Social Aspects of Story Exchange: Abstract

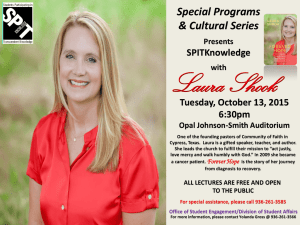

advertisement

SOCIAL ASPECTS OF STORY EXCHANGE: ABSTRACT Joann Bromberg In a study of social conversation I have found that placement of one story next to another describing a similar experience, alters the emotional impact of the first story. As Harvey Sacks argued, the “second” works to generalize the first. It feels bigger, grander, less particular or idiosyncratic than before. This finding led me to consider alternative instances, also commonplace in conversation; times when a “first” storyteller is not reciprocated with a second story but rather, greeted differently: with laughter, with a move to change the topic, or with silence. By looking at different types of response (how do listeners bring conversation forward?) one can trace “pattern in meaning” through the juxtaposition of choices. Here we look at how the personal story helps a group member identify with and separate from others. We see how her choice to tell or withhold a story may effectively include or exclude other(s). And we see how an exchange or the refusal to exchange a story and enable or disable participants’ effort to maintain or change their shared worldview. To illustrate, I present four examples, all drawn from tape-recorded conversation generated by the same group of women. (1) “Inviolable Time,” viewed by listeners as a “good” story and greeted by laughter, is compared with (2) “The Nasty Woman Boss,” a story which elicits no response and is followed by a move to change the topic. These examples are then contrasted to two others, both receiving a second story response. (3) “Do You Talk to Mother about Work?” is a minimal exchange where agreement and disagreement is expressed but then the topic is abandoned. (4) “ That Way of Thinking” is an elaborate exchange during which two fully realized stories are presented and the subject of those stories (you think his work is more important than your own) is considered in depth. Amid this exchange, members’ become familiar with intimate material and witness one participant’s “aha” moment of awareness, when her view of self and world shifts. Examples (1) and (4), hold certain thematic elements in common as do (2) and (3). By highlighting and distinguishing these commonalties, we see how participants direct and monitor cultural change through everyday social talk. SOCIAL ASPECTS OF STORY EXCHANGE: ILLUSTRATIONS (1) INVIOLABLE TIME April 11, 1973. Laura A teacher of mine told me a funny story about his wife. She was working on her dissertation. Which she finished way after he finished his. She was like supporting, them, through that. Anyway, she was working on it so she set aside Inviolable times when nobody in the house was allowed to disturb her. And one day she was in one of her inviolable times and he was cleaning the windows on the third floor. Which is very gablely. And, anyway, he got himself out the window. And then something slammed closed and he was like hanging there on the window frame from the third floor room and Just hanging on! So he screamed and he screamed and he screamed and finally she came. Opened the door and said, don’t you know this is my inviolable time, and Slammed the door and left! All five of us erupt in raucous laughter. JoAnn Laura JoAnn Laura JoAnn Laura You’re kidding! I am not kidding! Well. What did she do? Eventually she came back. How much later? I don’t know. That’s incredible! Once again, we explode with laughter. This wife’s bold defiance of convention, her code-breaking behavior no matter the circumstance, delights me. Predictability, thrown awry. I am, in fact, astonished by the audacity of this wife who recognizes basic needs so clearly that she sets aside required time, apart from others, at home, for work. For a fleeting moment I can glimpse my own “go to the rescue” mentality. That deeply ingrained sense of moral obligation: others call, I come. No one says a word about that teacher, left stranded, hanging by fingertips, high on that gabled, three-story, mansard-roof townhouse, waiting for his wife to come to the rescue. That the husband lived to tell the tale, that he told it with relish to his student, that Laura retold it to us with such pleasure, probably helped keep the standard “how could she do that, to him?” reaction from setting in. That Laura didn’t know how long he was left hanging, that the wife’s return was irrelevant, that Laura didn’t ask, didn’t care, all played a part in sharpening this Inviolable Time story, paring it, home. That’s a beautiful story. I’m going to tell that story. We have that on tape. JoAnn Sarah There it is, I think to myself, folklore-in-the-making. The golden nugget folklorists are trained to look for, captured as told within the conversational world of my consciousness-raising group. Variants of the Inviolable Time story crop up again, on subsequent evenings. In this way we acknowledge the story’s impact and illuminate our different way of thinking. Repetition cements the story’s value. Years after the group disbanded, it dawned on me that over the course of nine months together, we exchanged only a handful of “good” stories in my group. “Inviolable Time” was a delightful exception. For the most part we told versions, some detailed, more truncated, of commonplace I know what you mean experience. As I thought about this salient aspect of consciousness-raising, how the embedded stories were so different from commonly collected narratives typically referred to as “folklore,” I realized that for our purposes funny, performed, remembered good stories - - welcome or unwelcome - could prove a distraction. In a group such as ours, where restructuring relationships was the goal, poring over similar, mundane experience (some would call it trivial) enabled learning. How else could we have changed what we expected of ourselves? (2) The Nasty Woman Boss March 14, 1973 Jill I’ve been ( ), where several people are working. Mostly women, with the big desk up at the head, Presided over by a man. And there was this one woman in there that I had to see because her name was on the paper I had gotten, although that was just a form letter and it could be from someone else. But she was a classic example of a woman trying to out-power a man or whatever. Because she was rude to everybody in the same way I’ve heard men be to women in the office. Rough, you know. (0.1) Elegantly clothed, business suit. Just looking like, you know, success, efficiency. But just treating everyone like, speaking loudly and. JoAnn Right. Jill I got the feeling that she, thought if herself, the only way she could get ahead was to imitate all the things we consider negative, you know. (0.2) It just kind of hit me cause we were talking about that before. (0.3) Laura (to JoAnn): How do you, how would you describe yourself? (0.2) (3) MOTHER, AND WORK June 27, 1973 Deborah JoAnn Deborah Laura Do you really talk to you mother about your work? I don’t. Do you? ‘Cause, my mother always says, you know, How’s school? And I say Great! And she says something like, you know, You can’t have a family and teach school too. That’s sort of where we get. Feelings about, work And feelings like about getting a degree and looking for a job or being dependent or independent. That kind of thing. Yeah. I do talk about that with my mother. (4) THAT WAY OF THINKING March 14, 1973 Laura What about you, and power? Rachel Most of my power I get from threatening. Of being threatening by being aloof. Or kind of mean, Or by guilt. The one is when I’m feeling confident of myself I can be overbearing and kind of, you know Too busy to bother with people Or I can scare a lot of people. And when I’m feeling like I’m on the wrong end of it I use guilt. You know, two standard weapons. JoAnn I do that too. Rachel Well, actually, it’s interesting. It goes hand in hand with having handed over power. Like I acquiesce on the decision and then sort of act as if Oh well, it’s all your responsibility now and I’m not going to like what comes of this. And that’s the way I sort of seek to get back some kind of leverage. By making the other person, fellow Sorry that he took power away from me. Or took the decision away from me. Or that I gave up the decision. (We prod. Be more specific, more personal: Could you give an example.) I end up spending a lot of time at Don’s. I’ve agreed to that. I’d say, all right, we’ll do it your way And then I’d just go and sulk. Here we are… The burden is on you. If you don’t act appreciative enough I can always bring it to your attention. I am here as a sacrifice to you. Laura You mean, since his work is more important than yours, in your eyes, you’ve agreed to this. Rachel Yeah. It’s that kind of thinking. (We wait.) I think there’s less difficulty for me to do that than for him to do the opposite. (He is a graduate student, in Classics.) Laura It would be less difficult for me to give up a Ph.D. than for Will to wait two years. Sarah. What if you just alternated? Rachel It used to be a much bigger problem than it is now. Well, I used to mind it a lot more. (She laughs. Two staccato, low pitched, gravelly barks.) I don’t mind it as much now. (softly) Oh . . . Rachel! Stop it. Please! (crying) Yeah, When I said that, all of a sudden, the answer came tripping out of my mouth. And I thought, I’m going to catch hell for this. Laura Rachel Laura (blowing her nose.) It’s very hard to stop. Cause you’ll really get to believe that that’s the way it’s supposed to be. Joann Right, You both do. Deborah I did that so much. I really did it so blindly. I still get mad about it. There was a real basic fear that if I didn’t . . . he wouldn’t come. That he didn’t care enough, that I wasn’t important to him enough . . . Unless I was there. And so it was up to me To get us together… But afterward. God! I was ashamed of myself for it. How could I have ever done that and how could I ever tell anybody. You know, I wouldn’t want anybody to know I did that.