12658308_2014 03 28 Pilocarpine results paper v33SCC.docx (49.12Kb)

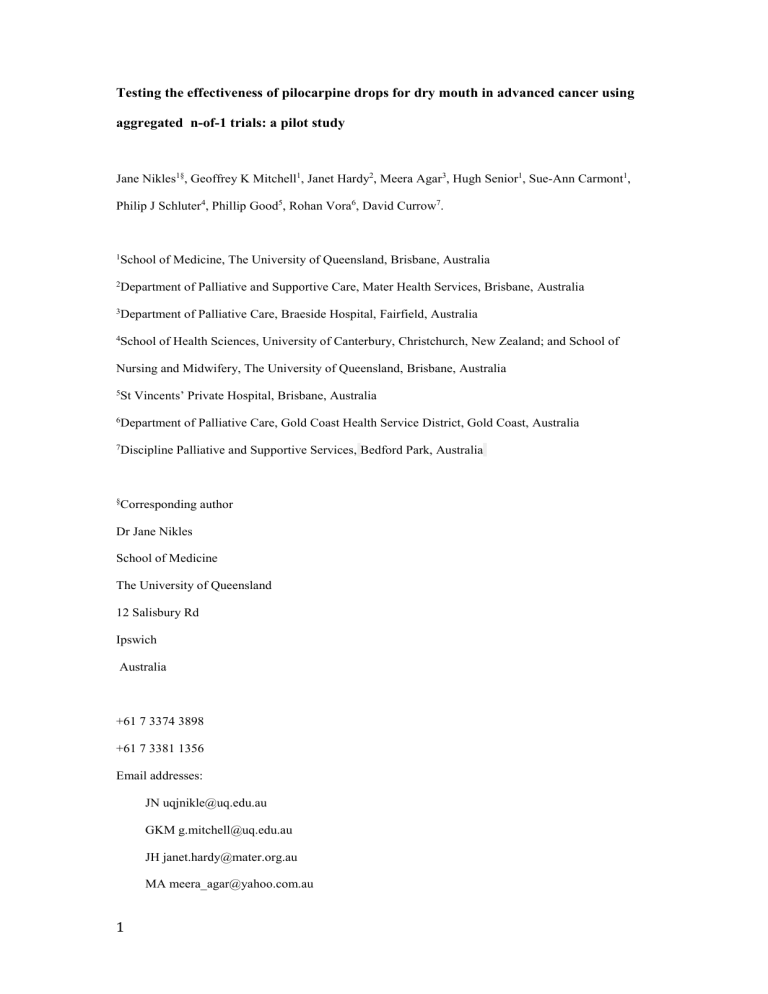

Testing the effectiveness of pilocarpine drops for dry mouth in advanced cancer using aggregated n-of-1 trials: a pilot study

Jane Nikles 1§ , Geoffrey K Mitchell 1 , Janet Hardy 2 , Meera Agar 3 , Hugh Senior 1 , Sue-Ann Carmont 1 ,

Philip J Schluter 4 , Phillip Good 5 , Rohan Vora 6 , David Currow 7 .

1 School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

2 Department of Palliative and Supportive Care, Mater Health Services, Brisbane, Australia

3 Department of Palliative Care, Braeside Hospital, Fairfield, Australia

4 School of Health Sciences, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand; and School of

Nursing and Midwifery, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

5 St Vincents’ Private Hospital, Brisbane, Australia

6 Department of Palliative Care, Gold Coast Health Service District, Gold Coast, Australia

7 Discipline Palliative and Supportive Services, Bedford Park, Australia

§

Corresponding author

Dr Jane Nikles

School of Medicine

The University of Queensland

12 Salisbury Rd

Ipswich

Australia

+61 7 3374 3898

+61 7 3381 1356

Email addresses:

JN uqjnikle@uq.edu.au

GKM g.mitchell@uq.edu.au

JH janet.hardy@mater.org.au

MA meera_agar@yahoo.com.au

1

HS h.senior@uq.edu.au

SAC s.carmont@uq.edu.au

PS philip.schluter@canterbury.ac.nz

PG Phillip.Good@stvincentsbrisbane.org.au

RV Rohan_Vora@health.qld.gov.au

DC david.currow@flinders.edu.au

ABSTRACT

Purpose

Dry mouth is a common and troublesome symptom in palliative care. Pilocarpine is a cholinergic agent that promotes salivation. We aimed to test the effectiveness of pilocarpine drops compared to placebo, for participants with advanced cancer, who experienced dry mouth.

Method

Aggregated n-of-1 trials for patients of specialist palliative care services with advanced cancer assessed as having a dry mouth. Each participant was offered three cycles of pilocarpine drops 4%, 6 mg tds (3 days) and placebo drops (3 days) in random order. Patients self-completed a diary using validated symptom and quality of life scores. The randomisation order was unmasked at the end of each person’s trial by a clinician independent of the trial to allow a treatment decision for individual patients to be made.

Results

Twenty people were recruited to this pilot study, of whom five completed the planned three cycles; 36 cycles of data were completed in total. 438 doses of pilocarpine were administered. Most withdrawals related to deteriorating condition, unacceptable toxicity, non-compliance with study procedures or withdrawal of consent. Overall, no clinical

2

difference in relief of dry mouth was noted on two measures of dry mouth, and an oral health related quality of life scale.

Conclusion

The formulation of pilocarpine drops proved unacceptable to most participants. More work is required to determine an appropriate dose and method of delivery, then a retest of pilocarpine drops for this symptom.

Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry Number: 12610000840088

Key words: pilocarpine, n-of-1 trial, palliative care, xerostomia, advanced cancer

Word count

Abstract 205

Main text 2079

3

Background

The gold standard of proof that an intervention works is the randomized controlled trial

(RCT). One critical component to the success of RCTs is recruitment of a predetermined number of participants to adequately power the study. Achieving this is often challenging, but is feasible where the pool of potential participants is large or the eligibility criteria broad and inclusive. It can prove very difficult to achieve in certain populations where the patient pool is small, or patients are hard to recruit or retain. Palliative care (PC) is often such a clinical situation [1].

Alternative methods of conducting trials in these situations need to be explored. One alternative method is aggregated n-of-1 trials. N-of-1 trials are within-patient, multiple crossover, double blind randomized controlled trials, using standardized measures of effect.

Standard n-of-1 studies have the advantage of providing individualized results to participants immediately after the trial ceases, which provide guidance for clinical decision-making as to whether to continue the treatment or not. They have been used for decades to determine whether treatments work in individuals in a range of settings [1]. They are suitable if the treatment to be tested has a short half-life and has a rapid onset and offset of action, is treating a symptom in an underlying clinical state which remains stable over time, and the question is clinically important [2].

Individual n-of-1 trials can be aggregated to provide a population estimate of effect, with equivalent strength to a conventional two-group RCT. This can be achieved with a fraction of the sample size required to conduct a parallel arm or single cross-over RCT [2-4]. The methods are discussed in detail in Nikles et al. 2011 [2], Zucker et al (1997)[3] and Schluter and Ware (2005)[4].

4

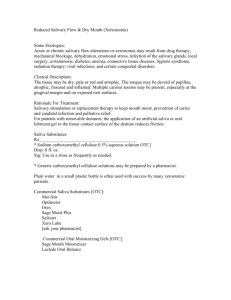

Dry mouth (xerostomia) is a troublesome symptom in patients suffering from advanced cancer. Current treatments include artificial saliva substitutes, mouthwashes and treatment of coexisting infections such as oral candidiasis [5]. Pilocarpine is a cholinergic agent mainly used in the treatment of open angle glaucoma. Pilocarpine stimulates salivation through the parasympathetic nervous system. Pilocarpine is an ideal treatment for n-of-1 methodology; its half-life is 0.76 hours, there is an immediate effect on salivation, and the effect wears off rapidly, fitting all of the criteria outlined above [6].

Given that the systemic side effects of cholinergic agents are often unpleasant, we sought to determine if the use of topical oral pilocarpine would produce salivation in the absence of significant systemic side effects. We found only one existing trial of pilocarpine tablets in PC patients [7]. Although pilocarpine was found to be more effective than artificial saliva in terms of mean change in visual analogue scale scores for xerostomia (P = 0.003)[7], further trials are warranted. We aimed to conduct a pilot study of the effectiveness of pilocarpine drops 4%, 6 mg tds compared to placebo, for participants with advanced cancer, who experienced dry mouth, using aggregated n-of-1 trial methodology.

Methods

The methods have been previously described [8]. Briefly, the trial consisted of up to three cycles, each cycle comprising three days each of placebo and active medication in random order – a total of eighteen days. The randomisation sequence was computer-generated and applied by the study pharmacy. Patients, physicians and research assistant were blind to medication order.

Setting

The trial was conducted in seven palliative care units in Queensland and New South Wales,

Australia. Ethics approval was provided by each participating hospital and by the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia.

5

Trial medication was 6mg of active pilocarpine hydrochloride drops (4% or 40 mg/ml), or identically flavoured placebo (citrus flavor) in random order, three times daily with meals.

The patients administered the drops themselves unless assistance was required from a nurse.

To account for washout between cycles, the data from day one of each treatment period was discarded, with the data from days two and three of each three day treatment period being analysed.

An individualised report was sent to the referring doctor at the completion of the patient’s trial to inform ongoing pilocarpine treatment decisions without trial staff being aware of the findings.

Participants

Participants were adult patients with advanced cancer, and dry mouth (defined as having a score of

3 on an 11-point xerostomia numerical rating scale (NRS)), who had no known allergy to pilocarpine and could complete all trial requirements.

1.

2.

1.

Patients were excluded if there was any plan to change any medication with the potential to cause dry mouth or to undergo any intervention (e.g. radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgery) that might alter dry mouth symptoms during the study period, ocular problems contraindicating the use of parasympathetic agents (eg irido-cyclitis, increased intraocular pressure);

2.

other comorbidity where there was a risk of worsening co-existing medical problems during the trial period and/or active treatment was contemplated or an active oral

6

infection (e.g. candidiasis, herpetic infections, mucositis, mouth ulcers).

Patients who discontinued the study for whatever reason were able to resume the trial if their condition could be re-stabilised for at least one week. Patients who could not resume the trial had their completed cycle results added to the trial dataset for later calculation of the population effect of pilocarpine. If a patient’s withdrawal from the study was attributed to the intervention, their data contributed to the analysis under the intention to treat principle.

Measures:

The primary outcome measure was xerostomia NRS score for dry mouth on average in the last 24 hours. This is an 11-point scale between 0 and 10, with a lower score indicating less dry mouth. While there are no validated scales for xerostomia, NRS are widely used, valid and reliable [9]. Secondary measures included the mean Xerostomia Inventory Score [10], the

Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) [11] and Patient Global Impression of Change score [12].

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and dysgeusia (altered taste) were assessed using NRS scales. Side effects were recorded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology

Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTC AE) v3.0 [13].

The Australian-modified Karnofsky Performance Scale assesses functional performance on a scale from 10-100 [14]. It is valid and reliable, and demonstrates change in function reliably as the end of life approaches. This was used to assess the patient’s functional stability over the course of the trial.

Sample size

The rationale for the sample size calculation is presented in detail elsewhere [6]. In total, 70 patients were to be recruited, with 31 (44%) patients expected to complete all 3 cycles, 4 (6%) to complete cycles I and II, 7 (10%) to complete cycle I only, and 28 (40%) to complete no cycles.

7

A clinically significant response to pilocarpine was defined as a ≥2 point improvement in xerostomia NRS score compared to placebo. This is in view of previous work, where a

20% (2 cm) improvement or more against the baseline score was considered to be a positive improvement [15,16].

Analysis

The effect of pilocarpine was assessed for each participant individually, by determining whether pilocarpine relieved dry mouth more than placebo in each of the three cycles.

The participant was assessed as a probable responder to pilocarpine if all three cycles favoured it; a possible responder if two of three cycles favoured pilocarpine; and a likely non responder if one or no cycles favoured pilocarpine. NRS data was collected on days 2 and 3 of each cycle pair to allow medication wash-out during day 1.

To calculate the individual and aggregated effect of pilocarpine on dry mouth in this population, hierarchical Bayesian methods were employed using normal likelihood functions, and noninformative priors, following the method described by Zucker and colleagues [3].

Posterior mean treatment differences (defined as Active – Placebo scores), 95% credible regions (CRs), defined by the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles of the posterior distributions, and posterior probabilities that the mean difference was greater than 0 were calculated [3].

Results

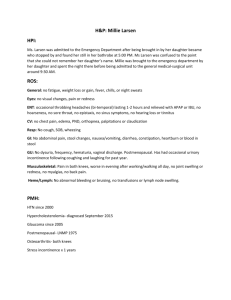

We recruited 20 patients from March 2011 to December 2012. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are noted in Table 1. Of these, ten participants (50%) completed one cycle, five (25%) completed two cycles and five (25%) completed all three cycles (but one had incomplete data for cycle three) so there were 4 completers with complete enough data sets to analyse (20%). Two patients (10%) commenced the trial but withdrew before

8

completing data for any cycles. 438 doses of pilocarpine were administered. Figure 1 shows patient flow. For the xerostomia NRS, 4 (20%) patients completed valid assessments for all 3 cycles; 5 (25%) patient completed 2 cycles; 9 (27%) patients completed 1 cycle, and 4 (20%) did not complete valid xerostomia assessment for any cycles.

The main reasons for withdrawal (Figure 1) were deteriorating condition (5), withdrawal of consent (4), unacceptable toxicity (3), noncompliance (2), hospital admission (1). Side effects were nausea (3), headache (1), visual disturbance (1) (one person withdrawing consent experienced two symptoms), all graded at 1-2 out of four using the NCI CTC AE v3.0 [13].

(Grade 1 means mild; asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated; Grade 2 means moderate adverse event). Some patients described unacceptable taste or excessive salivation to research staff. These could not be categorised by the NCI CTC AE criteria. Two serious adverse events occurred, both unrelated to the trial: one patient died from radiation-associated pneumonitis and the other was admitted to hospital for side effects of concurrent non-trial medication.

Pilocarpine did not affect dry mouth on the NRS (mean difference -0.9 (95% CR: -3.9, 2.0); posterior probability mean difference less than zero = 0.75) or the Xerostomia Inventory

(mean difference 0.3 (95% CR: -3.7, 2.9); posterior probability mean difference greater than zero = 0.65). The OHIP score was not altered by the use of oral pilocarpine drops (mean difference -0.4 (95% CR: -1.8, 0.8); posterior probability mean difference greater than zero =

0.23).

Discussion

Although this trial did not meet its recruitment target within the granting body timeline, some important lessons were learned, namely the time, cost and difficulty involved in obtaining ethics and governance approval at seven sites, and the challenge of meeting time lines in terms of recruiting to palliative care trials.

9

Our results cannot be interpreted as evidence that pilocarpine does not work in this situation, because the realized sample size fell well short of the estimated needed sample size, and because of the likely effect of differential attrition.

N-of-1 trials have been successfully applied previously in a palliative care population [17].

Dry mouth is a common problem in people with advanced cancer and thus it was surprising to find recruitment so difficult for this trial, and that the withdrawal rate was very high.

Anecdotally, the taste was an issue for some patients. We tried different masking agents

(peppermint, raspberry), and tested the taste with people not suffering from advanced cancer.

The taste was acceptable for these people, raising the possibly that the altered taste sensation that arises from cancer and its treatment may deleteriously affect the taste of masked pilocarpine drops. There were also other challenges in conducting a trial with a non-standard medicine – active and placebo production by manufacturing pharmacies, and licensing across states and institutions. Further, as taste is not a criterion recognized by NCI CTC AE criteria, it is likely that this cause for withdrawal was not identified in the data collected.

We chose to administer the drops orally for two reasons. The first is that orally administered tablets have side effects that impact on the whole body. We considered that direct delivery by drops into the mouth would be more acceptable, and reduce both the dose and the side effect burden. Drops are also easier to procure in Australia where pilocarpine eye drops are available as a general benefit on the government-supported Pharmaceutical Benefits

Schedule, but the tablets are not. Clearly further work needs to be done to determine the best mode of delivery and the most effective dose, followed by a sufficiently powered trial.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

10

Authors' contributions

JN, GM, DC and JH conceived the study. All authors contributed to study design. JN drafted the manuscript. PS provided statistical advice and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cancer Council Queensland for providing funding, and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) for providing an NHMRC post-doctoral research fellowship 401780 for Jane Nikles. The funding body had no role in writing the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

11

References

1. Gabler NB, Duan N, Vohra S, Kravitz RL.

N-of-1 trials in the medical literature: a systematic review. Med Care. 2011 Aug;49(8):761-8.

2. Nikles J, Mitchell GK, Schluter P, Good P, Hardy J, Rowett D, et al. Aggregating single patient (n-of-1) trials in populations where recruitment and retention was difficult: the case of palliative care. J Clin Epidemiol . 2011 May;64(5):471-80. PubMed PMID: 20933365.

Epub 2010/10/12. eng.

3. Zucker DR, Schmid CH, McIntosh MW, D'Agostino RB, Selker HP, Lau J.

Combining single patient (N-of-1) trials to estimate population treatment effects and to evaluate individual patient responses to treatment. J Clin Epidemiol.

1997. 50 (4):401-10.

4. Schluter PJ, Ware RS. (2005). Single patient (n-of-1) trials with binary treatment preference. Statistics in Medicine , 24 :2625-2636.

5. No authors listed. eTG (e Therapeutic guidelines) complete. Ltd. TG, editor. North

Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines; 2013.

6. No authors listed. Oral pilocarpine: new preparation. Xerostomia after radiation therapy: moderately effective but costly. Prescrire Int . 2002;11(60):99-101.

7. Davies AN, Daniels C, Pugh R, Sharma K. A comparison of artificial saliva and pilocarpine in the management of xerostomia in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med .

1998;12(2):105-11. PubMed PMID: 9616446.

8. Nikles J, Mitchell GK, Hardy J, Agar M, Senior H, Carmont S, Schluter PJ, Good P,

Vora R and Currow D. Do pilocarpine drops help dry mouth in palliative care patients? A protocol for an aggregated series of n-of-1 trials. BMC Palliative Care 2013 Oct 31;12(1):39.

9. Sindhu B, Shechtman O, Tuckey L. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of a digital version of the visual analog scale. J Hand Ther 2011;24(4):356-63.

10. Thomson W, Chalmers J, Spencer A, Williams S. The Xerostomia Inventory: a multiitem approach to measuring dry mouth . Community Dent Health . 1999;16(1):12-7.

12

11. Baker S, Pankhurst C, Robinson P. Utility of two oral health-related quality of-life measures in patients with xerostomia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006;34:351-62.

12. Hurst H, Bolton J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004;27:26-35.

13. National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health: Common Terminology

Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). Publish Date: August 9, 2006.

[ http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf34/35].

14. Abernethy AP, Shelby-James T, Fazekas BS, Woods D, Currow DC. The Australiamodified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice [ISRCTN81117481]. BMC Palliat Care . 2005 Nov 12;4:7.

15. Kasama T, Shiozawa F, Isozaki T, Matsunawa M, Wakabayashi K, Odai T, Yajima

N, Miwa Y, Negishi M, Ide H. Effect of the H2 receptor antagonist nizatidine on xerostomia in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Mod Rheumatol 2008. 18:455–

459.

16. Furness S, Worthington HV, Bryan G, Birchenough S, McMillan R. Interventions for the management of dry mouth: topical therapies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011.

7(12):CD008934.

17. Hardy J, Carmont S, O’Shea A, Vora R, Schluter P, Mitchell G, Nikles J. Pilot study to determine the optimal dose of methylphenidate for a single patient trial of fatigue in cancer patients. J Palliative Medicine.

(2010) 13 (10):1193-1197.

13