Academic Senate - Self Review Report [.DOC]

advertisement

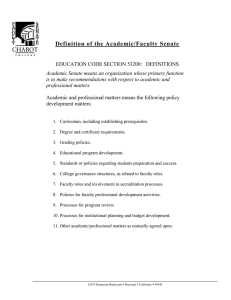

![Academic Senate - Self Review Report [.DOC]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015120687_1-874ccf0ba09d76db6665b89ad9499ce8-768x994.png)