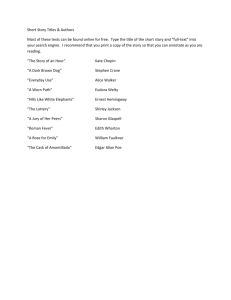

12658875_An American Witness-final.docx (41.18Kb)

advertisement

An American Witness: Edith Wharton and World War One Maureen E. Montgomery NZHA Conference Christchurch, 4 December 2015 On this day, a hundred years ago, the American writer, Edith Wharton, received a telegram from Henry James’ amanuensis informing her that “the Master” had had a stroke, leaving him paralyzed. Wharton had last visited James in England in the previous October, at a time when his health had begun to deteriorate significantly and he was not the old Henry that she had come to love and admire. Since the outbreak of the war, she had been sending him detailed letters of her activities in France, keeping him posted of developments and sharing with him the horror at unfolding events and their belief that what they were witnessing was the “crash of our civilization” (Powers, Letters 289). When he responded to letters she wrote him after visiting the Western Front, he told her that her “whole record is sublime, and the interest and the beauty and the terror of it all have again and again called me back to it.” In fact, he wrote that he knew her “incomparable pages” by heart. James was much in awe of her seemingly inexhaustible energy, but in that December Wharton was taking an enforced rest in the French Riviera, “smell[ing] the eucalyptus & pines, & arrang[ing] bushels of flowers bought for 50 centimes under a yellow awning in a market smelling of tunny-fish & olives—” (Lewis and Lewis, Letters 361-62). There was nothing new about Wharton oscillating between periods of prodigious activity and prostration. It was very much the pattern of her life. As a woman of means who also earned a considerable income from her fiction, she was able to take her rest 2|Page An American Witness cures in the choicest resorts and spas of Europe. Within days of the outbreak of war she had thrown herself wholeheartedly into philanthropic work in Paris, responding to the immediate needs of unemployed French women workers and Belgian refugees. To give you some idea of what she threw herself into, here is a list of her war-relief activities in just the first 15 months of the war: In August 1914 she established a workroom in Paris for women who had no other means of support, where they made bandages and men’s shirts, knitted socks and gloves, and even sewed “fine lingerie”; In November 1914 she collaborated with friends to set up the American Hostels for Refugees, a charity which not only provided food and shelter to some of the thousands of Belgian refugees pouring into Paris in the early weeks of the war, but also medical services, classes for children, a nursery, as well as helping refugees find paid work; Between February and August 1915 she undertook five trips to the Front in her chauffeur-driven Mercedes to report on the state of hospital services and to take supplies; In the spring of 1915 she was approached by the Belgian government if she could take “care of orphaned and abandoned children from Flanders”; this request led to the establishment of the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee which, in addition to running homes for over 600 children, housed “another two hundred aged and infirm Flemish adults,” as well as providing the children with jobtraining (Price ix-xi). All of this required strenuous effort on her part to raise funds to keep her various charities going, which she did through writings hundreds of letters to friends in her extensive social network and writing articles for the American press, publicizing the 3|Page An American Witness plight of displaced French and Belgian civilians and the need for medical and other supplies for Allied troops. In addition, in 1915 she edited a book of illustrations, poems and short stories by famous artists, and translated items from French. Entitled The Book of the Homeless and published by Scribner’s, it was auctioned in New York to raise money for her charities. She claimed in her memoirs that she scarcely had any “freedom” during the war years for writing (A Backward Glance 1046). Just as she deprecated her philanthropic work, false modesty prevented her from admitting her war-time literary output – prodigious given the circumstances (Olin-Ammentorp, Edith Wharton’s Writings 1-2). Among these we can point to 37 items for magazines and newspapers, including poems, articles about and appeals for her war charities, and essays describing wartime Paris and her motor trips to the Western front, collated at the end of 1915 into the volume Fighting France. She drew extensively on her experiences of these visits to the war zone when writing her war fiction. In addition to the afore-mentioned, Book of the Homeless, she published one of her best short stories, “Coming Home” in December 1915; two novels, Summer (1916) and The Marne (1918); and a travelogue on her official French government trip to North Africa undertaken in 1917 with General Lyautey, which appeared in 1920 under the title, In Morocco. Two further short stories on the war appeared in 1919: “The Refugees” and “Writing a War Story.” AND she began a full-length novel in 1918, A Son at the Front, which did not see publication until 1923 on account of Appleton, the original publisher, being unable to sell the serial rights because American readers had apparently tired of literature on the war. No wonder Henry James describes her in 1912 as an eagle swooping down on him “with a great flap of her iridescent wings” doing “4,000 separate & mutually inconsistent things” in the space of a ten-day visit (qtd in Lee, Edith Wharton 394). For an asthmatic, she left everyone else breathless. 4|Page An American Witness At the outbreak of the Great War, Wharton was 52 years old, recently divorced, and had just taken up permanent residence in France. She had first encountered France as a child when she accompanied her parents on extended visits to the Continent for financial and/or health reasons. She was well versed in the language and in French culture and history. Wharton was an early enthusiast for the motor-car1 and made three “motor-flights” through France in 1906 and 1907, by which time she owned a second-hand Panhard Levassor which Henry James dubbed “the Vehicle of Passion.”2 Wharton, the inveterate traveler, was in her element being driven by her faithful chauffeur, Charles Cook, and getting away from the dreaded “beaten track” (qtd in Dwight 120). In her 1908 travel book, A Motor Flight Through France, she waxes rapturously about the relationship between the French people and the land: Here in northern France . . . one understands the higher beauty of land developed, humanized, brought into relation to life and history, as compared with the raw material with which the greater part of our own hemisphere is still clothed. In France everything speaks of long familiar intercourse between the earth and its inhabitants; every field has a name, a history, a distinct place of its own in the village polity; every blade of grass is there by an old feudal right which has long since dispossessed the worthless aboriginal weed (5). This glimpse into how she wrote about France before the war gives us just a slight indication of how passionate Wharton was about her second country and helps us understand her stance in relation to the United States’ intervention in the Great War.3 1 The Whartons purchased their first car in 1904 (Dwight, Edith Wharton, An Extraordinary Life 120). 2 Teddy had it modified so that it was closed in and had an electric light fitted ; she and James called her cars “after characters in George Sand’s circle of lovers and friends” (Lee 224-27). 3 Lee refers to a fragment of a poem found in Wharton’s notebooks (454): 5|Page An American Witness She was an unofficial propagandist for the Allied cause and an outspoken critic of Woodrow Wilson’s neutrality policy. She told her close friend Gaillard Lapsley, a Rhode Islander, in December 1914 that it stuck in her “innards” that the United States was not “morally ready” to intervene (qtd in Price 35).4 The depth of her emotion and political fervor about the need to aid France is given expression in her novel, The Marne, in which the young male protagonist is a fervent supporter of France, itching to be old enough to enlist and deeply frustrated with America’s neutrality. Wharton ascribes to Troy Belknap feelings of passion about the importance of France to western civilization: Troy felt what a wonderful help it must be to have that long rich past in one’s blood. Every stone that France had carved, every song she had sung, every new idea she had struck out, every beauty she had created in her thousand fruitful years, was a tie between her and her children. These things were more glorious than her battles, for it was because of them that all civilization was bound up in her, and that nothing that concerned her could concern her only (TM 14). This short novel enjoyed initial success – one male reviewer went so far as to say it was “one of the very few clear-cut, pure-water, almost flawless gems of war fiction,” but it did not make it into the literary canon of war fiction (qtd in Olin-Ammentorp 89). In 1967 literary scholar, Stanley Cooperman, relegated Wharton to the ranks of women novelists who “seriously portrayed God-fearing boys blondly [sic] carrying the banners of Christian faith against a simian foe” (qtd in Price 173). Troy Belknap, too young to enlist, volunteers for the American Ambulance and finds himself caught up in the France! To give thee, o my more than country Give thee of my blood’s abundance all. 6|Page An American Witness Second Battle of the Marne. The ghost of his French tutor, who died at the first battle, saves Troy when he is shot in the back trying to rescue an injured soldier. And if this did not put off so many critics over the years, it would surely not have helped that Wharton included a reference to what Owen called “the old Lie,” “Dulce et decorum est,” in a scene where Troy thinks of his tutor’s death at the Marne and “the old hackneyed phrase . . . take[s] on a beauty that filled his eyes with tears” (ch.6). And, yes, Troy is a child “ardent for some desperate glory” (Owen, Dulce l.26). The Marne is the weakest of all her war-related fiction but its form is testimony to how a writer at the time grappled with and ordered her world, a world in chaos and one she experienced, like so many others, as a huge rupture. According to her biographer, Hermione Lee, Wharton’s “war writing was felt to be embarrassing and sentimental, an aberration from the sharp satire and bitter social dramas she was known for” (450). Recent critics have contended that there is still a satirical edge to her writing in the war pieces (Olin-Ammentorp, Price, Sensibar, Scutts), but in The Marne it is not a tone consistently held throughout the short novel. Wharton herself admitted to resorting to sentimentality when writing appeals to American readers for funds for her war charities. She told her sister-in-law that she had learned to put on a front that never blushes (qtd in Price 69). If that is what worked, then she was prepared to overcome her deeply-held prejudices about sentimental writing and construct “heartrending accounts … of individual cases … steeped in misery” (Price 4849). As The Marne was written after the United States had entered the war (and finished in the same month as the armistice), the reason for her use of sentimentality has perhaps rather less to do with appealing to Americans to support the war effort than with framing the war as one in which the United States had a rightful part to play 7|Page An American Witness in defense of western civilization: hence the honouring of those who died for their country. As alluded to earlier, we know from her correspondence that she believed from the outbreak of war that the United States should come to France’s defense. Responding to tales about German atrocities in Belgium, she wrote her friend Robert Grant, a wealthy Bostonian lawyer, judge and writer, to spread the word in the United States “what it will mean to all | we Americans cherish | if England and France go under, and Prussianism becomes the law of life” (31 August 1914, qtd in Lee 455). She sent a similar message a couple of days later to another Bostonian friend, Sara Norton, to spread the news about German atrocities, adding: It should be known that it is to America’s interest to help stem this hideous flood of savagery by opinion if it may not be by action. No civilized race can remain neutral in feeling now (Lewis and Lewis, eds., Letters 335). She shared the outrage of friends Henry James and former President Teddy Roosevelt at Woodrow Wilson’s insistence on neutrality and reneging on what they saw as the United States “international responsibilities” (Roosevelt’s words, qtd in Lee 459). In her public writings, Wharton was at pains to do all she could to urge American intervention. On the day the United States declared war on Germany, 6 April 1917, an article of Wharton’s (entitled “In The Land of Death”) appeared in the New York Sun in which she described a trip to northern France recently evacuated by the Germans. She decried the “systematic” and “vindictive” devastation wrought by the retreating army who did not confine their acts of destruction to roads and bridges. She accused them of “a deliberately planned attempt to murder the land as well as the people,” detailing the “slaughtering” of orchards and a massacre of women and children. She finishes with: 8|Page An American Witness It is impossible for any Christian nation not to be at war with Germany. With such a record as is spread here it is inevitable that whosoever is not with her is against her (reprinted in Olin-Ammentorp 257-61). Clearly, there is no sentimentality here but rather a classic example of dualistic thinking that reminds us of George W Bush in the aftermath of 9/11. There is no doubt whatsoever that Wharton demonized the enemy. In her private correspondence the Germans became “the Monster” or a “mad Gorilla” or “the Boche” or “the Beast.”5 As Lee points out, there is a slight modification in her fiction where they become “brutes and devils” (455). Wharton was militant in her patriotism towards France and wielded her pen in its defense. She honoured and praised those who fought for the Allied Powers and castigated pacifists and those who adopted a neutral position. Much as she was out of sympathy with her own country and some of its people, she could still make an appeal to its founding principles in a poem called “The Great Blue Tent” (1915) in which she hopes the Stars and Stripes can become the flag of freedom once more. And she could also feel shame at its neutrality and pride when it finally intervened in the war. She detested complacency and savagely satirized “fluffy” Americans in her fiction. Meanwhile she had a huge depth of sympathy for those whose lives and families were shattered by the war. She was highly practical in identifying the needs of unemployed work-girls, refugees and sufferers from TB (another of her war charities), and devoted herself to organizing viable charities to tend to those needs. She was exhilarated by the intensity of life in war-time Paris but also worn down by the 5 “the Monster only 80 miles away,” Edith Wharton to Robert Grant, 8 April 1915, qtd in Price 49; Edith Wharton to Bernard Berenson, 15 April 1917 qtd in Price 115: The horrors are unimaginable. Just one long senseless slaughters of the country . . . . Most of what we saw was just mad Gorilla-work. 9|Page An American Witness demands made upon her – so much so that she suffered a series of heart attacks in 1917 and 1918. For someone who felt things so keenly, it is perhaps not surprising that she ran through a gamut of emotions and struck so many different registers in her writing. If her war writings are seen as aberrational, perhaps there’s a very good reason for this. The violence of war is aberrational. And the ability to express oneself is challenged, as James once famously said in an interview with the New York Times: The war has used up words; they have weakened, they have deteriorated like motorcar tires; they have, like millions of other things, been more overstrained and knocked about the voided of the happy semblance during the last six months than in all of the long ages before, and we are now confronted with a depreciation of all our terms, or, otherwise speaking, with a loss of expression through an increase of limpness that may well make us wonder what ghosts will be left to walk.6 In her novel A Son at the Front, Wharton indicates a similar feeling through one of her characters who stumbles over his reference to the word “honourable”: “I was considering how the meaning had evaporated out of lots of our old words, as if the general smash-up had broken their stoppers. So many of them, you see, . . . we’d taken good care not to uncork for centuries” (101). In the last 25 years, Wharton’s war works have been reassessed as texts that document the Great War from her particular vantage point as a celebrated author, an American expatriate, a well-connected woman of means as well as a female noncombatant. The dismissal of her war fiction as slight, sentimental, bloodthirsty and 6 “Henry James’ First Interview: Noted Critic and Novelist breaks his rule of years to tell of the Good Work of the American Ambulance Corps,” New York Times Magazine, Sunday, March 21, 1915. 10 | P a g e An American Witness stridently nationalistic has been challenged as part of the general revision of the literary war canon and its marginalization of women authors and non-combatants. Wharton scholars have rethought the relationship of her war fiction to the rest of her considerable literary output and highlighted the continuities rather than the ruptures in her style and tone, as well as seeing the war years as a transformative period for her writing. Far from being a light comic piece, her 1919 short story, “Writing A War Story,” is now appreciated for its elements of parody and satire on men’s inability to see women as nothing but sexual objects. One could say that it has become the posterchild/-girl? for anthologies of women’s war writing. Fighting France, her account of her trips to the Front, has also undergone considerable reassessment and no longer dismissed out of hand as propaganda but appreciated for its illustration of tropes common to women’s articulation of and struggle with articulating scenes of destruction and ruin. From her very first publication—The Decoration of Houses (1897), coauthored with architect Ogden Codman—through to her novels on New York society and travel writings, Wharton strove to provide authoritative accounts and demonstrated her in-depth cultural knowledge. She combined this with her privileged access to the war zone accorded her by the French Red Cross and the French general staff. She proudly wrote James from Verdun in February 1915 that she had been greeted by officers and the Hospital with the declaration that she was the first woman to come to Verdun (Letters 350). Her friend and not always sympathetic biographer, Percy Lubbock, claimed that it was these trips to the Front which had opened up a “new field” for Wharton and work that was “entirely in accord with her mind and skill.” He goes on: She saw her chance at once, and made others see; she could here be used in the service of the cause for what she really war, a writer after all. With the best of effect, from this advanced position, she could face her large audience across the 11 | P a g e An American Witness ocean, where they waited and looked on; she could speak to them as an eyewitness of France in the fight. For so militant a neutral, and one to whom thousands were ready to listen, what fitter employment could be found? (Portrait 129-30) After what happened in Paris last month, I pondered what Wharton would have said and then I came across this sentence in a talk she gave to young American troops in Paris in April 1918: I believe if I were dead, and anybody asked me to come back and witness for France, I would get up out of my grave to do it (Price 150). 12 | P a g e An American Witness WORKS CITED Dwight, Eleanor. Edith Wharton, An Extraordinary Life: An Illustrated Biography. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994. Lee, Hermione. Edith Wharton. New York: Vintage, 2008. Lewis, R.W.B., and Nancy Lewis, eds. The Letters of Edith Wharton. New York: Collier Books, 1988. Lubbock, Percy. Portrait of Edith Wharton. New York: Appleton-Century, 1947. Olin-Ammentorp, Julie. Edith Wharton’s Writings from the Great War. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2004. Owen, Wilfred. The Poems of Wilfred Owen. Edited by Edmund Blunden. London: Chatto & Windus, 1969. Powers, Lyall H. Ed. Henry James and Edith Wharton: Letters: 1900-15. New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1990. Price, Alan. The End of the Age of Innocence: Edith Wharton and the First World War. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996. Scutts, Joanna. “’Writing a War Story: The Female Author and the Challenge of Witnessing.” Journal of the Short Story in English 58 (Spring 2012): 109-23. Sensibar, Judith L. “‘Behind the Lines’ in Edith Wharton’s A Son at the Front: Rewriting a Masculinist Tradition.” In Wretched Exotic: Essays on Edith Wharton in Europe. Edited by Katherine Joslin and Alan Price. New York: Peter Lang, 1993. Wharton, Edith. A Backward Glance. 1934; Wharton: Novellas and Other Writings. New York: Library of America, 1990. -------The Book of the Homeless. Edited by Edith Wharton. New York: Scribner’s, 1916. -------“Coming Home.” 1915. Collected Short Stories 2: 230-62. -------Fighting France. New York: Scribner’s, 1919. -------French Ways and Their Meanings. New York: Scribner’s, 1919. Lee, MA: Berkshire House, 1997. -------In Morocco. New York: Scribner’s, 1920. -------A Motor Flight Through France. 1908. -------Summer. New York: Scribner’s, 1917. -------A Son at the Front. New York: Scribner’s, 1923. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1995. -------The Marne. New York: Appleton, 1918. -------“The Refugees.” 1919. Collected Short Stories 2. New York: Library of America, 2001: 570-93. -------“Writing a War Story.” 1919. Collected Short Stories 2. New York: Library of America, 2001: 359-70. Wharton, Edith and Ogden Codman Jr. The Decoration of Houses. 1897.