COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT The museum also runs education programmes on behalf of the Ministry of Education. Education and public programmes are supported by volunteers (who are usually retired teachers!). SLIDE 27: FRASER COLLECTION OF TAONGA FROM TE TAI TOKERAU, NORTHLAND The full museum collection includes a comprehensive and magnificent collection of taonga from Te Tai Tokerau, the Northland region. Known as the Fraser collection; at the time it was known as one of best private collections of Maori artefacts in New Zealand. According to Museum records, Mrs Fraser had stipulated in her will that the significant collection was to be held under the guardianship of Auckland 15 Museum until Whangarei District Council had built a fireproof museum.10 This didn’t happen until the 1980s. SLIDE 28: LIVE NATIVE FAUNA COLLECTIONS: GREEN GECKO The museum requires permits from the Department of Conservation for their live native fauna collections. Public advocacy is one of the mandates for holding these collections. These critters are sacred and often at the mercy of thieves. The museum has had a number of incidents over the years of gecko being stolen! SLIDE 29: NORTH ISLAND BROWN KIWI The North Island Brown Kiwi is the main draw card for children and tourists alike, it cohabitates with a ruru. SLIDE 30: JANE MANDER STUDY, C1908 Other significant buildings on the Park include the Jane Mander Study. Jane Mander is one of Northlands better-known authors. She lived in Whangarei for a while in the early 1900s and wrote from this tower; perhaps she’s best known for A Story of a New Zealand River, which Jane Campion based her film, The Piano, on. The film won the Palme d’Or Award in 1993. SLIDE 31: HISTORIC OBJECT BECOME A BACKDROP FOR WEDDINGS Today the Heritage Park is booked for weddings and Glorat House and grounds is often the backdrop in the photos. 10 Keene, Between Two Mountains, pp307-308. 16 SLIDE 32: PART THREE: HERITAGE SECTOR CHALLENGES Photo: Honorary Curator & Archivist, Mim Ringer, shows me a packet of exotic chilli seeds from the Alexander Clarke Collection. Mim is responsible for all the archival research on the Homestead. Her knowledge of the Whangarei District is extensive. Mim says that the Clarkes tried to grow everything and anything in the gardens – tea, tobacco, and chilli. They were curious to see what would take. Motivated partly by necessity, party by economic farming reasons, and partly by curiosity. Such biological experimentation was not unusual Settler behaviour. Gardening Historian, Christine Dann, says we know this as they kept journals and letters, wrote books and newspaper articles on plants and gardening, and founded horticultural societies. They brought with them a wide variety of English fruits, vegetables and herbs. The Clarke Homestead grounds have spectacularly large specimen trees that are over 100 years old. The garden collection includes a ficus and a hoop pine tree. The hoop pine was said to have been planted by a seed collected in 1902 when James Clarke attended a family wedding in Australia. Today the hoop tree’s branches are a hazard: they drop during high winds and the pine needles clog up the homestead guttering. A number of books are in Dr Clarke’s collection, like readers of his time, there was a deep interest in travel. A first edition of Captain James Cook’s explorations is on the shelf alongside Vancouver’s accounts and those of naturalist Dieffenbach. 17 SLIDE 33: VIEW OF THE HOUSE 1995 – CANDY POLE STRIPES! Museums and heritage parks are heavily reliant on volunteer labour, donations, gifts, and funding. Funding comes from many sources, such as local government, the Ministry of Culture & Heritage, Pub Charities and other philanthropic groups. This is a highly contested and competitive market; it can take 5-10 years before a funding application may be successful, or if successful, there is usually a short fall in funds. The story of the candy pole stripes is fascinating. At some stage, after the circular garden, volunteers painted on and then painted over these stripes, which are not particular to any historical period! SLIDE 34: CONSERVATION IN SLOW MOTION The Clarke Homestead was recently granted $5,000 from the Sir John Logan Campbell Residuary Estate, to replace the roof iron. While exciting to receive the funds it was frustrating as we were only able to get one side of the veranda roof iron replaced. One day the other 3 sides of the veranda as well as the roof iron will also be replaced. I just hope it’s soon; the roof has too many holes! This leads us to the bigger question of how to conserve and maintain the historic homestead and other items in the heritage park and museum collection. Sadly there are far too many objects and buildings on this 25hectare property. As for the Homestead, does anyone want to guess approximately it will cost to restore this house? 18 Answer: $250,000 Work needed includes: Replacing the piles; Replacing the roofing and finding someone who had the right tools to bend the veranda iron; Installing a sprinkler & alarm system; Solving the water pressure problem; replacing rotten exterior wood cladding; replacing the guttering, and repainting the exterior; Museum conservation requirements include: o installing new dehumidifiers & purchasing conservation materials for the collection items in storage; new display cases are also on the wish list; o and the wallpaper billows from the wall like a sail and urgently requires conservation work. Finally, there is also the idea of creating interpretation story boards to enhance to visitor’s experience. Northland is such a wet, moist landscape. It rains every day, humidity is high, and things go mouldy, cotton rots quickly. Such conditions place a stress on the homestead and its collection. The Heritage Park is on extensive bush and farmlands; rats are a common nuisance. The Park is reliant on funding from the Northland Regional Council for rat and possum traps, which are monitored by a volunteer. The number of rats caught, and rabbits and possums shot, are recorded and annually reported back to the Regional Council. 19 SLIDE 35: OBJECTS BECOME A PUBLIC DANGER Metal, if left exposed, also decays over time. This steam engine had been on display in the Park grounds for over 30 years. While children are encouraged to explore and climb in the Park this object had become a health & safety risk if touched. After much consultation the engine was de-accessioned from the museum collection and sent to the scrap yard; this returned $2,000 back to the museum and converted into roof iron for the Clarke Homestead. SLIDE 36: CONCLUSIONS In today’s talk we’ve traced the origins of a family home, which was built in 1886 and later became known as the haunted house. In the 1970s it was transformed into a Museum and heritage building. In becoming a museum certain challenges have been presented, namely: (i) How to interpret local histories: or sorting fact from local mythology. For example in 1978 local historian Florence Keene wrote in her book, Legacies in Kauri: old homes & churches of the North, “Glorat was built of kauri and has had such loving care from successive members of the family that most of its original furniture, its large-patterned wall paper and its carpets have been preserved in remarkable condition” (p70). Keene may have been optimistic in her assessment of the “remarkable condition” of some parts of the homestead. Objects and buildings do age with time. However, by 2006 museum curator and archivist, Mim Ringer noted “over the years, periodic deterioration of the iron roof dating from the very early years, allowing leaks on to [the] wallpaper.”11 (ii) Other museum challenges involve how to manage collections: Again, Mim Ringer writes, “from its inception as a museum, many objects unrelated to the Clarke Family have been introduced, such as the Hewlett piano, the Edison gramophone, several chairs, books and much bric-a-brac [such as lace doilies and home preserves]. The majority of items have been identified.”12 Yet later in the report Mim also says “the non-Clarke family 11 12 Ringer, Information & History: Clarke Homestead, 52. Ibid, p39. 20 artefacts introduced from the earliest days of the homestead as a museum, have rarely been differentiated, becoming part of the intrinsic ‘mythinformation’ that is the public story.”13 Sorting fact from re-creation is still a challenge today. (iii) The final challenge is about how to create “significance” and generate revenue. The property is owned by a Charitable Trust and needs to cover its operating costs as well as keeping up with extensive maintenance of the grounds, buildings, facilities and collections. Overall, it is the ordinariness of this house that makes it so unique. It’s a regular 4-bedroom kauri villa; the materials and style were typical of the period and the region and for the social class of the original owner, Dr Alexander Clarke. Now the Clarke Homestead has become the District’s treasure. As a NZHPT listed house situated within a Heritage Park its future is protected. It serves as a springboard for family history storytelling and it has the most magnificent views! So what do we learn through the Clarke Homestead Story? In my view, through the Clarke Homestead Story we learn as much about a local region’s history as we do about certain individuals who each had a vision of what this heritage wonderland would be, and how this vision has shifted over time.... 13 Ibid, p52. 21 SLIDE 37: SOURCES & QUESTIONS? Christine Dann, Cottage Gardening in New Zealand (Wellington: Allen & Unwin in association with the Port Nicholson Press, 1990). Florence Keene, Between Two Mountains: A History of Whangarei (Auckland: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, 1966). Florence Keene, Legacies in Kauri: old homes & churches of the North (Northern Publishing Company: Whangarei, 1978) Mim Ringer, Information & History, Research Prepared for Draft Conservation Plan RE Clarke Homestead, Whangarei Museum 1994-2002 (Matapouri, January 2006) Clarke Homestead Collection: Letters Alexander Clarke to brother James McLean Clarke, May 1882-May 1884; Family photograph albums Whangarei Museum records: Dick Sterling work diary, Whangarei Museum & Heritage Park c1970s Interview: Mim Ringer, Archivist and curator, Whangarei Museum, July 2010 Newspapers: Northern Advocate END 22