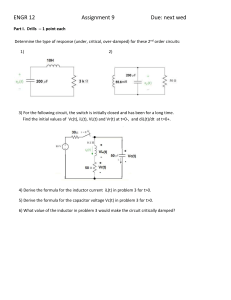

Inductor-capacitor "tank" circuit

advertisement

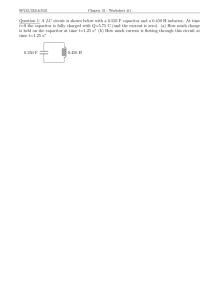

Inductor-capacitor "tank" circuit PARTS AND MATERIALS Oscilloscope Assortment of non-polarized capacitors (0.1 µF to 10 µF) Step-down power transformer (120V / 6 V) 10 kΩ resistors Six-volt battery The power transformer is used simply as an inductor, with only one winding connected. The unused winding should be left open. A simple iron core, singlewinding inductor (sometimes known as a choke) may also be used, but such inductors are more difficult to obtain than power transformers. CROSS-REFERENCES Lessons In Electric Circuits, Volume 2, chapter 6: "Resonance" LEARNING OBJECTIVES How to build a resonant circuit Effects of capacitor size on resonant frequency How to produce antiresonance SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM ILLUSTRATION 1 INSTRUCTIONS If an inductor and a capacitor are connected in parallel with each other, and then briefly energized by connection to a DC voltage source, oscillations will ensue as energy is exchanged from the capacitor to inductor and visa-versa. These oscillations may be viewed with an oscilloscope connected in parallel with the inductor/capacitor circuit. Parallel inductor/capacitor circuits are commonly known as tank circuits. Important note: I recommend against using a PC/sound card as an oscilloscope for this experiment, because very high voltages can be generated by the inductor when the battery is disconnected (inductive "kickback"). These high voltages will surely damage the sound card's input, and perhaps other portions of the computer as well. A tank circuit's natural frequency, called the resonant frequency, is determined by the size of the inductor and the size of the capacitor, according to the following equation: 2 Many small power transformers have primary (120 volt) winding inductances of approximately 1 H. Use this figure as a rough estimate of inductance for your circuit to calculate expected oscillation frequency. Ideally, the oscillations produced by a tank circuit continue indefinitely. Realistically, oscillations will decay in amplitude over the course of several cycles due to the resistive and magnetic losses of the inductor. Inductors with a high "Q" rating will, of course, produce longer-lasting oscillations than low-Q inductors. Try changing capacitor values and noting the effect on oscillation frequency. You might notice changes in the duration of oscillations as well, due to capacitor size. Since you know how to calculate resonant frequency from inductance and capacitance, can you figure out a way to calculate inductor inductance from known values of circuit capacitance (as measured by a capacitance meter) and resonant frequency (as measured by an oscilloscope)? Resistance may be intentionally added to the circuit -- either in series or parallel - for the express purpose of dampening oscillations. This effect of resistance dampening tank circuit oscillation is known as antiresonance. It is analogous to the action of a shock absorber in dampening the bouncing of a car after striking a bump in the road. COMPUTER SIMULATION Schematic with SPICE node numbers: Rstray is placed in the circuit to dampen oscillations and produce a more realistic simulation. A lower Rstray value causes longer-lived oscillations because less energy is dissipated. Eliminating this resistor from the circuit results in endless oscillation. 3 Netlist (make a text file containing the following text, verbatim): tank circuit with loss l1 1 0 1 ic=0 rstray 1 2 1000 c1 2 0 0.1u ic=6 .tran 0.1m 20m uic .plot tran v(1,0) .end RESUME OF THEORY FOR PARTS 1 AND 2 Inductors (L) and Capacitors (C) can actually store electrical energy. This is unlike Resistors in which energy is only dissipated. Once stored, this energy is available for release. Ideal Inductors and Capacitors dissipate no energy. The Inductor and Capacitor, like the Resistor, are Circuit elements with two terminals. As such, the relationship between voltage across (v) and current (i) through their terminals can be defined just as Ohms Law defines the relationship between these variables (v and i) for a resistor. Circuit Element Resistor Inductor Capacitor v =f(i) i = f(v) v i R di v L dt i v R t 1 v idt vt0 C t0 Power dissipated P i2 R 1 vdt it0 L t0 i C dv dt Nil Nil W 1 2 Li 2 Nil W 1 2 Cv 2 t i Energy stored 4 RESUME OF THEORY FOR PARTS 3 AND 4 Energy delivered by a source can be stored in an inductor or capacitor and this energy can be returned to the source. No resistance is inserted into any of the circuits so far, except for the small resistance in the switches that is made negligible. The question that arises once resistance is inserted is how would the energy stored in these components be delivered to a resistor. A resistor dissipates energy (as heat). It stores no energy. It is a fair assumption to make that the energy stored in an inductor or capacitor would decay with time once a path was provided for it to flow to a resistor. The object is to specify the mathematical relationship that this decay with time follows. Once initial conditions are known, a voltage in an capacitor (V0) and current in an inductor (I0), the application of Kirchoff’s laws results in the circuit equations that will yield the voltage and current relationships with time. The definitions of the current/voltage relationships are applied for the storage elements and for resistors (Ohm’s Law) and first order ordinary differential equations result. The solution leads to equations that define an exponential decay with time of any energy that is stored. Current Inductor i (t ) I 0 e Capacitor N/A Voltage R t L N/A v(t ) V0e t RC Time Power Constant 2 t L t p I 02 Re R RC V0 2 t2 t p e R Energy 2 t 1 LI 02 (1 e t ) 2 2 t 1 w CV02 (1 e t ) 2 w In both instances, the decay in current and voltage is exponential with time. In both instances, the power delivered to the resistor decays exponentially with time. In both instances, as time progresses, the energy dissipated in the resistor approaches the initial energy stored in the inductor or capacitor. If there are no initial conditions the stored energy in the inductor or capacitor is zero so no energy is dissipated in the resistor. The time constant t is defined as shown to characterize the exponential decay in energy in the inductor/capacitor (or growth in the case of energy dissipated in the resistor). It does this through the factor e-t/t. After a time interval of 5 time constants, the factor is less than 1% of its initial value. t t t t e 3.6788x10-1 t 6t t t e 2.4788x10-3 5 2t 3t 4t 5t 1.3534x10-1 4.9787x10-2 1.8316x10-2 6.7379x10-3 7t 8t 9t 10t 9.1188x10-4 3.3546x10-4 1.2341x10-4 4.5400x10-5 As will be seen, the time constant is usually very much smaller than a second. The appearance/disappearance of currents and voltages are momentary events and are referred to as the TRANSIENT RESPONSE of the circuit. The response that exists a long time after switching has taken place is called the STEADY STATE RESPONSE 6 RESUME OF THEORY FOR PARTS 5 AND 6 Energy delivered by a source can be stored in an inductor or capacitor. A resistor resists the flow of current. A fair assumption to make is that there will be a build up of energy in an inductor or capacitor but the rate will be determined by the size of the resistor. The object is to specify the mathematical relationship that this build up with time follows. Once initial conditions are known, a voltage in an capacitor (V0) and current in an inductor (I0), the application of Kirchoff’s laws results in the circuit equations that will yield the voltage and current relationships with time. The definitions of the current/voltage relationships are applied for the storage elements and for resistors (Ohm’s Law) and again, first order ordinary differential equations result. The solution leads to equations that define an exponential build up with time of any energy that is stored. Inductor Current V V ( R )t i (t ) s ( I 0 s )e L R R t0 Vs ( R )t (1 e L ) R t 0 Provided I 0 0 Capacitor N/A Voltage N/A Time Constant L R i (t ) v (t ) I s R (V0 I s R)e t0 v (t ) I s R(1 e t0 ( 1 RC ) t ( 1 RC ) t RC ) Provided V0 0 In both instances, the growth in current and voltage is exponential with time to a final value determined by the circuit. The time constant t is defined as shown to characterize the exponential growth in current/voltage in the inductor/capacitor. It does this through the factor e-t/t. After a time interval of 5 time constants, the factor is within 1% of its final value. 7 RESUME OF THEORY FOR PARTS 7 Ideal OPAMP Input resistance Input Currents Rules Infinite Zero Consequence ip=in Voltage Gain Input voltages Infinite Equal vp=vn Virtual Short Condition The rules associated with the OPAMP allow the current through Rs and Cf to be summed to zero using KCL. is i f is 0 1 vo Rs C f vs Rs dv if Cf o dt dvo 1 vs dt RsC f t v dy v (t ) s o o to 8 Type Circuit Section 6.1 Apply Kirchoff i 0 At a node I0 2 + V0 C _ L R Parallel t v dv 1 C vdx I 0 0 R dt L 0 1 0 Natural Initial energy is present. Energy is stored at time t=0. Section 6.3 I0 2 + I V0 _ C 1 0 Initial energy may be present. DC source I supplies energy. Section 6.4 R 1 L v dv C I R dt v 0 2 C di 1 iR L idx V0 0 dt C 0 _ Series 0 Section 6.4 R 1 v 0 2 around a closed loop. C i Divide by LC d 2i L 1 di L i L I 2 dt RC dt LC LC * Vo and to make idx into i 0 2 LC d i di i 0 2 RC dt dt Substitute to eliminate I dvC di d 2v and C 2C dt dt dt 2 d v dv LC 2C CR C vC V dt dt i C I0 + V0 L di L dv d 2i and L 2L dt dt dt 2 d i L di L LC 2L iL I dt R dt d 2i R di i 0 2 dt L dt LC * Initial energy is present. Energy is stored at time t=0. Natural 0 d 2 v L dv LC 2 v 0 dt R dt Divide by LC d 2v 1 dv v 0 2 dt RC dt LC * Substitute to eliminate v t t i t I o and to make vdx into v around a closed loop. Differentiate to remove I0 + V0 i L iR iC I iL Differentiate to remove v L L R Parallel Step i 0 At a node Mathematics V _ Series 0 Initial energy may be present. DC source V supplies energy. iR L di vC V dt Divide by LC d 2 vC R dvC vC V 2 dt L dt LC LC * Step * All 4 circuits are described by second order differential equations. For parallel RLC circuits, the coefficient of the first order differential is R L 1 RC . For Series RLC circuits, the coefficient of the first order differential is . The challenge now is how to solve a second order differential equation. 9 Resume of Theory for Parallel and Series RLC circuits All four circuits result in second order differential equations. The method of solution follows, first for the Natural Response, then for the Step Response. Over damped s1 s2 Under damped s1 s2 v A1e A2 e s1t s2 t Critically Damped s1 s2 v A1e A2 e s1t s2 t s1 2 2 0 s1 2 2 0 s2 2 2 0 1 PARALLEL 2 RC R SERIES 2L 1 0 LC 2 2 0 0 s2 2 2 0 1 PARALLEL 2 RC R SERIES 2L 1 0 LC 2 2 0 0 v A1e s1t A2 e s2t v B1e t cos d t B2 e t sin d t v D1te t D2 e t 1 PARALLEL 2 RC R SERIES 2L 2 02 0 v D1te t D2 e t d 02 2 Constants v (0 ) V0 A1 A2 Constants v (0 ) V0 B1 Constants v (0 ) V0 D2 dv (0 ) iC (0 ) s1 A1 s2 A2 dt C dv (0 ) iC (0 ) B1 d B2 dt C dv (0 ) iC (0 ) D1 D2 dt C Real Roots Exponential Decay Imaginary Roots Exponentially decaying oscillations Exponential Decay For the Step Response, simply determine the final value of the current or voltage and add it to the Natural Response! 10