Interfacing with ELF files An introduction to the Executable file specification standard

advertisement

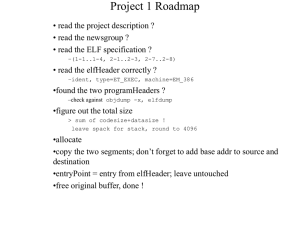

Interfacing with ELF files An introduction to the Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) binary file specification standard Overview of source translation User-created files Makefile Make Utility C/C++ C/C++Source Source and Header and Header Files Files assembler Object Object Files Files Archive Utility Shared Object File Linker Command File preprocessor compiler Library Library Files Files Assembly Assembly Source Source Files Files Linker and Locator Linkable Image File Executable Image File Link Map File Executable versus Linkable ELF Header ELF Header Program-Header Table (optional) Program-Header Table Section 1 Data Segment 1 Data Section 2 Data Segment 2 Data Section 3 Data Segment 3 Data … Section n Data … Segment n Data Section-Header Table Section-Header Table (optional) Linkable File Executable File Role of the Linker ELF Header Section 1 Data Section 2 Data … Section n Data ELF Header Program-Header Table Segment 1 Data Section-Header Table Linkable File Segment 2 Data ELF Header … Segment n Data Section 1 Data Section 2 Data … Section n Data Section-Header Table Linkable File Executable File ELF Header e_ident [ EI_NIDENT ] e_type e_machine e_shoff e_version e_flags e_entry e_phoff e_ehsize e_phentsize e_phnum e_shentsize e_shnum e_shstrndx Section-Header Table: e_shoff, e_shentsize, e_shnum, e_shstrndx Program-Header Table: e_phoff, e_phentsize, e_phnum, e_entry Section-Headers sh_name sh_type sh_flags sh_addr sh_offset sh_size sh_link sh_info sh_addralign sh_entsize Program-Headers p_type p_offset p_vaddr p_paddr p_filesz p_memsz p_flags p_align Memory: Physical vs. Virtual Portions of physical memory are “mapped” by the CPU into regions of each task’s ‘virtual’ address-space Virtual Address Space (4 GB) Physical address space (1 GB) Linux ‘Executable’ ELF files • The Executable ELF files produced by the Linux linker are configured for execution in a private ‘virtual’ address space, whereby every program gets loaded at the identical virtual memory-address (i.e., 0x08048000) • We will soon study the Pentium’s paging mechanism which makes this possible (i.e., after we have finished Project #2) Linux ‘Linkable’ ELF files • But it is possible that some ‘linkable’ ELF files are self-contained (i.e., they do not need to be linked with other object-files or libraries) • Our ‘manydots.o’ is such an example • So we can write our own system-code that can execute the instructions contained in a stand-alone ‘linkable’ object-module, using the CPU’s ‘segmented’ physical memory Our ‘loadmap.cpp’ utility • We created a tool that ‘parses’ a linkable ELF file, to identify each section’s length, type, and location within the object-module • For those sections containing the ‘text’ and ‘data’ for the program, we build segmentdescriptors, based on where the linkable image-file will reside in physical memory 32-bit versus 16-bit code • The Linux compilers, and ‘as’ assembler, produce object-files that are intended to reside in ’32-bit’ memory-segments (i.e., the ‘default’ bit in the segment-descriptor is set to 1) • This affects the CPU’s interpretation of the machine-instructions that it fetches • Our ‘as86’ assembler can produce either 16-bit or 32-bit code (though its default is 16-bit code) • We can employ ‘USE32’ or ‘USE16’ directives Example: ‘as86’ Listing 0x0000 01 D8 0x0002 66 01 D8 0x0005 90 USE32 add eax, ebx add ax, bx nop 0x0006 66 01 D8 0x0009 01 D8 0x000B 90 USE16 add eax, ebx add ax, bx nop END Demo-program • We created a Linux program (‘hello.s’) that invokes two system-calls (‘write’ and ‘exit’) • We assembled it with the ‘as’ assembler: $ as hello.o –o hello.o • The linkable ELF object-file ‘hello.o’ is then written to our boot-disk (track 0, sector 14) using: $ dd if=hello.o of=/dev/fd0 seek=13 • (It will get loaded into memory by ‘trackldr’) Memory-Map Loaded from Track 0 of boot-disk by ‘trackldr.b’ ‘trackldr.b’ read from Track 0 of boot-disk by ROM-BIOS bootstrap ‘hello.o’ image 0x00011800 ‘try32bit.b’ image 0x00010000 BOOT-LOADER 0x00007C00 ROM-BIOS DATA IVT 0x00000400 Segment Descriptors • We created 32-bit segment-descriptors for the ‘text’ and ‘data’ sections of ‘hello.o’ (in a Local Descriptor Table) with DPL=3) • For the ‘.text’ section: offset in ELF file = 0x34 size = 0x23 • So its segment-descriptor is: .WORD 0x0023, 0x1834, 0xFA01, 0x0040 (base-address = load-address + file-offset) Descriptors (continued) • For the ‘.data’ section: offset in ELF file = 0x58 size = 0x0D • So its segment-descriptor is: .WORD 0x000D, 0x1858, 0xFA01, 0x0040 (base-address = load-address + file-offset) • For the ring3 stack (not part of ELF file): .WORD 0x0FFF, 0x2100, 0xF201, 0x0040 Task-State Segment • Because the system-calls (via int 0x80) will cause privilege-level transitions, we will need to setup a Task-State Segment (to store the ring0 stacktop pointer) theTSS: .WORD 0, 0, 0 ; 3 longwords • Its segment-descriptor goes into our GDT: .WORD 0x000B, theTSS, 0x8901, 0x0000 Transition to Ring 3 • Recall that we use ‘retf’ to enter ring 3: push word #userSS push word #0x1000 push word #userCS push word #0x0000 retf System-Call Dispatcher • All system-calls are ‘vectored’ through IDT interrupt-gate 0x80 • For ‘hello.o’ we only require implementing two system-calls: ‘exit’ and ‘write’ • But to simplify future enhancements, we used a ‘jump-table’ anyway (for now it has a few ‘dummy’ entries that we can modify later) System-Call ID-numbers • System-call ID #0 (it will never be needed) • System-call ID #1 is for ‘exit’ (required) • System-call ID #2 is for ‘fork’ (deferred) • System-call ID #3 is for ‘read’ (deferred) • System-call ID #4 is for ‘write’ (required) • System-call ID #5 is for ‘open’ (deferred) • System-call ID #6 is for ‘close’ (deferred) (NOTE: over 200 system-calls exist in Linux) Defining our jump-table sys_call_table: .LONG do_nothing ; for service 0 .LONG do_exit ; for service 1 .LONG do_nothing ; for service 2 .LONG do_nothing ; for service 3 .LONG do_write ; for service 4 NR_SYS_CALLS EQU ( *- sys_call_table)/4 Setting up Interrupt-Gate 0x80 • The Descriptor Privilege Level must be 3 mov edi, #0x80 ; gate ID-number lea di, theIDT[edi*8] ; descriptor addr mov 0[di], #isrSVC ; entry-pt loword mov 2[di], #sel_CS ; USE32 code mov 4[di], #0xEE00 ; DPL=3 intr-gate mov 6[di], #0x0000 ; entry-pt hiword Using our jump-table isrSVC: idok: ; service-number is found in EAX cmp eax, #NR_SYS_CALLS jb idok xor eax, eax CSEG jmp dword sys_call_table[eax*4] Our ‘exit’ service • When the application invokes the ‘exit’ system-call, our mini ‘operating system’ leaves protected-mode and returns back to our ‘trackldr’ boot-loader program • (The ‘exit-code’ is simply discarded, since this isn’t a multitasking operating-system) Our ‘write’ service • We only implement writing to the STDOUT device (i.e., the video display terminal) • For most characters in the user’s buffer, we just write the ascii-code (and standard display-attribute) directly to video memory at the current cursor-location and advance the cursor (scrolling the screen if needed) • Special ascii control-codes (‘\n’, \’r’, \’b’) are treated differently, as on a TTY device In-Class Exercise • The ‘manydots.s’ demo (to be used with Project #2) uses the ‘read’ system-call (in addition to ‘write’ and ‘exit’) • However, you could still ‘execute’ it using the ‘try32bit.s’ mini operating-stem, letting the ‘read’ service simply “do nothing” (or return with “hard-coded” buffer-contents) • Just modify the LDT descriptors so they conform to the sections in ‘manydots.o’