Posttraumatic Growth as Experienced by Childhood Cancer Survivors and Their Families

advertisement

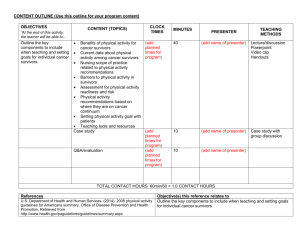

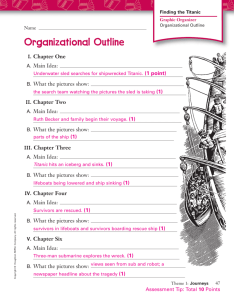

Posttraumatic Growth as Experienced by Childhood Cancer Survivors and Their Families Beyhan Duran, RN, MS, OCN PhD Candidate, UConn SON, Medical Oncology Nurse Yale Cancer Center Sept 3, 2013 Declaration of Conflicting Interest I declared no potential conflicts of interest or no financial support for this research. Acknowledgement Special thanks to the DeVita family for the permission to use their family photos in this presentation Structure of My Presentation • Present a brief background on childhood cancer • Talk about theoretical perspectives on growth • Explain the methodological steps of doing a narrative synthesis • Summarize the results of the positive effects of cancer as perceived by childhood cancer survivors and their families Posttraumatic Growth as Experienced by Childhood Cancer Survivors and Their Families Duran, B. (2013). Posttraumatic growth as experienced by childhood cancer survivors and their families: a narrative synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs, 30(4), 179-197. Background • Before the 1980s, children w/ cancer were almost certain to die of their illness. • The median survival time for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common cancer in children, was only 3 to 6 months after diagnosis. • The bulk of the literature before the 1980s covered topics on death and dying. (Brad & Copeland, 1987; Grootenhuis & Last, 1997). Advances in Pediatric Oncology • In 2000, the four major childhood cancer research groups merged to become the largest randomized clinical trial group w/ a new unified name, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) in the US (Armstrong & Reaman, 2005). Advances in Pediatric Oncology • As a result, there was a stunning progress in both the treatment of childhood cancer, and psychological studies • Childhood cancer has been reclassified as a chronic, life-threatening but curable illness. • The five-year cancer free survival rate is now 80%. • The 10-year survival rate is almost 75%. (ACS, 2013: Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2012-2013; Armstrong & Reaman, 2005, J Ped Psychol, 30(1), 89-97; Oeffinger et al., N Engl J Med, 2006; 355(15), 1572–82) Context of this presentation • Illness-related crises challenge people’s worldviews and values. • Struggling with these challenges, some people not only recover from their illnesses, but also surpass their previous psychological and social functionality. • They reach their full potentials or capacities. Take Home Messages Dealing with a life-threatening illness may serve as an opportunity for: • positive psychological changes, • self-renewal, • spiritual and personal growth, • achieving higher level of functioning (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006; Jaffe, 1985; James & Samuels, 1999; Jim & Jacobsen, 2008; Tu, 2006). Posttraumatic Growth • Posttraumatic growth is a positive psychological change that comes after struggling with highly challenging life crises (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004) Signs of Posttraumatic Growth • greater appreciation of life and changed sense of priorities • warmer, more intimate relationships with others • a greater sense of strength • recognition of new possibilities or paths for one’s life • spiritual development (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004) The Review Systematic Narrative Synthesis Duran, B. (2013). Posttraumatic growth as experienced by childhood cancer survivors and their families: a narrative synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs, 30(4), 179-197. Research Design • Research design was narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. • The guidance for this narrative synthesis was recently formulated and developed by the British health research scholars (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009; Popay et al. 2006, Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews) Narrative Synthesis • It is an approach to synthesize findings from multiple studies, • it relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarize and explain the findings of synthesis. (Popay et al., 2006) Aim • It examines existing literature on the positive effects of cancer and/or the perception of benefit finding among childhood cancer survivors and their families. Inclusion Criteria Inclusion Criteria • Written in English • Has clearly described methods • Focuses on childhood cancer survivors • Focuses on the positive effects of cancer • Reports at least one positive growth outcome • No date restrictions applied because of the limited number of studies available Sample • N=35 primary studies (1975 – 2010) – 30 published – 5 doctoral dissertations • Sample Design – Quantitative, N=20 – Qualitative, N=12 – Mixed studies, N=3 Sample-Participants • • • • • • Childhood cancer survivors, N= 2087 Parents, N= 1115 Mothers, N= 689 Fathers, N= 341 Listed only as “parents” = 85 Healthy siblings, N=159 Table 1 illustrates the country of origin of these papers (N=35) Country Published Papers Canada 3 Finland 2 Hawaii 1 Ireland 1 Italy 1 Sweden 1 The Netherlands 1 UK 2 USA 23 Data Analysis • Preliminary Data Analysis – Textual descriptions of studies – Groupings and clusters – Tabulation – Transforming quantitative data into a common themes/categories – Translating data; thematic synthesis Table 2. Example of Methodological Characteristics of the Qualitative Individual Studies Included in This Review (N = 15). Studies Discipline (Norberg & Green, 2007) Women & Child Health (Prouty et al., 2006) Nursing (Parry & Chesler, 2005) Social Work & Sociology Country Research Design Data Collection/Data Analysis Qualitative Audio-taped interview; Thematic analysis USA Qualitative Audio-taped interview; Phenomenologic al study USA Qualitative Constant comparison and analytic induction In-depth Qualitative interviews Sweden Table 3. Example of Demographic Characteristics of the Qualitative Individual Studies Included in This Review (N = 15). Author (Year) Participants Ages of Survivors At diagnosis Cancer Survivors’ Diagnosis Time Elapsed Major Since Results Treatment Ended (Michel et al., 40 Mothers, 6 2010) fathers, 41 adolescent survivors (22 girls, 19 boys) 12-15 y/o Mean age at dx was 5 yrs Leukemia, CNS or solid tumor 6.6 years Leukemia survivors reported more benefit-finding than solid tumor survivors did. (Fritz, 2005) Current age 18- Leukemia 27 yrs. Age at Dx 7- 16 yrs. Off treatment for more than 5 years Many mothers reported experiencing personal growth, personal strength, a new attitude, and a newfound voice 12 mothers, 3 fathers, 17 Survivors (10 female, 7 male) Figure illustrates the line-by-line coding using screenshots of Atlas.ti. Qualitative Studies Quantitative Studies Figure 1. Review Process (Adapted from Harden et al., 2004; Harden & Thomas, 2005; Popay et al., 2006; Pope et al., 2007). This is how I felt after data analysis! Positive Effects of Childhood Cancer RESULTS Five core themes were identified: 1. Making sense of cancer experience 2. Appreciation of life 3. Greater self-knowledge 4. Positive attitudes toward family 5. A desire to pay back society Meaning-Making It is not what happens to you, but the way you take it -Hans Selye Meaning-making refers to • “[the process of survivors] coming to see the situation in a different way and reviewing one’s beliefs and goals in order to regain consistency among them” (Park & Ai, 2006, p. 393). • In other words, we try to understand our appraised meaning of an event when our believe system is disrupted or violated (Park & Folkman, 1997). Parental Reactions to the Bad News • Several mothers reported that they were puzzled after hearing their child’s diagnosis. • “How could this be possible? This isn’t supposed to happen to us?” • “[W]hy does God let anything like this happen?” (Cohen, 1994, p. 130; McCubbin, at al., 2002, p. 105). Making sense of cancer experience Positive meaning-making outcomes: Religious meaning-making Meaning-making through being “Special” Meaning-making through benefit-finding Randomness of events There is no answer Religious Meaning-Making • This newfound meaning was expressed in explicitly religious terms by some parents and in philosophical terms by others (Slavin, 1981). • The families who found religious meaning in their misfortune believed that God had a plan as to why the cancer survivors lived, whereas others died. ( Britt, 1992; Chesler & Barbarin, 1987; Cohen, 1994; Gogan & Slavin, 1981). Religious Meaning-Making One of the survivors reported: “[My mother] always said, ‘There is a reason why you lived. God has plans for you. You are going to do great things. You are going to do something’” (Cohen, 1994, p. 147). Religious Meaning-Making • When families exhaust all possible means to make sense of their life-threatening event, religious beliefs become a psychological antidote to foster hope and meaning of illness. Religious Meaning-Making • Religious beliefs may positively influence the grieving process by providing believers with ready-made interpretations or frames of reference with meaning and explanation for otherwise meaningless phenomena. (Gray, 1987; Pargament & Park, 1995; Spiro, 1966) Meaning-Making through Benefit-Finding “I’m no longer angry at why she got it, at all. And I don’t ask, ‘Why us?’ anymore, because there have been too many positives out of it; to a newly diagnosed family, you could never say that, but there was good” (Mother, Britt, 1992, p. 72). Meaning-making through being “Special” • Some cancer survivors believed that they survived because they were “special.” • They felt that a “life force” controlled their life and spared them from death. (Fritz, 2005; O'Malley, 1981; Parry, 2003) Unable to Find Meaning • Some families reported that they were unable to find any answers for their child’s misfortune. • They finally resolved this question to their satisfaction by accepting that no answer can be found. (Chesler & Barbarin, 1987; Foster, O'Malley, & Koocher, 1981) Randomness of the Event • The belief that a child’s cancer was a random event was held by 72% of cancer survivors, 62% of mothers, and some siblings. (Fritz, 2005; Kazak, Stuber, Barakat, & Meeske, 1996) Appreciation of life You cannot understand “being” (life) until you experience and fully comprehend “nonbeing” or “nothingness” (death). (Sartre, 1943/1984, Being and Nothingness) Appreciation of life • Individuals faced with trauma tend to experience an increased sense of vulnerability. • This existential reevaluation of one’s life made the majority of young cancer survivors realize that life is fragile and hence very precious. (Janoff-Bulman, 1992, 2004) Life is Precious “I have a whole new outlook on life. After what I’ve been through, I realized how precious life is, instead of taking it for granted. It’s just too short” (Karian, Jankowski, & Beal, 1998, p. 157) Acquired New Philosophy of Life Life philosophy refers to the sum of a person’s attitudes, beliefs, and values about how the world functions, including social cognitions about oneself, as well as one’s social and objective environment (Inglehart, Reactions to critical life events, 1991, p. 171). Acquired New Philosophy of Life • Nine cancer survivors and three parents in eight studies reported that they developed a greater sense of appreciation of the time they had, the here and now. • They all believed that one should live life consciously and to the fullest while being here in the present moment ( Chesler, Weigers, & Lawther, 1992; Cohen, 1994; Gray, et al., 1992; Kaffenberger, 1999; Karian, et al., 1998; Parry, 2003; Parry & Chesler, 2005; Van Dongen-Melman, et al., 1998). New values and life priorities “Having cancer has really shown me what is important in life -- how all the petty things I used to worry about really mean nothing” (Adolescent Sarcoma Survivor, Novakovic, et al., 1996, p. 58) Greater self-knowledge The most commonly reported statements by young survivors were: • “My self-esteem has improved,” (Cohen, 1994, p. 76) • “I’m a better person because of the cancer” (Karian, et al., 1998, p. 158). • “I do believe that we are the sum of our experiences. I am now who I am because of what happened to me” (Cohen, 1994, p. 87). Grow Up Faster • One of the most common comments made by survivors was that they felt they grew up faster and became more mature than their peers as a result of dealing with cancer. (Chesler, et al., 1992; Cohen, 1994; Fritz & Williams, 1988; Holmes & Holmes, 1975; Kaffenberger, 1999; Karian, et al., 1998; Parry & Chesler, 2005; Wasserman, Thompson, Wilimas, & Fairclough, 1987). Grow Up Faster “You have to grow up so fast. One minute you’re a little kid, playing with your friends and Barbies, and the next minute you’re in the hospital with people you don’t know, and kids are dying around you every day” (Survivor, Parry & Chesler, 2005, p. 1062). Family Closeness and Togetherness The majority of families and the survivors reported that • their experience with their/child’s illness had a positive effect on family life, • they place greater value on relationships, • they have more satisfaction and improvement in family relationships, • less personal stress associated with medical situations (Britt, 1992; Chesler & Barbarin, 1987; Cohen, 1994; Fritz, 2005; Kaffenberger, 1999; Karian, et al., 1998; McCubbin, et al., 2002; Quin, 2004). A desire to pay back society The most fulfilling kind of life is one lived in service to others – Mahatma Gandhi Many survivors reported that • they served as peer counselors. • talked to newly diagnosed children and their families. • supporting other families was very meaningful to them • they became sensitive toward others in similar situations. (Kaffenberger, 1999; Karian, et al., 1998). Importance of the Knowledge to be Gained • This narrative synthesis aims to educate nurses, social workers, oncologists, and researchers about the positive outcomes of childhood cancer. • The information presented here can facilitate interventions – to enhance the quality of life, – to aid rehabilitation efforts, and – to guide the health promotion behavior of parents who have children with cancer. In Conclusion • The challenges of cancer “holds up a great mirror to [survivors] and let them look at [themselves] in their infinitive variety. This… is the meaning of [cancer’s] work in [previously naïve, unchallenged cancer victims].” (Clyde Kluckhohn, 1949, p. 11, Mirror For Man: The relation of Anthropology to modern Life). Thank you For your Time! For any questions: beyhan.duran@yale.edu