Public Service and Outreach Commission Report Fall 2000

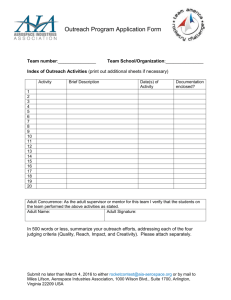

advertisement