PrincipalAdvisorySummary

advertisement

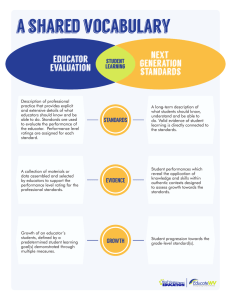

Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Purpose From 2011 to 2014, ESE convened two principal advisory cabinets: an elementary principal advisory cabinet comprised of preK-grade 5 school-level administrators, and a secondary school principal cabinet comprised of middle and high school administrators. Focused exclusively on the new educator evaluation framework in Massachusetts, these two cabinets met quarterly to share successes and challenges related to implementation of the new educator evaluation framework and were a key component of fulfilling the Educator Evaluation’s Team’s mission related to engaging school-based educators in the ongoing refinement of the new framework, evaluating implementation, and gathering feedback on resource and guidance creation. The principal advisory cabinet structure led to parallel teacher and superintendent advisory cabinets in 2013-2014. Educator Evaluation Team Mission To improve professional growth and student learning, ESE is committed to ensuring the success of the statewide Educator Evaluation framework by providing educators with training materials and resources, meaningful guidance, and timely communications, and by engaging educators in the development and ongoing refinement of the framework. Contents This report includes the following summary information about the 2011-2014 ESE Principal Advisory Cabinets: Background Key Takeaways Principal Cabinet Recommendations Yearly Summaries (Year 1, Year 2, Year 3) Moving Forward (2014-15 Educator Effectiveness Principal Advisory Cabinet) 2011-2014 Meeting Topics Cabinet Membership by Region Cabinet Members Background The principal cabinets began meeting in August 2011, shortly after passage of the new educator evaluation regulations (603 CMR 35.00). The first participants were members of the boards of the two state principals associations, MA Elementary School Principals Association (MESPA) and MA Secondary School Administrators’ Associations (MSSAA), and were identified by these organizations to participate. The MESPA (elementary) cabinet initially included four members and the MSSAA (secondary) cabinet included six members, each of whom came from Race to the Top (RTTT)1 districts across the Commonwealth. In the 2012–13 and 2013–14 school years, the principal cabinets expanded to include administrators from nonRTTT districts, as well as assistant principals, charter school administrators, and representatives from educator preparation. Cabinet members were instrumental in providing insight into the successes and challenges of implementation. Members also continued to provide feedback on resources and elements of the Model System, as well as the guidance on performance ratings, student and staff feedback instruments, evaluator calibration challenges, and training materials. 1 The MA educator evaluation framework was phased in over a period of three years. Thirty-four early adopter districts began piloting the new framework during the 2011–12 school year, all Race to the Top (RTTT) districts began implementing the new framework during the 2012–13 school year, and all non-RTTT districts began implementing in 2013–14 school year. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 1 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Key Takeaways The thought-provoking conversations between principal cabinet members and ESE’s Educator Evaluation Team offered critical insights into the challenges and opportunities of implementing the educator evaluation framework during the first three years. Although implementation and the use of resources, which vary from school to school, are affected by logistical factors such as elementary versus secondary structures and the number of administrators in a school, it is evident that principal leadership is essential to effective implementation. Principals play a vital role in shaping school culture and perceptions of the educator evaluation framework; communicating essential information and setting expectations; and accessing, using, and translating resources to school staff. In this section, ESE shares key takeaways that can inform school and district leaders as they continue to refine implementation of the new framework. Impact Through new educator evaluation systems, principals are seeing an early and powerful impact on school-level conversations. Cabinet members described a shift toward a focus on teaching and learning, using terms like “common language” and “honest conversations.” They noted that without the new evaluation framework, there would have been many “missed opportunities.” Principals identified self-assessment and goal setting as critical to developing this shared language and greater focus on instruction and student outcomes. TIP: Participants agreed that the most effective strategy to foster these conversations is to strategically introduce the performance rubric, breaking it down into manageable chunks. TIP: Principals who conducted multiple, short, unannounced observations followed-up with immediate feedback found that ongoing dialogue between evaluators and educators grew more meaningful over time. Training Participants noted that principals have often led all of the educator evaluation training, especially with teachers. While this provides an opportunity for local customization, many principals felt as if they were learning it as they taught it, which created challenges when answering questions. Cabinet members also shared that schools and districts who prioritized ESE’s training Module 6 (Observations and Feedback) over Module 5 (Gathering Evidence) later found that there was significant confusion about evidence collection. Lastly, participants identified a need to ensure consistency through ongoing work to calibrate evaluator skills and expectations. TIP: Ensure that Module 5: Gathering Evidence and/or Teacher Workshop 4: Gathering Evidence are key components of school-level professional development. TIP: Principals found that looking at the same type of evidence across multiple educators helps evaluators benchmark practice and cultivate a common understanding around what good practice looks like. TIP: It is important for districts to bring evaluators together on a regular basis to engage in calibration exercises examining authentic artifacts and discussing practice and feedback. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 2 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Implementation A number of practical lessons emerged regarding implementation. Technology supports. Principals found technology supports critical to managing the 5-step cycle, particularly when used to facilitate evidence collection. Principals also found it useful to access existing technology, such as wiki pages used by educators or Google Docs, to store and disseminate instructional materials. Evaluator Workload. Principals found that the workload for evaluators substantially increased the second half of the school year, due to conducting observations, analyzing evidence, writing up reports, and meeting with educators about formative assessments, formative evaluations (for educators at the end of year one of a two-year cycle) and summative evaluations. TIP: Conducting more observations before winter break will help evaluators balance their workload. Evidence Collection. Cabinet members agreed that evidence collection practices vary widely, even within schools. Educators still need clarity around what types of evidence to collect, why, and how much. For example, some evaluators ask for “no more than two pieces of paper” while others expect a binder of evidence spanning the whole school year. The principals also noted that Standard III (Family and Community Engagement) and Standard IV (Professional Culture) are the most difficult to demonstrate via evidence. TIP: Districts and/or schools should set consistent expectations for evidence collection. Questions to address may include: is evidence expected at the level of the Standard, Indicator, and/or element? Which ones? How many pieces of evidence are required? What does high quality evidence look like? Districts have found that collecting and disseminating examples of evidence reduces teacher confusion and creates greater consistency across evaluators. Identifying concrete pieces of evidence at the beginning of the educator plan also ensures clarity and common expectations. For additional support, please see ESE’s Training Module 5 and Teacher Workshop 4, both on Gathering Evidence, as well as ESE’s Evidence Collection Toolkit, and the August 2014 Educator Evaluation Newsletter Spotlight. Principal evaluation. School and districts have focused on teacher evaluations, often at the expense of principal evaluations. Principal evaluation, however, provides a critical opportunity for schools to model the process and impact school culture by showing they’re “all in this together.” TIP: Given the importance of modeling common practice, principals should prioritize self-assessing, goal setting, and creating their own educator plans at the beginning of the year (focusing on alignment to school and district improvement plans), and draw from this experience to support teachers in Steps 1 and 2 of their evaluation cycles. Communication. Principals are simultaneously learning and trying to teach others about the components of the educator evaluation system; they rely on having accurate, timely, and sufficient information to be able to communicate effectively with their teachers. Communication channels to school-level educators are often inconsistent and are typically dependent on the superintendent. TIP: In addition to superintendents consistently sharing information and resources from ESE and other districts with their principals in meetings, via email, and other methods such as a newsletter or wiki page, districts can appoint multiple people, including principals and teacher leaders, as Educator Evaluation contacts in ESE’s Directory Administration to ensure that information from ESE goes directly to schoollevel administrators. For more information about how to assign a person as an Educator Evaluation Contact, please review the Directory Administration Guide at http://www.doe.mass.edu/infoservices/data/diradmin/. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 3 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Principal Cabinet Recommendations The principal cabinets provided actionable input to ESE around educator evaluation implementation. As a direct result of these recommendations, ESE improved communication with the field, prioritized resources, and refined guidance. The table below highlights specific recommendations and ESE’s responses. Principal Cabinet Recommendation Strategic communication with educators in the field: Find ways to connect directly with educators in the field through the use of newsletters and other regular communication vehicles. Highlight rolespecific resources for principals and teachers. Examples of principal observation: Acknowledge the multiple purposes of superintendents’ school visits and provide examples of appropriate opportunities for superintendents to observe school leaders in action. Adjustments to the Administrator rubric: ESE’s Responses Based on feedback from these school-level administrators, ESE launched a variety of communication tools to provide user-friendly guides and resources, including 2-page Quick Reference Guides (QRGs) on elements of the evaluation framework, and a monthly newsletter spotlighting best practices, highlighting pertinent resources, and announcing new information and resources. ESE also reorganized the educator evaluation forms posted on the website by educator/evaluator role per the group’s recommendation, and identified Educator Evaluation Contacts in every district to receive targeted information about the evaluation model. ESE developed Appendix B: Protocol for Superintendent’s School Visits to accompany the Implementation Guide for Principal Evaluation (Part V of the Model System). ESE refined the Exemplary performance level definition throughout the Administrator rubric. Clarify language distinguishing between performance levels. Additional resources to support the Model System: Provide more support for educators around self-assessment, goal setting, and gathering evidence through multiple avenues, especially exemplars. Guidance on feedback collection and use: Provide additional clarity around the formative use of feedback in an educator’s evaluation ESE prioritized the development of the following resources based on cabinet member feedback: S.M.A.R.T. Goal Development Protocol Evidence Collection Toolkit Guide to Role Specific Indicators and Additional Resources for SISP educators ESE will be producing resources to assist evaluators in incorporating feedback into an educator’s evaluation, including information about the role of feedback as evidence, and how to have meaningful dialogue with an educator about feedback. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 4 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Principal Cabinet Recommendation Supports for evaluator calibration: Identify best practices related to calibrating evaluators within and across schools and provide protocols that allow for flexibility. Alleviate evaluator workload: Support technology platforms that will assist evaluators in gathering and managing information and alleviate burden on time required to complete all evaluation activities. ESE’s Responses ESE will be developing new training supports for evaluators in 2014-15, including video and resource examples tied to the 5-step cycle of evaluation. In 2014-15, ESE will be developing Professional Learning Networks comprised of select districts to identify and develop high-quality practices related to evaluator skill development. ESE released the 2013 Technology Innovation Grant, supporting partnerships with technology vendors in three MA districts to develop and refine platforms in support of educator evaluation implementation. In 2014-15, ESE will be developing Professional Learning Networks of select districts to explore models for distributed leadership and more effective data management solutions. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 5 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Yearly Summaries Year 1: 2011–2012 The 2011-2012 cabinets were comprised of ten members representing suburban and rural RTTT districts. Given ESE’s existing engagement with large, urban districts, the cabinets were intentionally focused on representing smaller districts in less urban areas of the Commonwealth. ESE Model System. The 2011-2012 school year was the first implementation year for RTTT districts, who were required to evaluate at least 50% of their educators under the new framework. Cabinet members were charged with providing targeted feedback on the development of the ESE Model System for Educator Evaluation, including the evaluation model processes for superintendents (Part VI) and principals (Part V), as well as the ESE model rubrics for school-level administrators and teachers (Part III of the Model System). PERFORMANCE RUBRICS Cabinet members contributed specific feedback to content and performance descriptors in ESE model rubrics for both principals and teachers, such as an emphasis on the provision of common planning time for teachers (St. I: Instructional Leadership), and clearer distinctions made between Proficient and Exemplary practice. Implementation Feedback. Principals also provided feedback on school-level implementation processes that would be new to both teachers and administrators, including goal-setting, unannounced observations, and the provision of feedback. They underscored both technical and adaptive challenges associated with more frequent, unannounced observations and the provision of ongoing feedback, particularly in schools that are more accustomed to announced observations with pre- and post-conferences. This input directly informed model processes for the ESE School Level Implementation Guide (Part II), which included concrete forms and 1-page resources to assist educators and evaluators in the implementation of the new framework. ADMINISTRATOR S.M.A.R.T. GOALS One recommendation to emerge from principal cabinets was to encourage the development of “2-4 goals related directly to school improvement priorities and district improvement priorities for the year” as a means of ensuring coherence and relevance for administrator S.M.A.R.T. goals. Training Program. Meetings in the latter half of the year focused on appropriate content for required training modules for evaluators and school leadership teams, including a review of the proposed 8-part series, recommendations on effective delivery mechanisms, and the development of exemplars. Principals also underscored the importance of identifying technology supports for efficient data management and smooth implementation, a recommendation that would inform ESE’s Technology Innovation Grant in the subsequent year. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 6 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Year 2: 2012–2013 In 2012-2013, the principal cabinets’ memberships expanded to include assistant principals, many of whose roles changed dramatically under the new regulations. The 2012-2013 cabinets each had seven members and included school leaders from urban, suburban, and rural districts. Implementation Feedback. The 2012–2013 school year was the first year of full implementation in RTTT districts, and the first year of implementation with at least 50% of educators in non-RTTT districts. Cabinet members provided insight into the successes and challenges related to implementing each step of the 5-step evaluation cycle, as well as the utility and effectiveness of the ESE training programs for evaluators and teachers. Principal Feedback on 5-Step Cycle Steps 1 and 2 (Self-Assessment & Goal Setting): Breaking the rubric down into manageable pieces helps educators conduct their self-assessments and identify targeted goals. Principals still struggle with supporting SISP educators in Steps 1 and 2 and would benefit from more targeted resources. Step 3 (Implementation): Evidence collection varies widely and there is a lack of consistency in evidence quality and quantity. Multiple observations result in ongoing and more meaningful feedback, but it’s challenging to find time to do them. Standards III and IV are the most difficult to demonstrate through evidence. Step 4 (Formative Assessments): time-consuming, even if only for non-PTS educators, as administrators become accustomed to the process. Step 5 (Formative/Summative Evaluations): felt like a “tsunami;” technology supports are critical to manage this process. While educator burden is heaviest at the beginning of the cycle, evaluator burden is heaviest at the end of the cycle. Communications. Cabinet members agreed that there remained widespread misinformation about the new evaluation model with both teachers and school-level administrators. While ESE was regularly communicating with district leaders, ESE communications channels to school level educators were inconsistent and too dependent on the superintendent sharing information with principals. Direct communications to school-level educators should be highly strategic, however, to avoid overburdening educators with email. They recommended more role-specific resource dissemination, streamlined, targeted messaging to teachers, and stronger partnerships with state associations. In response, ESE launched its monthly Educator Evaluation Newsletter in February 2013, designed to disseminate information on resources, tools, and innovative practices from the field. Implementation Resources. Members continued to provide feedback on implementation resources under development, including training modules and workshops, performance ratings guidance, and staff and student feedback. Practices related to conducting observations, providing feedback, and collecting evidence continue to represent a “huge culture shift” for educators and require additional clarity and support from ESE, over and above Modules 5 and 6, leading ESE to develop an “evidence collection toolkit” for district and school leaders. Principal feedback on performance rating guidance also revealed conflicting opinions about the degree of flexibility that should be afforded to an evaluator (secondary school administrators preferred a more prescriptive process while elementary school leaders supported more evaluator-specific professional judgment). This nuanced feedback contributed directly to performance ratings guidance and related scenario-based worksheets that underscored the role of professional judgment within the regulatory requirements associated with performance ratings. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 7 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Year 3: 2013–2014 The 2013-2014 secondary and elementary cabinets had twelve and eight members, respectively, and included administrators from urban, suburban, and rural districts, general and vocational/technical schools, and RTTT and non-RTTT districts, as well as representatives from charter schools and educator preparation programs. Evaluator Calibration. Cabinet members continually emphasized the importance of ongoing calibration training and/or activities for evaluators, both within schools and across schools. “Teachers know it” when evaluators do not share common understanding of processes related to evidence collection, observations, and feedback, and inconsistency can undermine buy-in to the evaluation model. Principals shared examples of calibration practices ranging from district-wide, ongoing training sessions (weekly or monthly) to less formal calibration sessions during leadership team meetings. Calibration activities tended to focus on specific evaluator skills, such as providing high quality feedback or identifying “proficient” practice during observation. Cabinet members recommended the development of additional resources and supports to support evaluator calibration, such as videos, exemplars, and protocols that would establish basic criteria around evaluator skills while allowing for more customization to meet school and district needs. Student & Staff Feedback. Cabinet members provided input across several meetings on the effective administration of feedback surveys, potential implementation challenges, content of survey reports, and appropriate use of feedback data. In addition to emphasizing close alignment between survey items and the MA performance rubrics, principals recommended the incorporation of open response items to ESE model surveys, as well as item-level and Indicator-level data reporting. Principal feedback on the ESE guidance stressed the importance of ensuring the anonymity of respondents, particularly with regard to teacher surveys, and shared their experiences with existing feedback instruments, such as exit slips or school climate surveys. The overarching recommendation of cabinet members was to emphasize the formative use of feedback in an educator’s evaluation, particularly with regard to the self-assessment and goal setting steps of the evaluation cycle. ESE incorporated their input throughout the development of the guidance document on staff and student feedback (released in summer 2014), which included recommendations about survey administration and the use of survey results for formative purposes (e.g. reflecting on and adjusting practice). Principal Feedback on Overall Evaluation Framework Successes More meaningful dialogue between teachers and evaluators around teaching & learning Setting of high expectations around student learning and engagement Goal-setting and evidence collection became more intentional and meaningful Student-centered goal-setting Teacher-led DDM development Implementation of distributed leadership structures Increased trust and buy-in Use of formative assessments to promote growth & development Ongoing Challenges A focus on compliance vs. intention/impact (esp. re: district determined measures) Time management around classroom observations Calibrating evaluator feedback Balancing multiple initiatives To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 8 of 12 Educator Evaluation: Principal Advisory Cabinets 2011-2014 Moving Forward 2014–2015 Educator Effectiveness Principal Cabinets In 2014-15, ESE’s Educator Development Team is reconstituting the principal advisory cabinet from an advisory group focused on educator evaluation, to an advisory group dedicated to all major initiatives related to educator effectiveness. The 2014-15 Educator Effectiveness Principal Cabinets will bring elementary and secondary administrators together in two regional cabinets: one in Malden, MA and one in the Central/West region of the state. Membership will be determined through an application process. Representatives from the state principals’ associations, MSSAA and MESPA, will maintain permanent membership, as will the MESPA and MSSAA Principals of the Year. The focus of the cabinets will remain twofold: ESE hopes to continue to learn from school leaders about implementation, and to seek their feedback on existing and upcoming resources. Potential topics for feedback during the 2014-2015 school year include peer assistance and review, teacher leadership, differentiated supports, evaluator training, district-determined measures, resources around evidence collection, goal exemplars, communication strategies, and connections with educator preparation programs. The work of the 2013-14 Educator Effectiveness Principal Cabinets will closely mirror that of parallel Teacher and Superintendent Advisory cabinets throughout the year. To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 9 of 12 x x x x x Summer 2012 Fall 2012 Spring 2013 x Summer 2013 Fall 2013 Winter 2014 Spring 2014 x x x X x x x x x x x x Implementation & Training Supports To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 10 of 12 DDMs x X Development of ESE Model System Student & Staff Feedback x x Evaluator Calibration x x Implementation Feedback Training Modules Goal Setting Collective Bargaining Implementation Supports Observations and Feedback x Communications x Performance Rubrics ESE Model: Supt. Evaluations ESE Model: Teacher Evaluations x Teacher Workshops x x x 2012-13 Meetings Summer 2011 Fall 2011 Winter 2011 Spring 2012 2013-14 2011-12 TOPICS ESE Model: Principal Evaluation 2011-2014 Cabinet Meeting Topics x x x New Implementation Resources Cabinet Membership by Region Red: 2011-2012 Cabinet Members Green: 2012-2013 Cabinet Members Blue: 2013-2014 Cabinet Members (circled icons indicate membership across multiple years) To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 11 of 12 Cabinet Membership, 2011–2014 Secondary Schools Principal Cabinet Elementary Schools Principal Cabinet Dana Brown Malden Public Schools Tom LaValley Salem Public Schools Dan Richards Belmont Public Schools Denise Fronius Brewster Public Schools Greg Myers Quaboag Regional Sue Driscoll Falmouth Public Schools Tricia Puglisi Manchester-Essex Regional Marie Pratt Longmeadow Public Schools Dave Thomson Bridgewater-Raynham Regional Kathy Podesky Mansfield Public Schools Joe Connor Attleboro Public Schools Kelly Hung Boston Public Schools Shannon Snow South Middlesex Reg Voc Tech Peter Crisafulli Whately Public Schools Steve Pechinsky Revere Public Schools Jason DiCarlo Lowell Public Schools Kim McParland Dover-Sherborn Tim Lee Lenox Public Schools Lawrence Murphy West Boylston Public Schools Ellen Stockdale Whitman-Hansen Jonathan Pizzi Needham Public Schools Deb Dancy Boston Public Schools Sarah Morland Boston Collegiate Charter School Jane Gilmore University of MA—Lowell Anthony Ciccariello Somerville Public Schools Nadya Higgins MESPA Sharon Hansen Avon Public Schools Maureen Cohen Grafton Public Schools Richard Pearson MSSAA To offer suggestions, pose questions, or receive updates on ESE’s implementation efforts, please email EducatorEvaluation@doe.mass.edu. Page 12 of 12