A Genealogy of the Woman Student: from Robbins to the present day [PPTX 16.53MB]

advertisement

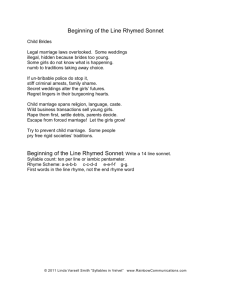

![A Genealogy of the Woman Student: from Robbins to the present day [PPTX 16.53MB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015030208_1-7c6536f929a64aaf41244fccf5810133-768x994.png)

A Genealogy of the Woman Student: From Robbins to the Present Day Robbins Report 50 Years On: Feminist Responses University of Sussex 2 December 2013 Professor Carole Leathwood Institute for Policy Studies in Education (IPSE) London Metropolitan University The woman student - then and now 1963 2013 • 31 universities • In 1962-3, women were 25% of students in British universities • Just 10% at Cambridge, 15% at Oxford • 129 HEFCE funded • In 2012-13, women were 55.2% of accepted applicants • In 2011-12, women were 46.8% at Cambridge and 50.5% at Oxford • In 2013, women constituted 72% of English A level entrants, compared to 21% of physics entrants • In 1960-61, 66% of women with 2 A level passes took arts only and 26% took science only. Genealogy • A ‘history of the present’ • Focus on specific localised events in context • Emphasises discontinuities, interruptions, recurrences rather than continuous linear development or progress • Concerned with ‘subjugated knowledges’ ‘subjugated knowledges [...] were concerned with a historical knowledge of struggles’ ‘Let us use the term genealogy to the union of erudite knowledges and local memories which allows us to establish a historical knowledge of the struggles and to make use of this knowledge tactically today’ (Foucault 1976 in Gordon 1980, p. 83) ‘The feminist project of recovering women’s presence in history seems to be in line with the genealogical interest in peripheral histories and subjugated knowledges’ (Tamboukou 2003, p. 35) The Robbins Committee Report 1963 Aims of HE • ‘instruction in skills suitable to play a part in the general division of labour’ • ‘what is taught should be taught in such a way as to promote the general powers of the mind. The aim should be to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women’ • ‘The advancement of learning […[ the search for truth [...] the advancement of knowledge’ • ‘the transmission of a common culture and common standards of citizenship’ Women in the Robbins Report • Separate heading ‘Women in higher education’ • Untapped talent – including amongst women • Changes in professional requirements for the occupations ‘open to girls’ may mean in future they need to do HE courses. • New curricula developments in HE, eg language courses, ‘may prove particularly attractive to girls’ • The importance of updating or refresher courses for married women – along with ‘adequate financial arrangements’ Married women ‘..a new career pattern has emerged: a short period of work before marriage, and a second period of work starting perhaps fifteen years later, and continuing for twenty years or more ... The prospect of early marriage leads girls capable of work in the professions to leave school before they have entered the sixth form and, even after sixth form studies, too many girls go straight into employment instead of into higher education. When their family responsibilities have lessened many of them will desire opportunities for higher education. And many if not most married women who have already enjoyed higher education will need refresher courses before they can return effectively to professional employment. This will be particularly true for doctors, for teachers and for social workers, but there will also be a need in other fields such as commerce and languages. There is here a considerable reserve of unused ability, which must be mobilised if the critical shortages in many professions are to be met.’ (Robbins 1963, p. 167) Academic staff in Robbins ‘ ‘The young scientist needs time to press ahead with his research when his imagination is at its liveliest; his colleague in the arts may be better occupied in wide reading than in research on particular problems and he may well need more time free from teaching when his crop is ready for harvesting in middle life.’ (ibid. p 184) ‘The fact that the colleges own many houses in the near neighbourhood makes it possible for a non-resident tutor to dine in college and be available outside ‘office hours’ without feeling he is neglecting his wife and family, and he can entertain his students without imposing undue burdens on his wife.’ (ibid. p 193) The decade of the degree The sixties in Britain were the decade of the degree; at the end of it there were twice as many students as at the beginning. In the last ten years, whether in industry, in administration or even in the city and the army, the BA or MA has become the password to promotion, and a main instrument of social change the most important rung in the ladder of selfimprovement. (Sampson 1971, p. 155) The woman student at the time of Robbins • Women as reproductive heterosexual bodies: – Women defined by marriage and ‘the early marriage problem’ (Dyhouse 2006) – Women as (hetero)sexualised ‘The ‘early marriage problem’ ‘Marriage for women today is a hazard, as far as university education is concerned ... almost in the category of war service' (Ollerenshaw 1961, cited by Dyhouse 2006) ‘It's much better to be married than to want to be and stay single until after you have got a degree ... That waiting is a tremendous strain. Why wait when you are 22 and you know that so many other girls of your age are married?’ (Bourne 1963) ‘.. extraordinarily well. Marriage seems to settle them. It's the love-life when they are single that is so devastating'. ‘ I think it helped her. Otherwise she would have been wondering whether there was a young man coming along. And to have a home can be a very cheerful thing when you're harassed by work'. (ibid.) Women’s dangerous sexuality 'Not only did the Oxford regime induce hypocrisy and fear, it was also manifestly unfair. The penalties we faced in the women's colleges were much more severe than those governing male sexuality...’ (Rowbotham 2000, cited by Dyhouse 2006) ‘Undergrad morals’? ‘I wanted to be a popular person around the school I got used to blue jokes, I wasn't exactly displeased after a while when people made personal remarks about my figure. This seemed to make me universally considered fair game. I was constantly bombarded with invitations to go to bed.’ (The Beaver 1964) The University of Sussex ‘Sussex soon enjoyed special publicity as a kind of glamorous Brighton finishing school full of pretty girls and avant-garde intellectuals’ (Sampson 1971, p. 165) ‘Sussex University has proved so attractive to women that there has to be discriminatory selection in the arts subjects to prevent the student population from becoming predominantly female. In consequence, the academic ability of women students at Sussex is said to be on average above that of men.’ (Ollerenshaw 1967, p. 67) Women students: sexualised desirable bodies... Now ‘Frilly Feminists’ in Mail Online – women students fighting for the right to be in ‘beauty contests’, 2008 Reflections on a genealogy 'Within the spaces of these contested sites, ridden by contradictions and uncertainties, the technologies women used to map their existence would be a nexus of resistance and accommodation practices, inextricably interwoven' .. and through these technologies of resistance 'women began to fashion new forms of subjectivity‘ (Tamboukou 2003, p. 4) References • • • • • • • • Blackburn, R. M. and J. Jarman (1993). Changing Inequalities in Access to British Universities. Oxford Review of Education 19(2): 197-216. Bourne, R. (1963) 'Students' union' , The Guardian, 3 October. Dyhouse, C. (2006) Students: A Gendered History. London: Routledge Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977, C. Gordon (Ed.). New York and London, Harvester Wheatsheaf. Foucault, M. (1988). Politics, Philosophy, Culture: Interviews and Other Writings, 1977-1984 London, Routledge. Ollerenshaw, K. (1967) The girls' schools: The future of the public and other independent schools for girls in the context of state education. London, Faber and Faber. Sampson, A. (1971) The New Anatomy of Britain, London, Hodder and Stoughton Tamboukou, M. (2003). Women, Education and the Self: A Foucauldian Perspective. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan