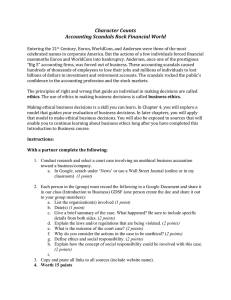

Sarbanes-Oxley Act Aims to Restore Trust Among Investors

advertisement

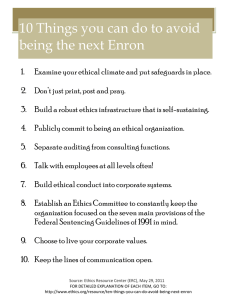

Sarbanes-Oxley Act Aims to Restore Trust Among Investors Rafael Gerena-Morales. Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. Washington: Aug 3, 2003. pg. 1 Abstract (Document Summary) Now, as Sarbanes-Oxley passes its one-year anniversary, companies large and small are making changes to comply with its provisions. In South Florida, for example, BankAtlantic Bancorp of Fort Lauderdale has enhanced its internal audit committee by adding two independent members with financial experience. And AutoNation of Fort Lauderdale has adopted a separate code of business ethics for its directors and senior officers. [Sarbanes-Oxley]'s independence provision makes audit committees more apt to challenge financial figures and could restore public trust, says David Hardesty, an accountant from Larkspur, Calif., and author of a book titled Corporate Governance and Accounting Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. "The public lost trust in accounting." The lack of proper controls gave executives and accountants broad leeway on many accounting and governance issues. At Tyco, weak internal controls were cited, among many other failures, as having allowed for flawed lending practices in which more than $3 million in employee relocation loans were issued even though the loans did not meet Tyco's own guidelines. At WorldCom, weak internal controls were cited as helping the company's then CEO, Bernard Ebbers, obtain more than $1 billion in company loans. Full Text (2450 words) Copyright 2003, South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Distributed by KnightRidder/Tribune Business News. To see more of the South Florida Sun-Sentinel -- including its homes, jobs, cars and other classified listings -- or to subscribe to the newspaper, go to http://www.sun-sentinel.com. Aug. 3--The accounting scandals of the past two years undermined the most valuable commodity in the U.S. stock market: trust. For many investors, the accounting fraud at companies such as Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco broke their belief in a system in which corporate leaders are supposed to honestly boost shareholder value, auditors are supposed to ensure the accuracy of financial reports, and boards of directors are supposed to make sure everyone is doing their jobs. But the accounting scandals showed this chain of oversight broke under the pressure of falling stock prices after 2001, and that many companies flat-out lied about sales and earnings. Thus, the numbers reported in financial reports and mutual fund statements delivered to millions of homes were largely a mirage for investors, who collectively lost billions of dollars after the accounting frauds came to light. In response to the historic lapse, President Bush signed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act into law to toughen accounting and governance standards at the nation's public companies. The law's chief goal is to restore trust among millions of investors. Now, as Sarbanes-Oxley passes its one-year anniversary, companies large and small are making changes to comply with its provisions. In South Florida, for example, BankAtlantic Bancorp of Fort Lauderdale has enhanced its internal audit committee by adding two independent members with financial experience. And AutoNation of Fort Lauderdale has adopted a separate code of business ethics for its directors and senior officers. But a nagging question remains: Will Sarbanes-Oxley make a difference? Here are four ways in which Sarbanes-Oxley is changing how public companies do business -- why each is important -- and why each will or won't matter. Accounting firms had been perceived as getting too cozy with management at the companies they audited because of their pursuit of lucrative consulting business. This is largely believed to have weakened the rigor of audits and undermined the accuracy of financial data that investors rely on. Former Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Arthur Levitt Jr. noted that the growing portion of revenues from consulting at the major accounting firms was a concern. In a 1996 speech, Levitt warned, "I caution the industry, if I may borrow a biblical phrase, not to 'gain the whole world, and lose [its] own soul.'" The then Big Five accounting firms rejected Levitt's warnings. Now, under Sarbanes-Oxley, a provision that takes full effect in May 2004 forbids accounting firms from simultaneously providing auditing and consulting services, except for tax consulting. Some South Florida firms are already acting on the rule. Office Depot has decided not to use its auditors, Deloitte & Touche, on any management consulting. Office Depot last year spent nearly $2 million on tax-related services and $6.2 million on consulting, the company says. At AutoNation, KPMG now serves as the company's auditor, replacing Deloitte & Touche, which will continue providing consulting services. "When outside auditors offer a company consulting services as well ... the relationship is not healthy," says Paul Hodgson, senior research associate at The Corporate Library, a corporate governance watchdog group in Portland, Maine. The provision that severs the relationship "moves things in the right direction." Audit committees are responsible for overseeing the work of outside auditors, which should make these committees a crucial safeguard for accounting accuracy. While the audit committee members at many public companies were independent, some were not. Before Sarbanes-Oxley, it had been possible for the audit committee to include members of a company's management team, or suppliers, vendors or customers. Critics say this system made some non-independent audit committee members beholden to management, and less likely to challenge dubious accounting practices. An example of such a conflict of interest emerged at WorldCom, where Max E. Bobbitt, chairman of the company's audit committee, was allowed a $1-a-month lease on a WorldCom corporate jet. Sarbanes-Oxley forbids such relationships and requires that all audit committee members be independent. That means they can only accept a director's fee; also, they can't accept loans or consulting fees from the company or do business with it. Under Sarbanes-Oxley, audit committees now have the exclusive power to hire and fire outside auditors. Before the law, corporate managers, such as CEOs, could hire and fire outside auditors. In South Florida, Carnival Corp., the Miami-based cruise line, and FPL Group, the Juno Beach-based utility company, have each expanded their audit committees by adding another independent member. Sarbanes-Oxley's independence provision makes audit committees more apt to challenge financial figures and could restore public trust, says David Hardesty, an accountant from Larkspur, Calif., and author of a book titled Corporate Governance and Accounting Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. "The public lost trust in accounting." Poor internal accounting controls have been faulted for having allowed corporate leaders to influence outside accounting firms into accepting and endorsing manipulated earnings figures. Weak audit committees and boards of directors that didn't probe deeply enough also failed. In accounting, there are many gray areas open to interpretation - - such as when to recognize revenue -- that rely on judgment calls. At many public companies, faulty internal controls did not offer a protocol for, say, how to issue employee loans or how to resolve disputes between management and auditors regarding financial reports. The lack of proper controls gave executives and accountants broad leeway on many accounting and governance issues. At Tyco, weak internal controls were cited, among many other failures, as having allowed for flawed lending practices in which more than $3 million in employee relocation loans were issued even though the loans did not meet Tyco's own guidelines. At WorldCom, weak internal controls were cited as helping the company's then CEO, Bernard Ebbers, obtain more than $1 billion in company loans. Sarbanes-Oxley includes a provision, section 404, that requires public companies to assess the strength of their internal controls, identify weaknesses, and document their systems in detail. For companies with stock market values of $75 million or higher, the law applies for fiscal years ending on June 30, 2004, or later. It applies to smaller companies for fiscal years ending on April 2005 or later. In South Florida, companies are already employing a range of strategies to tighten internal controls and improve the accuracy of financial data. Watsco of Coconut Grove has set up an employee hotline where workers can voice concerns about internal controls, and Spherion of Fort Lauderdale has plans for a similar hotline. World Fuel Services of Miami has created internal committees that must sign off on the accuracy of financial statements before they are passed on to the company's CEO and chief financial officer for their signatures. "We want to make sure our people are making the same attestations to us," says Francis X. Shea, World Fuel's CFO. Forcing public companies to evaluate and document internal controls is "an enormous job," says Christian Bartholomew, a former SEC attorney who litigated fraud. He is now a partner at the law firm, Morgan Lewis, based in its Miami office. "It creates a lot of paperwork." But, he adds, "Anything that forces companies to take a hard look at their financial controls is a positive measure. You can't cook the books without circumventing internal controls." Of course, none of the accounting scandals would have occurred without seismic ethical lapses among corporate leaders, accountants and boards of directors. Under the pressures of falling earnings and stock prices and the burden of meeting Wall Street expectations, a full roster of business characters throughout Corporate America simply did wrong instead of right. Pick any major accounting scandal in 2001 or 2002. Ethical collapses dogged them all: Enron, WorldCom, Tyco. On Thursday, the U.S. General Services Administration suspended federal business with WorldCom, valued at more than $1 billion annually, because WorldCom lacked sufficient "internal controls and business ethics." Sarbanes-Oxley attempts to get public companies to enhance ethics standards by forcing them to adopt a code of ethics or explain why they don't have one. In response, public companies are forming new codes or updating existing policies. In South Florida, Watsco is drafting a new 10-page code of ethics that includes changes to an insider trading policy that previously applied only to a few executive officers. Now key managers will also be affected by the expanded policy. At Citrix Systems, the company recently added Web-based training modules on ethics, and its code of conduct, that each take 45 minutes to review. Citrix employees are expected to complete both training modules by year's end, the company says. While many corporate governance experts say there is symbolic importance in persuading companies to adopt a code of ethics, many say this Sarbanes-Oxley provision is among the weakest because it can't dissuade a person determined to commit corporate fraud. "Having a code of ethics helps, but it's not as effective a provision as forcing companies to have independent auditors," says Jonathan Awner, chairman of the corporate practice group at the Miami office of Akerman Senterfitt, a law firm. Just because a company hangs a "code of ethics on the wall," that won't stop someone bent on breaking the law, he says. Business Writers Purva Patel, Joseph Mann, Karen-Janine Cohen, Doreen Hemlock, Christine Winter, Joan Fleischer Tamen, Christian Moises, Marcia Heroux Pounds, and Jenni Bergal contributed to this report. SUMMARY: Summary of activities leading up the the signing into law of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 2001 Enron hides billions in debt to appear profitable. Execs sell more than $1 billion in Enron stock as their schemes unravel, while they encourage workers to invest in the energy giant. August 15: Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling resigns. December 2: Enron files Chapter 11 bankruptcy. December 12: Congress launches investigation into Enron accounting practices and individuals' culpability. 2002 January 28: Global Crossing files Chapter 11 bankruptcy, the fourth largest in history. Gary Winnick, the founder and chairman, sold $734 million of stock between 1998 and January. March 14: Arthur Andersen indicted on a single count of obstruction of justice for destroying thousands of documents related to the Enron investigation. April 27: WorldCom CEO Bernard Ebbers resigns. April 28: The Securities and Exchange Commission approves a settlement with nine of Wall Street's biggest brokerage firms that will cost them $1.4 billion and make them cut the links between analysts' stock research and the firms' investment-banking business. June 3: Business tycoon Dennis Kozlowski is booked on felony charges of dodging state sales tax on more than $13 million of paintings. He resigned as Tyco CEO as word of the investigation leaked out. He was later charged with fraud, accused of a massive effort to loot tens of millions of dollars from the company. June 15: Arthur Andersen guilty of obstruction of justice for trying to hinder a government investigation of accounting at Enron, whose books Andersen audited. June 25: Adelphia Communications files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection as it tries to overcome more than $20 billion in debt, mounting losses and a scandal over alleged selfdealing by the founding family. June 25: WorldCom documents more than $3.7 billion in expenses after an internal investigation uncovered what appears to be one of the largest cases of accounting fraud ever. WorldCom scandal swells to $9 billion by Nov. 5. July 21: WorldCom files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the largest in history. July 23: The Dow Jones industrial average closes at 7,702, dropping more than 1,500 points in four weeks. July 30: President Bush signs into law the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. RETHINKING POLICIES One year after its passage, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which aims to toughen accounting and governance standards, has companies rethinking, revising and creating new policies, as well as reshaping boards and committees. Here's a sample of what some South Florida firms are doing: AUTONATION: Fort Lauderdale auto retailer --Appointed two new independent directors to its board. --Adopted a separate code of ethics for its directors and officers. --Kept Deloitte & Touche as its consultants, but shifted auditing business to KPMG. BANKATLANTIC BANCORP: Fort Lauderdale financial services firm --Replaced two audit committee members with two members who have deeper financial experience. --Spent about $1 million to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley. CARNIVAL CORP.: Miami cruise line --Revised its code of ethics. --Added one member to its audit committee, which now has four members. Citrix Systems: Fort Lauderdale software developer --Added Web-based training modules on ethics, and its code of conduct, that each take 45 minutes to review. Citrix employees are expected to complete both modules by year's end. --Kept Ernst & Young as auditors, but for other work hired a different Big Four accounting firm, which the company declined to name. FPL GROUP: Juno Beach energy company --Formed a team to help meet audit requirements. --Added one member to its audit committee, which now has six members. --Is revising code of ethics; top 200 managers are required to read and sign the code. --Deloitte & Touche will continue providing auditing services but non-auditing services "will in the future be performed by other firms." LENNAR: Miami home builders --Drafted a new code of ethics. --Adopted an audit committee charter (it did not have one). OFFICE DEPOT: Delray Beach retailer of office supplies --Deloitte & Touche will continue providing auditing services, but not management consulting. --Minor revisions to code of ethics. REPUBLIC SERVICES: Fort Lauderdale waste disposal firm >Hired Ernst & Young as auditors to replace now-defunct Arthur Andersen. >Hired Deloitte & Touche for tax consulting. RYDER SYSTEM: Miami transportation company --The company says it was already in compliance with all of the law's provisions and didn't have to make any changes. SPHERION: Fort Lauderdale staffing and recruitment company >Plans to implement an employee "hotline" for complaints. >In addition to an existing general code of ethics, the company is drafting one specifically for senior financial officers. WACKENHUT CORRECTIONS: Boca Raton prison security firm --Is revising code of ethics. --Formed a disclosure committee to review fraud claims, contract issues and other problems that might arise. WATSCO: Coconut Grove distributor of heating and cooling equipment --Writing its first formal code of ethics, about 10 pages, that will address insider trading policy that previously applied only to a few executive officers. The new code of ethics will also cover key managers. --Established a hotline for employees to call and voice concerns about governance issues. WORLD FUEL SERVICES: Miami seller of marine and aviation fuel --Added more independent members to its board of directors. --Set up committees that must sign off on financial statements before they are sent to the CEO and CFO.