12660634_HKU Conference - Tax Policy in NZ Aust 2015 revised Dec 2015.docx (194.7Kb)

advertisement

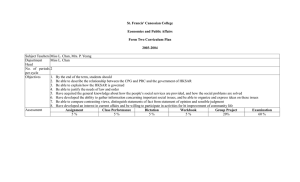

COMPARATIVE TAX POLICY APPROACHES IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA: INSTRUCTIONAL GUIDANCE FOR HONG KONG? Adrian Sawyer* Tax policy development in Australia and New Zealand has the hallmarks of consultation and input from various organizations outside of the government. Both countries operate as democracies, although Australia’s parliamentary system is more complex through the operation of both the Lower House and the Senate, and multiple layers of government that comes with a federal system. New Zealand has a unicameral House of Representatives, which facilitates the policy development process, notwithstanding operating under a Mixed Member Proportional system. In comparative terms, New Zealand’s tax policy process is more structured and transparent, highlighted by the Generic Tax Policy Process. Australia’s federal tax policy process operates with less cooperation between the Australian Treasury and the Australian Tax Office, compared to the New Zealand Treasury and Inland Revenue. In contrast, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) operates under the provisions of the Basic Law, with Articles 107 and 108 providing guidance with respect to tax policy development. This paper seeks to offer insights from Australia and New Zealand that could potentially inform the debate in the HKSAR over tax reform, especially with the HKSAR’s long term revenue planning, and recent proposals for more enhanced tax policy development. 1. Introduction There is perhaps no more stark contrast in the approach to developing tax policy within mature jurisdictions with respect to established tax regimes than that of New Zealand (NZ), and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). New Zealand, well recognized as an innovative (and perhaps radical) jurisdiction when it comes to taxation policy development, 1 has worked within the environment of the Generic Tax Policy Process (GTPP) since the mid-1990s following a review of the New Zealand Inland Revenue (NZIR). Australia, while not operating with such a *Professor of Taxation, Department of Accounting and Information Systems, College of Business and Law University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand. Ideas for this paper have been extensively drawn from prior work by the author; see in particular: Sawyer, A. “Establishing a Rigorous Framework for Tax Policy Development: Can New Zealand Offer Instructional Guidance for Hong Kong?”, Hong Kong Law Journal, Volume 43, Number 2, 2013, page 579. This paper states the position as at 30 September 2015. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Tax Law Research Programme, University of Hong Kong, Renovating the Hong Kong Revenue Regime: The Local, CrossBorder & International Contexts Conference, (31 October 2015). I wish to acknowledge the generous financial support provided by the TLRP in enabling me to attend and speak at this conference. The approach has been described as neo-liberal; for an analysis, see for example, Christensen, J. “Bringing the Bureaucrats Back in: Neo-liberal Tax Reform in New Zealand”, Journal of Public Policy, Volume 32, Number 2, 2012, page 141. 1 1 formalized process as the GTPP, utilizes consultation as part of the political and bureaucratic mechanisms that shape federal tax policy development. New Zealand’s tax base, especially following the work of various tax reform committees over the past decades, including the most recent Tax Working Group (TWG) in 2009–2010,2 is built upon a broad base low rate (BBLR) approach. BBLR in principle is a simple, understandable and coherent framework that is intended to lead to all areas of the economy being taxed reasonably consistently.3 As a result it generally reduces economic distortions and keeps administrative and compliance costs lower. However, practical realities necessitate that the most efficient revenue generating taxes are not applied, such as tailoring tax rates and the like to individual taxpayer’s circumstances. Thus while the most efficient tax would apply different rates depending on a taxpayer’s elasticity, this would be impossible to implement. BBLR also does not correct for positive and negative externalities in the economy generally. Furthermore, NZ currently does not tax all potential bases; for example, there is no capital gains tax (CGT),4 no financial transactions tax (FTT), no wealth taxes or land taxes. Overall, BBLR is seen as good as any other way of structuring a tax system that NZ has available, although it could be improved ‘around the edges’. It balances efficiency, fairness, compliance costs and administration costs, and has been endorsed by various tax reviews.5 Tax reform in NZ has been supported by “strong” governments over the years that have been willing to engage in consultation with the assistance of experts in various tax reform groups (in addition to government officials). This environment has continued notwithstanding a political structure that generally necessitates compromise through minority or coalition governments under a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system.6 Australia does not explicitly operate under the BBLR model, although the federal and state tax systems reflect the hallmarks of BBLR, through a broad base of taxes that extends beyond that of 2 The Tax Working Group (TWG) was established in 2009 under the auspices of Victoria University of Wellington following a seminar on tax reform held in early 2009. See further, The Centre for Accounting, Governance and Taxation Research, “VUW Tax Working Group”, http://www.victoria.ac.nz/sacl/cagtr/twg, October 9, 2015. This discussion on the BBLR is based upon a presentation by a senior NZIR official: Carrigan D., “Tax administration reform – retaining a coherent tax policy framework through change”, Tax Administration Conference (NZIR, June 2014). 3 4 Interestingly, in its 2013 Economic Survey of NZ, the OECD has recommended that NZ develop a comprehensive capital gains tax (CGT). The OECD states that the lack of a CGT in NZ exacerbates inequality (by reducing the redistributive power of taxation), reinforces a bias toward speculative housing investments and undermines housing affordability. 5 See for example, the McLeod, R. et al, Tax Review 2001, NZ Government, 2001; and Tax Working Group, op. cit. For further discussion on MMP, see Sawyer, A., “Reviewing Tax Policy Development in New Zealand: Lessons from a Delicate Balancing of ‘Law and Politics’”, Australian Tax Forum, Volume 28, Number 2, 2013, page 401, at page 408. See also Malone, R. Rebalancing the Constitution: The Challenge of Government Lawmaking under MMP, Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, 2008. 6 2 NZ. For example, Australia has a comprehensive CGT, and the States employ stamp duties on a range of real and personal property. Within the Australian GST, but unlike NZ which operates the most efficient GST in the world with an extremely broad base, the base remains narrow and the rate relatively low by comparison. 7 Like the TWG in NZ, Australia had a major review of its tax system, the Henry Tax Review (HTR).8 The Federal Government excluded GST from the terms of reference for the HTR, yet GST was the subject of a number of comments in the final report. In particular the final report specifically indicated that a narrower GST does not mean it is fairer, but it adds more complexity. Tax reform in Australia has been much more complex than NZ, which is largely due to the combination of both a Lower House and Senate in the Federal Parliament, and the interaction between the Federal Government and each of the States, exemplified by the inability, for example, to undertake any reform of the Australian GST. Indeed, work on the Abbott Government’s white paper on taxation, released earlier in 2015,9 was suspended as a result of the new Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull taking over in mid-September 2015. Tax policy is now to be developed ‘from the ground up” as a result of a “reset on tax policy”. 10 Thus, at the time of writing, it is not clear what direction Australia will take with respect to tax policy and reform, at least at the Federal level. In contrast to Australia and NZ, the HKSAR has a very narrow tax base, relying extensively on an income tax (levied predominantly on salaries and profits11), extensive land taxation, and a host of small (but collectively significant) indirect taxes (such as various duties on commodities, stamp duty and government fees). The debate over a GST during the period 2002–2007 reinforced acceptance that the HKSAR tax base is narrow with no consensus over what structural changes should be made (if any) to the existing tax base.12 For further discussion, see Sawyer, A., “VAT Reform in China: Can New Zealand’s Goods and Services Tax Provide Helpful Guidance?”, Journal of Chinese Tax and Policy, Volume 5, 2015, forthcoming; and Sawyer, A., “GST Reform: can New Zealand Offer Constructive Guidance to Inform the Australian Debate?”, Paper presented at QUT Business School, November 26, 2015. 7 Henry, K. et al, Australia’s Future Tax System: Report to the Treasurer, Commonwealth of Australia, 2010; http://taxreview.treasury.gov.au/content/Content.aspx?doc=html/pubs_reports.htm, October 9, 2015 (HTR). 8 9 Australian Federal Government, Rethink: Better Tax, http://bettertax.gov.au/publications/discussion-paper/, October 9, 2015. Better Australia, March 2015, See Hawthorne, M., “Malcolm Turnbull halts tax white paper in major ‘reset’” The Sydney Morning Herald, September 23, 2015. 10 11 Other items within the HKSAR tax base include: royalties, rents and property tax. For a discussion over the GST debate, see Sawyer, A., “New Zealand’s Successful Experience with Introducing GST: Informative Guidance for Hong Kong?”, Hong Kong Law Journal, Volume 43, Number 1, page 161. 12 3 The GST debate, including the background consultation document on tax reform released in 2006,13 reveals how relatively unsophisticated the tax policy development process is in the HKSAR compared to many other jurisdictions (including Australia and NZ). The GST debate also highlighted the lack of transparency and insufficient provision of extensive econometric analysis made available by government officials and independent experts to provide input to the tax policy debate. It is widely debated whether the HKSAR’s tax base needs widening, and assuming that it does, whether a GST would be the appropriate base broadening tool. Given this background then, how could the HKSAR improve its approach to tax policy development? One recent development has been the valuable work of the Working Group on Long-Term Fiscal Planning (WGLTFP), led by the Permanent Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau (FSTB), was set up in June 2013. 14 The WGLTFP, announced in the 2013-14 Budget Speech, is charged with exploring ways to make more comprehensive planning for the HKSAR’s public finances to cope with the ageing population and the HKSAR Government’s other long-term commitments. The WGLTFP comprises government officials and non-official members who are scholars and experts with vast experience and rich knowledge in their professions/sectors, such as economics, accountancy, financial services and actuary services. The objective of the WGLTFP is to assess, under existing policies, the long-term public expenditure needs and changes in government revenue, and to propose feasible measures with reference to overseas experience. The WGLTFP has completed a fiscal sustainability appraisal on the public finances in Hong Kong and released its report on 3 March 2014 (Phases 1 and 2). 15 In many ways, this has a similar membership to the TWG in NZ, although the TWG was established independently of the NZ Government. This paper seeks to be both challenging, and in a sense a little provocative, with its motivation being to offer perspectives from Australia and New Zealand for the HKSAR to investigate when charting a path forward with respect to tax policy reform, namely examining (and potentially adapting) the NZ GTPP. It also suggest that the HKSAR should embrace a more “independent” and structured approach to tax policy reform. It is not my intention in this paper to prescribe how Henry Tang (Financial Secretary), Broadening the Tax Base, Ensuring our Future Prosperity – What's the Best Option for Hong Kong?, HKSAR Government, 2006, http://www.taxreform.gov.hk/eng/doc_and_leaflet.htm; June 4, 2013. 13 14 See further: http://www.fstb.gov.hk/tb/en/working-group-on-longterm-fiscal-planning.htm. The WGLTFP has, as at the time of writing, released one report (Phase 1 and 2) which is available on its website. 15 See WGLTFP, Report of the Working Group on Long-Term Fiscal Planning, HKSAR Government, March 2014, http://www.fstb.gov.hk/tb/en/report-of-the-working-group-on-longterm-fiscal-planning.htm, 8 October 2015. In addition to the reports, multimedia resources are provided, including videos and games. This illustrates a novel approach to engage wider sectors of the population in the debate over fiscal reform. 4 the HKSAR should reform its current tax base. Indeed, the WGLTFP has made excellent progress in putting the wider fiscal future of the HKSAR in the spotlight. The challenge will be to develop policy reform options that can then be publicly debated. In essence the approach taken in this paper is both positivist and normative, in that the paper seeks to both outline the comparative tax reform processes of Australia and New Zealand (positivist), and to offer insights and suggestions for the HKSAR to debate further in its wider fiscal reform and tax base review debates (normative). It is also a critical realist approach in that as the author I am acutely aware of the political nature of tax policy debates (not only in both Australia and NZ, but also in the HKSAR), and that what may work in one jurisdiction may not in another, no matter how much adaptation is undertaken. As an outsider, rather than someone closely involved with the HKSAR’s political and business activities and negotiations, the suggestions made in this paper may be seen to be well intentioned but biased by the perspectives of someone based in the West.16 The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly outlines the policy development process in Australia including the HTR, with section 3 presenting the NZ GTPP, along with the contributions of the most recent review of the tax base in NZ, the TWG. Section 4 then briefly reviews the fiscal reform proposals in the HKSAR, with section 5 setting out the concluding observations and areas for future research. Lessons and potential insights for the HKSAR from the Australian and NZ approaches to tax policy development are also offered. 2. A Review of the Tax Policy Process in Australia and the Henry Tax Review In providing an overview of the tax policy process in Australia, one needs to digest two contrasting views as to the acceptability of the tax policy process, especially with regard to consultation. 2.1 Tax policy development in Australia Dirkis and Bondfield, 17 in their independent (academic) review of tax policy development in Australia, contrast the Australian approach with the GTPP in relation to consultation in tax policy 16 In a sense it can be an advantage to approach the issue of tax policy as an outsider, since one is freer to offer a critical realist’s perspective without the limitations of publicly commenting on matters of national importance associated with one’s occupation, particularly as a government official or someone closely aligned with the jurisdiction. Furthermore, I have been fortunate to spend several periods in the HKSAR, observing not only the manner in which the HKSAR Government (and more generally, the political environment) functions, but also immersed myself in the debates over the GST proposal and exchange of information reforms. Thus, I feel able to offer a perspective that warrants serious consideration within the HKSAR if it wishes to advance the debate over its revenue regime. Dirkis, M. and Bondfield, B., “At the Extremes of a “Good Tax Policy Process”: A Case Study Contrasting the Role Accorded to Consultation in Tax Policy Development in Australia and New Zealand”, New Zealand Journal of Taxation Law and Policy, Volume 11, Number 2, 2011, page 250. 17 5 development, making a number of pertinent observations. The authors focus on differences of tax policy significance between Australia’s and NZ’s systems of government (the former being a two house parliamentary system and the latter a one house MMP-style parliamentary system). Dirkis and Bondfield observe that external consultation is not as important in the Australian process compared to NZ. They also assess whether the NZ GTPP’s rhetoric is matched by reality, concluding that the evidence is somewhat mixed.18 Further analysis of NZ’s GTPP is included in the next section of the paper. Turning to the approach in Australia, up to 1 July 2002 (in theory at least), the Tax Policy Division of the Australian Treasury (Australian Treasury) had the responsibility for policy, the Office of Parliamentary Counsel (OPC)) the responsibility for drafting legislation (with subordinate legislation (regulations) being drafted in the OLD), and the Australian Tax Office (ATO) the responsibility for implementation and administration. In 2000, the Board of Taxation (BOT) was charged with the responsibility of overseeing consultation in respect of tax reform measures. 19 In 2002, the Treasurer accepted the BOT’s recommendation to create a Tax Policy and Legislative Unit (TPLU), consisting of ATO and Australian Treasury staff, to be located within the Australian Treasury. However, the OPC would remain separate, retaining responsibility for the drafting of tax legislation, as a service provider to the TPLU. Dirkis and Bondfield observe that by leaving OPC outside the equation, accountability for poorly drafted law remains elusive. 20 Importantly, the BOT is charged with monitoring the consultation process. In contrast to Dirkis and Bondfield, Heferen et al. are much more upbeat about tax policy formulation in Australia.21 The authors all work for the Australian Treasury, the major ‘player’ in tax policy development in Australia, and from this perspective, the views expressed could be seen as less independent and not able to be critical of the process. Essentially there are three stages: Development, Legislative and Post Implementation Review, although these are not as formalized as set out in the NZ GTPP. The authors review the roles of the major government departments with a role in tax policy formulation (Australian Treasury and the ATO). Issues of resource allocation and 18 ibid., pages 274-275. 19 The Board of Taxation is a non-statutory advisory board, which was established on 10 August 2000 to advise the Government (Treasurer) on the development and implementation of taxation legislation, as well as the ongoing operation of the tax system; see Costello, P., “The New Business Tax System”, Press Release 58, September 21, 1999; and Costello, P., “Board of Taxation: Membership”, Press Release 83, August 10, 2000. 20 Dirkis and Bondfield, op. cit., page 260. Heferen, R., Mitchell N., and Amalo, I., “Tax Policy Formulation in Australia”, Canadian Tax Journal/Revue Fiscale Canadienne, Volume 61, Number 4, 2013, page 1011. This article is part of a special feature on tax policy development that also included contributions from Canada, NZ, United Kingdom and the United States. 21 6 consultation are discussed, suggesting that since 2000, consultation has become more widespread and has been regularized. The roles of other governance bodies, especially the parliamentary Budget Office, are briefly discussed. In this regard, Table 3 in their article indicates the sizeable number of tax governance bodies (ten in total), which highlights the relative complexity and blurring of boundaries and accountabilities that are imbedded in the Australian tax policy process. 22 Cooper’s additional comments to this article provide, in my view, a more balanced and critical perspective, indicating that most consultation is ex post. Cooper states:23 “However, while there is a lot of consultation, it almost always occurs ex post: day-to-day tax policy proposals almost always emerge from government as a fait accompli without the benefit of any transparent, prior, and external involvement. Instead of being involved in policy development, the participation of actors external to government is typically limited to policy refinement and issues of implementation. The one exception is policy announcements that have been prompted by lobbying, but that too is not conducted in public.” This approach to ‘consultation’ leads to mistakes and errors that would not have been made had there been earlier public consultation. More significant tax proposals, however, are usually ‘road tested’ before implementation. Cooper highlights the tensions between the Australian Treasury and ATO in tax policy development and implementation, a situation that existed in NZ before the GTPP was implemented. With respect to consultation, different models are utilized in practice, which is not necessarily desirable, nor does it lead to the most effective outcome. Arnold, in commenting on the papers presented at the roundtable session hosted by the Canadian Tax Foundation, observes:24 “The extent of consultation is both a strength and a weakness of the Australian tax policy process. Its strength lies in the access that consultation provides to the views of the public, especially tax professionals. Its weaknesses are twofold: first, the private sector is experiencing “consultation fatigue” as a result of the need to participate in so many consultation exercises; and second, consultation sometimes produces mixed responses, with no clear direction for the government.” 22 ibid., page 1022. Cooper, G., “Some Additional Comments on Australia’s Tax Policy Process”, Canadian Tax Journal/Revue Fiscale Canadienne, Volume 61, Number 4, 2013, page 1023 (emphasis added). 23 Arnold, B., “The Process of Making Tax Policy: Summary of Proceedings”, Canadian Tax Journal/Revue Fiscale Canadienne, Volume 61, Number 4, 2013, page 989, at page 993 (emphasis added). 24 7 The BOT’s role is seen as positive feature of the Australian system, although Arnold highlights the tension between the Australian Treasury and the ATO with respect to tax policy. Arnold also observes that Australia carries out fundamental reviews of its tax system more frequently than other countries. The current author has experienced first-hand the ‘tensions’ and mixed views concerning how the Australian tax policy and wider regulatory process could be made more transparent and utilize wider consultation. Following a number of presentations by the author in April 2014, 25 it was abundantly clear that while many officials working for bodies such as the Office of the Small Business Commissioner (OSBC), the ATO and the Australian Treasury, were receptive to greater consultation and transparency (as featured in the NZ GTPP), the obstacles in place to any real movement in this direction was perceived to be the politicians. 2.2 The Henry Tax Review Before reviewing the impact of the HTR, it is useful to first ask the question: “However, how can we measure whether tax reform is successful?” Sandford suggests that, based on tax reform in six countries, there are three criteria by which successful tax reform may be judged: 26 the extent to which the tax reforms met the objectives the reformers set themselves; the sustainability of the reforms; and the extent to which the tax reforms had desirable or undesirable by-products. Evans suggests that the prospects of tax reform being successful will be enhanced with the following factors:27 The existence of a ‘vision’; Sound economic principles; The political dimension; Sawyer, A., “A Review of (Tax) Policy Development in New Zealand: A Conversation”, Presentation to the ASBC, ATO and Australian Treasury (April 2014). 25 26 Sandford, C., Successful Tax Reform: Lessons from an Analysis of Tax Reform of Six Countries, Fiscal Publications, 1993, page 5. Evans, C., “Reviewing the Reviews: A Comparison of Recent Tax Reviews in Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand or ‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”, Journal of Australian Taxation, Volume 14, Number 2, 2014, page 146, at pages 175-180. 27 8 A political champion; Constitutional and other factors; A package of reforms; and An appetite for reform. In May 2008, the Commonwealth Government of Australia announced the scope of a major review into Australia’s Future Tax System, chaired by the Secretary to the Australian Treasury, Dr Ken Henry (referred to as the HTR). The HTR was undertaken in an environment that featured high personal income tax marginal tax rates, high social welfare effective marginal tax rates, high taxes on capital, as well as high complexity and compliance costs. Almost all taxes were to be reviewed along with all transfers and issues such as superannuation. While State taxation was included, unfortunately GST was excluded. GST comprises a sizeable component of the Australian tax base which has been the subject of considerable debate but is lacking in fundamental reform. The aim of the HTR was to “create a tax structure that will position Australia to deal with its social, economic and environmental challenges and enhance economic, social and environmental wellbeing”. 28 The HTR developed nine themes, leading to 138 detailed recommendations. evaluation criteria for evaluating the Australian tax system in the HTR are set out below: 28 Henry, op. cit., at page v. 9 The Figure 1: Tax Design Principles29 Overall, the HTR has been seen as being moderately successful in reviewing taxation policy in Australia and offering a number of recommendations for reform. While a number of the recommendations were adopted, most have not been taken up by successive governments, in part due to political infighting within the governments. Furthermore, many of Evans’30 suggested key features for successful tax reform have not been present, such as the lack of a political champion, the complex constitutional issues (including the restrictions placed on the HTR's terms of reference), and perhaps an overall a lack of an appetite for major tax reform. Such cannot be said for NZ as will be discussed in the next section of the paper. 3. A Review of the Generic Tax Policy Process and the Role of the Tax Working Group in New Zealand In this section of the paper, the author seeks to provide a summary of the experience of the GTPP in NZ, along with the approach and impact that the TWG had in contributing to tax reform in NZ in the last six years. Thus in this section of the paper the GTPP is outlined, with a brief explanation of how it operates, and a comment on its utilization and influence on tax policy development. This is See Warren, N., “Policy Forum: The Henry Review of Taxation: The Henry Review, State Taxation and the Federation”, The Australian Economic Review, Volume 43, Number 4, 2010, page 409, at page 410. 29 30 See Evans, op. cit. 10 followed by a review of the TWG’s contributions as a model of independent analysis and advice to the NZ Government, buttressed by an environment based on transparency and open consultation. 3.1 The Generic Tax Policy Process As commented elsewhere,31 NZ chose to take a new and innovative route in the mid-1990s with the adoption of the GTPP, a blueprint for formulating tax policy. The GTPP emerged as a bi-product of a review of the New Zealand Inland Revenue (NZIR) conducted through a committee (known as the Organizational Review of Inland Revenue) chaired by Rt. Hon. Sir Ivor Richardson, former President of the New Zealand Court of Appeal. 32 Sir Ivor Richardson identified a number of problems with the previous process for developing tax policy, noting that:33 “ the subject matter is complex, and tax legislation is very complex and difficult to understand. The tax policy process was not clear, neither were the accountabilities for each stage of the process. There was insufficient external consultation in the process.” A Cabinet directive implemented the GTPP during the review process as a form of administrative or customary practice, rather than formally by way of legislation or regulation. This approach in part, as argued elsewhere, reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of the GTPP.34 The GTPP’s approach to tax policy development and reform is in complete contrast to the previous policy environment, which was characterized by an absence of clarity and ascertainable accountabilities during each stage of the process. The process was largely controlled by the Minister of Finance and key officials, with the perception was that the external consultation was insufficient to the extent of being virtually ineffective.35 With the GTPP, the NZ Government and policy officials are able to draw upon the technical and practical expertise of the business community and to factor in compliance and administrative effects of potential policy changes. Furthermore, the GTPP provides a mechanism to communicate the rationale for policy changes which assist with educating taxpayers about the need for the change 31 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 6). 32 Richardson, Rt. Hon. Sir I., Organisational Review of the Inland Revenue Department, Report to the Minister of Revenue and the Minister of Finance, Inland Revenue, April 1994. Sir Ivor Richardson was also instrumental in his oversight of the Rewrite Advisory Panel that worked alongside the NZ Government’s fourteen year project to rewrite the Income Tax Act; for an analysis see Sawyer, A., “RAP(ping) in Taxation: A Review of New Zealand’s Rewrite Advisory Panel and its Potential for Adaptation to Other Jurisdictions”, Australian Tax Review, Volume 37, Number 3, 2008, page 148. 33 See Richardson, ibid., page 5. 34 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 6), page 403. 35 ibid., page 403. 11 and its implications. The GTPP, upon first review, may appear to be complex and potentially unwieldy, but with further examination, it provides a comprehensive and robust structure for the development, refinement and enactment of tax policy into legislation.36 The GTPP has five core stages, each of which has their own components totalling 16 phases (see Figure 2). The subject matter of reform is almost always firmly rooted in the government of the time’s economic, fiscal and revenue strategies (Phases 1–3). A further feature of the GTPP is the requirement for the NZ Government to announce annually its Rolling Three Year Work Programme (RTYWP)37 which in turn leads to the annual work and resource plan of the NZIR. The GTPP contains a number of external inputs and feedback loops, including a post implementation of legislation review. Throughout the GTPP, the linkages and feedback loops are intended to reflect a flexible process that recognizes that some activities may occur simultaneously or in a slightly modified order, such when legislative drafting may occur (within Phases 6–12). Phases 9-14 are part of the Parliamentary process and were in place long before the GTPP was developed. For an in-depth early discussion of the various stages of the GTPP, see Sawyer, A., “Broadening the Scope of Consultation and Strategic Focus in Tax Policy Formulation: Some Recent Developments”, New Zealand Journal of Taxation Law and Policy, Volume 2, Number 1, 1996, page 17. 36 The latest RTYWP is available at the NZIRD’s http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/work-programme, October 8, 2015. 37 12 Policy Advice Division’s website at: Figure 2: The Generic Tax Policy Process (Organisational Review Committee, 1994) Phases Strategic (1-3) Output from phases 1-3 widely publicised by Government – possibly through Budget documentation 1. Economic Strategy* 2. Fiscal Strategy* Reconciliation with other Government Objectives 3. Three Year Tax Revenue Strategy* Tactical (4-5) Phases 3-5 are linked with the Budget process and have a high degree of simultaneity 4. Rolling Three Year Work Programme* 5. Annual Work and Resource Plan* 6. Detailed Policy Design* Operational (6-8) 7. Formal Detailed Consultation and Communication 8. Ministerial and Cabinet Sign-off of Policy* 9. Legislative Drafting (phases 6-12) 10. Ministerial and Cabinet Sign-off of Legislation* EXTERNAL INPUT External input, as appropriate, through Green paper (ideas) stage and/or through White paper (detail) stage by: 1. Secondment of personnel from private sector; 2. A permanent advisory panel; 3. Issues based Consultative Committees; or 4. Submissions on Consultative Document Issues encountered at later stages of the process, and decisions taken to change policy, may lead to reconsideration of earlier phases. Legislative (9-13) 11. Introduction of Bill 12. Select Committee Phase 13. Passage of Legislation 14. Implementation of Legislation Implementation and Review (14-16) 15. Post Implementation Review 16. Identification of Remedial Issues *Cabinet Decision 13 Consultative Committee may be required to explain the intent of their recommendatio ns to Select Committee The NZ Government was encouraged to adopt the GTPP as a result of three key features it possesses. 38 First, the GTPP clarifies the responsibilities and accountabilities of the two major departments actively involved in the process, namely the NZIR and the New Zealand Treasury (NZ Treasury). Second, the GTPP encourages earlier and more explicit consideration of key tax policy elements and trade-offs through linking the first three stages. Finally, the GTPP provides an opportunity for external input (such as from practitioners) into the process for formulating tax policy to increase both the actual and perceived transparency of the process, and provide for greater contestability and quality of policy advice. This external input can be initiated by non- governmental bodies, as was the case with the TWG. An important weakness in the GTPP is that late policy or legislative developments may be added by way of a Supplementary Order Paper (SOP) 39 during the parliamentary phase, and as a consequence, such policy is not exposed to public scrutiny via formal consultation. While this is not a problem where the change is remedial and corrective of minor defects in existing legislation,40 if significant new developments are introduced, this is a major concern. Such actions effectively bypass the GTPP, leading to lower quality legislation (technical content and drafting).41 So why has the GTPP managed to survive? Sawyer42 reviewed the prior literature on the GTPP and examines why it has been successful and managed to survive the highly political policy environment that operates in NZ. One important element has been its adaptability to change to the various manifestations of political policy development in NZ, along with the electoral system, and a general acceptance of its merits from politicians across the spectrum. Furthermore, the private sector has continued to operate in a cooperative manner with officials. When the MMP political system commenced shortly after adoption of the GTPP, this was expected to provide a challenge to the operation of the GTPP. 43 When the GTPP was introduced, NZ had a 38 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 6), page 404. 39 An SOP is a late legislative amendment introduced by the Government at the Second Reading stage (during Step 13 in the GTPP) after the Select Committee has reported on the Bill (that is, after the consultation process has been completed). Usually these will be remedial and minor in nature, but this is not always the case. Step 13 in reality involves several steps, as shown in Figure 2. 40 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 6), page 404. See the comments of Vial, P., “The Generic Tax Policy Process: A “Jewel in Our Policy Formation Crown”?”, New Zealand Universities Law Review, Volume 25, Number 2, 2012, 318–346. 41 42 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 6), pages 404–425. 43 A feature of the MMP system has been (minority) coalition governments, with the major party needing to work closely with several other smaller parties to develop tax policy. 14 First Past the Post (FPP) 44 election system for its single house Parliament (the House of Representatives). The evidence post the introduction of MMP indicates that it has not prevented major tax reform in NZ, with the TWG in 2009-2010 complementing the contributions of the GTPP to tax policy development in NZ with the most significant tax reform in 25 years. It is important to recognise that the BBLR approach to tax policy was established prior to the GTPP, and apart from the work of the TWG, the GTPP has not been tested in an environment of fundamental tax policy change. In a sense the GTPP has facilitated what could be considered at most to be significant renovation of NZ’s tax system (and associated policy). Outside of taxation, the GTPP formed the basis for a much wider form of policy development, the Generic Policy Development Process (GPDP), implemented from 2005.45 Reference to, and apparent use of, the GPDP ceased several year’s ago. Outside of NZ, how has the GTPP been perceived? Dirkis and Bondfield 46 argue that the GTPP is “as good as it gets” in the tax policy arena, given the resources that NZ has available to it. They also suggest that there is much for other countries, including Australia, to learn and adapt from NZ’s GTPP experience. The authors conclude:47 “The standard of New Zealand openness is exemplified by Inland Revenue posting its briefing to the incoming Minister; in Australia, these are more likely to find themselves on a quick trip to the shredder rather than the web. In this regard, Australia still awaits the release of a report on an assessment of world best practice consultative tax policy practices commissioned by the Board of Taxation.” Little et al, as part of the Canadian tax policy forum, offer insights into the GTPP from both NZIR and practitioner perspectives. 48 The authors highlight the large degree of cooperation and trust between the private and public sectors in NZ where the view is to consider what is best for ‘New Zealand Inc.” (or NZ as a whole). This includes private sector practitioners on occasions 44 FFP is a system whereby the person who receives the highest number of votes for their electorate seat will win that seat. The party with the highest number of electorate seats will then be asked to form a government. If that party has more than 50 per cent of the electorate seats then it can become the government without needing to form a collation with one or more additional parties. Usually a government would be formed by a single political party that held a majority of electoral seats. 45 Ministry of Economic Development, Origin and Objectives of the GPDP (12 December 2005); available from http://www.med.govt.nz. 46 Dirkis and Bondfield, op. cit. 47 ibid., page 275 (emphasis added). Little, S., Nightingale, G.D., and Fenwick, A., “Development of Tax Policy in New Zealand: The Generic Tax Policy Process”, Canadian Tax Journal/Revue Fiscale Canadienne, Volume 61, Number 4, 2013, page 1043. The authors come from the NZ Treasury and a Big 4 Accounting firm. 48 15 advocating for changes that are not in their own direct financial interests. 49 The authors discuss the important role of the major private sector organizations that are involved in the consultation process, highlighting that they often initiate policy changes and suggest modifications to proposals to facilitate their effective operation. 50 Little et al acknowledge that the potential for transportability of the GTPP depends in part on the size of the economy of a country, the underlying policy paradigm, and broad tax policy framework (such as BBLR in NZ). Arnold, in his overview of the papers presented at the policy forum, offers the following overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the NZ GTPP:51 “The strengths of the New Zealand process for making tax policy are: the participation of private-sector tax professionals in the process on both a formal and an informal basis; the open access to Inland Revenue tax policy officials and the minister accorded to tax professionals; the shared responsibility for tax policy and cooperation between the Treasury and Inland Revenue; the integration of the broad policy, legislative design, and drafting functions, coupled with a tight legislative process, which results in a tax policy process that is fast and certain; and the publication each year by Inland Revenue of its work program for the next 18 months, so that the public is notified on an ongoing basis of the tax issues that the government considers to be important. The weaknesses of the New Zealand process are the following: The resources devoted to tax policy are shrinking at a time when demands on tax policy officials are increasing; as a result, insufficient strategic thinking occurs with respect to tax policy and fewer foreign consultants are used; There is insufficient post-implementation review of tax measures; 49 ibid., page 1050. 50 ibid, 1051. 51 Arnold, op. cit., page 996. 16 Consultation on proposed tax measures limited to the New Zealand tax community is increasingly inadequate in a global economy.” In a similar vein to Dirkis and Bondfield, Arnold also comments favourably on NZIR’s (and NZ Treasury’s) approach of providing tax policy advice for newly elected governments which then becomes a public document once the responsible ministers have had sufficient time to consider the advice.52 Arnold concludes that:53 “New Zealand’s situation is so special in many respects (and not just because of the country’s small population) that its GTPP is not readily transferable to other countries. Nevertheless, it was suggested that it would be worthwhile to develop model or best practices with respect to the institutionalization of the relationships among the principal players in the tax policy process.” Little et al conclude favourably on the GTPP, concluding:54 “Tax policy works fairly well in New Zealand. An important reason is the formalized GTPP process, which encourages consultation early and often in the development of tax policy. However, a good tax policy process goes beyond formalized consultation. For the GTPP to work well, there need to be coherent policy settings that the private sector can buy into. Moreover, a good tax policy process is not something that can be captured in a written roadmap. It requires willingness between the government, officials, and the private sector to truly listen and engage. It is critical that the government be open to acting on good suggestions put forward by the private sector.” 3.2 The Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group Sawyer observed55 that in 2009, following a conference held at Victoria University of Wellington (VUW), that it was decided to establish an independent group (known as the TWG) comprising experts from academia, NZIR, NZ Treasury and tax practice, to undertake a review of the NZ tax 52 ibid., 1006. 53 ibid., 1007 (emphasis added). 54 Little et al, op. cit., page 1056 (emphasis added). See Sawyer, A., “Moving on from the Tax Legislation Rewrite Projects: A Comparison of New Zealand Tax Working Group/Generic Tax Policy Process and the United Kingdom Office of Tax Simplification”, British Tax Review, Number 3, 2013, page 321. 55 17 system from a core principles policy focused perspective. 56 The TWG, being established independently of the NZ government with its own terms of reference, differed from earlier reviews of the tax system in NZ, such as the Tax Review 2001.57 Furthermore, while the TWG received resource support from the NZIR and the NZ Treasury, it operated separately from and outside the “government appointed committee” framework of earlier reviews.58 Thus while the TWG is not a necessity for an effective GTPP, the evidence clearly indicates that it facilitated the development of higher quality policy and legislation through its input into the GTPP.59 The TWG displays the hallmarks of transparency and consultation, providing an extensive report to the NZ government, which resulted in a series of recommended options for major tax policy reform.60 The TWG sought to:61 1. identify concerns with the current taxation system; 2. describe what a good tax system should be like; 3. consider options for reform; and 4. evaluate the pros and cons of these options. In its 2010 Report, the TWG concluded that NZ’s tax system faced three critical issues:62 (1) its structure was inappropriate; (2) it lacked coherence, integrity and fairness; and 56 Details of independent, Inland Revenue and Treasury members of the TWG can be found at, The Centre for Accounting, Governance and Taxation Research, op. cit. Details of the number of experts who assisted the TWG are also provided. 57 The Tax Review 2001 (also known as the McLeod Review) was established by the NZ Government in 2001 to carry out a public review into the tax system. The functions of the Tax Review 2001 were to: examine and inquire into the structure and effects of the tax system in NZ; to formulate proposals for improving that system, either by way of making changes to the system, abolishing any existing form of tax, or introducing new forms of tax; and to report to the NZ Parliament through the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Revenue and the Minister of Economic Development. The terms of reference were set within the constraints of maintaining revenue neutrality with any recommendations for change; available at http://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/reviews-consultation/taxreview2001, (October 8, 2015). 58 These operate within the External Input phase of the GTPP. 59 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 55), page 323. Tax Working Group, A Tax System for New Zealand’s Future Report of the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group, Centre for Accounting, Governance and Taxation Research, Victoria University of Wellington, January 2010, (A Tax System for New Zealand’s Future). 60 61 ibid., page 19. For further details, see http://www.victoria.ac.nz/sacl/cagtr/twg/report.,(October 8, 2015). 62 ibid. 18 The TWG’s Report available at, (3) significant risks to the sustainability of the tax revenue base existed. Consequently, the TWG established six principles for reform,63 and made a number of significant recommendations for reform, including major changes to tax rates, structures and bases. 64 The TWG referred its recommendations, which included a series of options or combinations of structural tax reforms, to the NZ Government for its consideration.65 In the 2010 Budget the NZ Government announced a major overhaul of the NZ tax system, adopting many of the recommendations of the TWG.66 Prior analysis has reviewed the comments on the contributions of the TWG within the GTPP environment, from those involved either as members of the GTPP (including the Chair, Professor Bob Buckle), advisors (Norman Gemmell) and expert consultants (Professor John Creedy). As Sawyer notes, 67 collectively these commentators/academics emphasize the importance of the interdisciplinary backgrounds and expertise of those involved, the attempt to rationalize tax policy debate, and engaging the public in the debate. A major constraining factor with most reviews, the TWG being no exception, is the revenue neutral constraint placed on reviews (something that was also present in the HKSAR GST debate). Focusing on addressing issues of fairness, especially horizontal equity, was also crucial to the TWG’s success. Previous instances of review of the NZ tax system, such as the Tax Review 2001, 68 involved government-appointed bodies that had reporting obligations to the NZ Government, and as such, were part of the external consultation process in the GTPP. At the time of the Tax Review 2001, it was established by a left of centre government, which also set the terms of reference and rejected most of the recommendations. 69 With the TWG, it was a “right of centre” government, receptive to reform, that permitted the TWG to sets its own terms of reference and accepted many of its recommendations. The GTPP has continued to operate largely unscathed under both left-wing and right-wing governments. 63 The six principles are: the overall coherence of the system; efficiency and growth; equity and fairness; revenue integrity; fiscal cost; and compliance and administration costs. 64 For a summary, see Tax Working Group, op. cit., pages 10–11. 65 The recommendations were included in the TWG’s January 2010 report that was publicly available; ibid. 66 For details of the New Zealand Budget 2010 announcements, see: http://www.treasury.govt.nz/budget/2010. June 13, 2013. 67 See Sawyer, op. cit. (note 55), pages 322–327. 68 See Tax Review 2001, op. cit. 69 Interestingly, the Tax Review 2001 comprised a mix of right-wing and left-wing members. 19 Little et al70 argue that the TWG proved to be a considerable success, being an open forum for debate, with papers provided from meetings, debates published, and all reasonable steps taken to inform the wider public of the key tax policy issues. The media is also seen as playing a key role in tax policy matters in NZ, assisting with ensuring the BBLR framework has not been departed from.71 This open approach also worked well from the NZ Government’s perspective, with the author’s observing:72 “It allowed possible tax changes to be aired publicly and debated openly, and it brought the academic community into important tax policy debates. However, a large element in its success was the cooperation and engagement of key tax practitioners. This was built on the engagement and cooperation that had been built up through many years of working with the GTPP.” Overall this paper has sought to argue that the GTPP, (even without the contribution of the TWG), is genuinely world-class, illustrating how politics can be separated from much of the tax reform process. In that regard the GTPP offers an alternative approach from which other jurisdictions, such as the HKSAR, may be inclined to learn. The paper now turns to focus on recent tax reform in the HKSAR. 4. Tax Policy Development and Reform in the HKSAR – Recent Developments It is not my intention to rehearse the tax policy approach and history of the HKSAR in this paper. For those that are interested they can refer to my earlier work in 2013, 73 or that of other leading scholars, such as Cullen and Wong, 74 and Littlewood. 75 The HKSAR’s tax system (revenue regime) has a narrow base, is relatively simple, and relies heavily on revenues from land. In this regards Cullen states: 76 70 See Little et al, op. cit., page 1052. 71 ibid., 1053. 72 ibid., 1053 (emphasis added). 73 See Sawyer, op. cit., (note 6). 74 Cullen, R., and Wong, A., Foundations of the Hong Kong Revenue Regime, Civic Exchange, 2011. Littlewood, M. Taxation Without Representation: The History of Hong Kong’s Troublingly Successful Tax System, Hong Kong University Press, 2010. 75 Cullen, R., “Far East Tax Policy Lessons: Good and Bad Stories from Hong Kong”, Paper presented in conference in honour of Professor Neil Brooks, Toronto, April 2013. 76 20 “I believe there are two primary (interlocked) positive lessons to be drawn from the Hong Kong Revenue Policy experience. The paramount, evolved-innovative, policy idea is the continuing use of land, to this day, as a fundamental public revenue source This is the second key positive lesson that Hong Kong offers: it is possible to maintain, in the modern era, a highly effective revenue regime that is minimalist, clear and easy to comply with – where you have been able to retain a significant, land-based, revenue source The success of this evolved-innovation also underpins the primary, bad aspects of the HKSAR RR, however. Again, two stand out. Broadly stated, these are notable revenue policy inflexibility and the high on-cost effects of the land-based, revenue system.” A notable feature of the HKSAR legislative process is the absence of any formal mechanism for including consultative documents or the setting up of review panels for reform of legislation in the HKSAR. Nevertheless, the HKSAR Government could choose to employ various consultative measures, such as advisory committees or task forces, which will be charged with providing some form of consultative report. Indeed, the HKSAR Government has previously set up advisory bodies with a minority of civil servants as members. Notwithstanding its defeat over the GST proposal,77 the HKSAR Government has continued to study options for creating a more stable revenue base. Scott identifies one approach that may be taken is for the HKSAR Government to charge for services that it currently offer at highly subsidized rates as well as greater personal contributions to assist with funding healthcare.78 As noted by Sawyer,79 when proposing amendments, the HKSAR Government will consider the views of the public, as well as those of interested professional bodies, trade associations and various stakeholders, including the Joint Liaison Committee on Taxation (JLCT). 80 The HKSAR’s budgetary policy, partly as a requirement of Part V of the Basic Law, has been to maintain surpluses and have a low tax policy.81 In particular, Articles 107 and 108 provide: 77 See Sawyer, op. cit. (note 12). 78 Scott, I., The Public Sector in Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2010, page 158. See Sawyer, op. cit. (note 12). This particular article draws upon the HKSAR’s experiences with attempting to introduce a GST, comparing these to the successful implementation in NZ. 79 80 The JLCT is a discussion forum set up on the initiative of the accountancy and commercial sectors in 1987. It is independent of the HKSAR Government, which discusses various tax issues and reflects the views of the industry to the HKSAR Government. See further Inland Revenue Department of Hong Kong, Ordinances Administered (2015), http://www.ird.gov.hk/eng/abo/ord.htm.,(October 8, 2015). Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (1990), with effect from 1 July 1997; http://www.basiclaw.gov.hk/en/index/, (October 8, 2015). 81 21 Article 107: The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall follow the principle of keeping the expenditure within the limits of revenues in drawing up its budget, and strive to achieve a fiscal balance, avoid deficits and keep the budget commensurate with the growth rate of its gross domestic product. Article 108: The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall practise an independent taxation system. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall, taking the low tax policy previously pursued in Hong Kong as reference, enact laws on its own concerning types of taxes, tax rates, tax reductions, allowances and exemptions, and other matters of taxation. As Fong suggests,82 the strategy of John Tsang (Financial Secretary from 2007), has been to spend the budget surpluses on ‘one off relief measures’, while continuing to strictly control the growth of recurrent expenditure. The second part of Tsang's strategy was to set aside the remaining budget surpluses in fiscal reserves to provide a buffer against further economic downturns and the like. Fong’s study clearly illustrates the highly politicized nature of the budget policy process in the HKSAR, which forms a major component of the HKSAR’s approach to tax policy and (current lack of) reform. In the writer’s view the most significant development in the HKSAR’s tax policy and reform process has been the work of the WGLTFP. As noted in the introduction, the objective of the WGLTFP is to assess, under existing policies, the long-term public expenditure needs and changes in government revenue, and to propose feasible measures with reference to overseas experience. The WGLTFP released its report appraising the HKSAR’s fiscal sustainability in March 2014. 83 As commented in the introduction to this paper, the WGLTFP membership84 is similar in terms of representation to the TWG in NZ, although the TWG was established independently of the NZ Government. The WGLTFP's report focusses on the three core components of fiscal sustainability: economic growth, government revenue, and government expenditure. All three components are expected to growth at rates that are commensurate with one another in line with Article 107. Underlying Fong, B. “The politics of budget surpluses: the case of China’s Hong Kong SAR”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Volume 81, Number 1, 2015, page 134. 82 83 See WGLTFP, op cit. Reports are available at: http://www.fstb.gov.hk/tb/en/report-of-the-working-group-onlongterm-fiscal-planning.htm, (October 8, 2015). In addition to the reports, multimedia resources are provided, including videos and games. This illustrates a novel approach to engage wider sectors of the population in the debate over fiscal reform. 84 In addition to HKSAR government members and officials, non-official members include two academics, two accountants and a representative from the corporate sector. 22 concerns are expressed in relation to the narrow-base for tax revenue (focused on a limited range of direct taxes and transaction taxes) that is volatile, which is coupled with an ageing population and greater demands on healthcare and housing. Importantly, the WGLTFP recommends:85 “… that the main priority on the revenue side is to preserve, stabilise and broaden the revenue base. Specifically, the Government should avoid excessive reliance on direct taxation, step up tax enforcement, and reinforce the “cost recovery”, “user pays” and “polluter pays” principles, and should enhance the tax regime to ensure that the tax structure can meet the long-term needs of Hong Kong and the fiscal pressures in the long run.” The WGLTFP specifically recommends expanding the tax base and that “new revenue sources should not be ruled out.” 86 Later on the WGLTFP observes:87 “… in the absence of a goods and services tax and with over 40% of non-tax revenue coming from land premium, the revenue streams for Hong Kong are more vulnerable to economic downturns as compared with other countries. To avoid excessive reliance on direct taxation, the Government should accord more priority to indirect taxation and other non-tax forms of revenue collection. Indirect tax items which have not been adjusted for years should be reviewed. Revenue from indirect tax on consumption goods such as tobacco duty and motor vehicles first registration tax should be protected to combat tax evasion. …. The Working Group recommends that the Government should continue to enhance the tax regime to ensure that the tax structure can meet with the long-term needs of Hong Kong and the fiscal pressures in the long run. While the long-term possibility of introducing new taxes should not be ruled out, the Working Group notes that steps to broaden the tax base are bound to be controversial, as evidenced by the lack of public support for a proposed goods and services tax in the context of the Government’s public consultation on tax reform conducted in 2006.” The HKSAR Government’s response to the report has been to initiate government-wide measures to contain the growth of government expenditure and to review the scope for revenue reforms.88 More specifically:89 85 See WGLTFP, op. cit., para 53 in the Executive Summary (italics emphasis added). 86 WGLTFP, op. cit., para 7.31. 87 WGLTFP, op. cit., paras 7.32, and 7.39 (italics emphasis added). 88 WGLTFP, op. cit., (Phase 2), para 8. 89 WGLTFP, op. cit., (Phase 2), paras 3.10 and 3.11 (italics emphasis added). 23 “The Financial Secretary has also committed to exploring ways to broaden the revenue base. To avoid excessive reliance on direct taxation, the Government has accorded more priority to indirect taxation and other forms of non-tax revenue collection and will continue to do so. The Government will include indirect tax items, in particular those which have not been adjusted for years, as subjects for regular review. In considering the various options on broadening tax revenue in future, the Financial Secretary will have regard to whether the option is effective in broadening the revenue base, fair and in line with the "capacity to pay" principle, and in line with Hong Kong’s simple and low tax system.” Thus not only has the WGLTFP provided some much needed guidance to the HKSAR with respect to reviewing its revenue regime, but the recommendations have been taken on board by the HKSAR Government, in principle at least, even if tangible change remains to be seen. The writer awaits further progress in this area with interest. The Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants (HKICPA), one of the leading private organizations that provide input into tax policy consultation in the HKSAR, has suggested what for the HKSAR would be a radical proposal following consultation on the 2015-2106 budget proposals.90 Specifically, the HKICPA recommends establishing a Tax Policy Unit (TPU) with the objective of strengthening and safeguarding the HKSAR’s long-term position as a leading financial and commercial centre. The TPU would conduct ongoing strategic and comparative research into Hong Kong’s tax competitiveness, monitor international developments in tax administration and make appropriate recommendations. The TPU would comprise representatives from the Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau (FSTB), investment promotion agencies, as well as outside experts and academics. In many respects this would be similar to the TWG in NZ, but whether it would be ‘independent’ of the HKSAR Government is an unresolved matter. What is there to learn from the preceding analysis? Rather than focus on issues such as whether the HKSAR Government should have promoted a GST or had more comprehensive debate on whether it should expand its narrow tax base, this paper suggests that the approach to tax policy development in the HKSAR is in need of serious review. To that end, consideration of NZ’s GTPP (and to a lesser extent the TWG and the HTR in Australia), provides an alternative and informative approach that could potentially be adapted to fit the HKSAR environment. Variations should be made so as to retain the desirable features of both the HKSAR’s legal system, while incorporating 90 HKICPA, Tax policy and budget proposals 2015-16: Planning for Hong Kong’s Future, HKICPA, 2015. 24 the inherent benefits of the GTPP for reviewing tax policy, consultative debate and legislative enactment. The writer hopes that the case has been made for promoting the GTPP as a world-class model for tax policy reform that facilitates the development of high quality technically sound legislation. Furthermore, the GTPP has enabled much of the unnecessary 'politics' to be removed from the reform process, other than in establishing the broad fiscal and revenue strategy. However, the GTPP may not be easily transferrable, and it is premised on a transparent and consultative approach to tax policy development. Furthermore, should the HKSAR look to undertake tax reform, it could also evaluate the HTR Review and TWG models, the latter being an independent and well-resourced body operating outside of the government. These models could complement an HKSAR-styled tax policy process that supports the necessary ‘politics’ of tax policy analysis with input from the wider public and private sectors. The WGLTFP is a positive start for the HKSAR as it takes tentative steps down the path of reviewing its tax regime and contemplating more structured and informed tax reform. 5. Concluding Observations and Insights from the Australian Tax Policy Process, and New Zealand’s GTPP and TWG for the HKSAR Readers are invited to explore the in-depth suggestions offered by Sawyer and others with respect to NZ’s GTPP and TWG, and how these could be adapted for the HKSAR.91 In summary, while there are major differences between Australia and NZ, these differences do not necessarily prevent the development of a tax policy process based upon the GTPP model that could fit within the HKSAR’s legislative structure, or the use of tax reform bodies. The latter has been illustrated by the establishment of the WGLTFP, and in the proposal of the HKICPA discussed in the previous section of this paper. However, what is important, is greater transparency and consultation through the IRD and HKSAR’s FSTB undertaking rigorous analysis of the tax system. Such analysis should lead to critical policy issues being raised with the HKSAR Government, plus the release of consultation documents inviting public submissions. In order to achieve this, it may be necessary to increase the skill base of the IRD and FSTB in the HKSAR, perhaps supplemented by external consultants. The WGLTFP and the HKICPA's proposal are positive steps in this direction. From an HKSAR perspective, reform of the tax system (revenue regime), in any format, is not something that is tackled frequently, and arguably it is not something that should be regularly on 91 See Sawyer, op. cit. (note 6). See also Little et al, op. cit. 25 the agenda. Nevertheless, the WGLTFP has recognized the need for the HKSAR to review its fiscal policy, with the HKSAR Government accepting this position in principle. In this paper the writer has sought to offer to a jurisdiction that has struggled with implementing tax reform (the HKSAR) the example of how two other jurisdictions (Australia and NZ) have been successful in major tax reform. The reason for this success is largely attributable to NZ's innovative world-class model for tax policy development, refinement and review (the GTPP), as well as (to a lesser degree) the establishing of bodies (which has been fully resourced by government officials) to review the tax structure and offer well-researched options for public consultation and review by the government (the HTR and TWG). It is useful at this point to reflect on the extent to which Australia and NZ have adopted the principles that underlie effective tax policy reform, which in turn could prove a useful benchmark for the HKSAR to assess it approach to tax reform. Table 1 sets out the author’s preliminary assessment in this regard. Table 1: Tax Reform Principles: A Comparison Tax Policy Principle Australia (HTR) New Zealand (TWG) HKSAR The existence of a ‘vision’ Yes Yes Emerging Sound economic principles Yes Yes Yes The political dimension Challenging Supportive Challenging A political champion Not clearly Ministers of Finance and Revenue Not clearly one yet Constitutional and other factors Difficulty of States and no GST None ‘Democracy’ challenges and PRC A package of reforms Partially Yes Too early to tell An appetite for reform Some Plenty Not convinced (as yet) Future research should include reassessing the situation in the next twelve months to see what consultative documents and proposals emerge from the Chief Executive and HKSAR Government. Hopefully the proposals will not only test the political mood for undertaking tax reform and establishing a more rigorous model for tax reform, but also signal the direction for reform as the HKSAR addresses issues over its long term fiscal challenges. While it is acknowledged by the HKSAR that it faces an ever-aging population and increased healthcare needs, plus extraordinarily 26 high land prices and rent, the pressing need for long term fiscal reform have been recognized. Reform of the HKSAR’s tax regime is in the writer’s view inevitable, although this should not mean that its desirable features (such as its relative simplicity) should be removed. The future may suggest a move towards something closer to a NZ BBLR model, emphasizing a broadening of the base into more indirect taxation, and maintaining low rates. This paper has a number of limitations, the most important being the comments reflect those of an ‘outsider’, rather than someone closely involved with the HKSAR’s political and business activities and negotiations. That said it is an advantage, in that being an outsider, one is more freely to offer a critical realist’s perspective without the limitations of secrecy and restrictions on publicly commenting on matters of national importance associated with one’s occupation, particularly as a government official or someone closely aligned with the jurisdiction. Furthermore, this paper also has a limitation in that the author is less familiar with the Australian approach to tax policy reform, being more reliant upon assessing the views of others. A more significant limitation is that the HKSAR’s tax reform has to date taken only the first tentative steps towards revisiting (and perhaps renovating) its revenue regime. Thus this paper by no means seeks to be the final word as the issues addressed remain in a state of flux as at the time of writing. 27