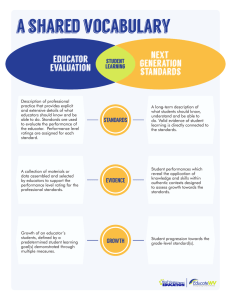

Massachusetts State Equity Plan 2015-2019

advertisement