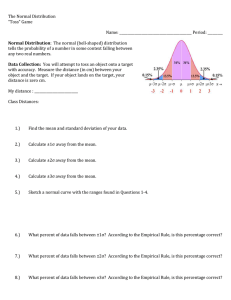

Word Format Here

advertisement