Our Greatest Want: An Examination of the Rhetorical Tendencies Employed by African American Female Abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

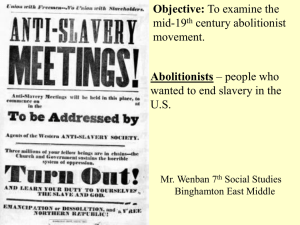

advertisement