Publication in PDF format

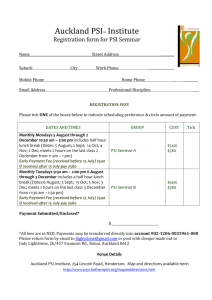

advertisement