Gwen Murray Fall 2009 Tinker Terminal Report

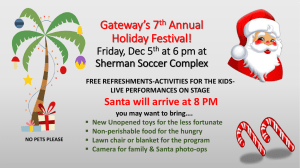

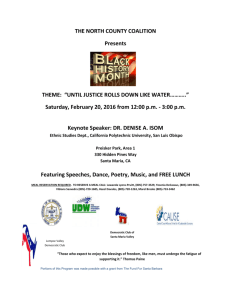

advertisement

Gwen Murray Fall 2009 Tinker Terminal Report (Re)presenting the Periphery: Social Perspective and Brazilian Audiovisual Production Proposal Summary My research in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil sought to answer several questions including: How has the treatment of the urban periphery changed in commercial media, mainly audiovisual fiction? How have joint cultural production initiatives between commercial and community media producers negotiated questions of audience and accountability in the presentation of social issues? Do favela residents recognize a shift in peripheral representation in mainstream audiovisual content? How do commercial producers evaluate their social contribution? Does the academic community perceive these events to be representative of a larger process of social democratization in Brazilian culture? Events in the Field My research started at LASA, where I was able to network with communication professors from the Escola de Comunicação of UFRJ (ECO). Through these contacts, I was able to attend a follow up panel and strategic planning meeting with academics and media professionals who work with community media. Hosted by ECO, the panel featured discussants that spoke on correlations between youth, violence and media reception. Dr. Vicki Mayer was a discussant on this panel reviewing her work with media ethnography and Mexican-American youth. Community media scholar, Raquel Paiva, also invited me to observe a strategic planning session for the Laboratório de Estudos em Comunicação Comunitária da UFRJ (LECC). This research nucleus is devoted solely to understanding the trends, policy and development of community media production and reception. LECC also works in solidarity with local community media actors. These events provided a snapshot of how the local academic community perceives issues of social inequality and its manifestation in media – mainstream and alternative. The principal component of my work in the field was participant observation with social group Atitude Social and their musical education project Aos Pés da Santa Marta. Situated in the Santa Marta favela in Rio de Janeiro, Atitude Social is a 1 community organized and sustained cultural heritage group that works with community members to teach music and dance. I spent two days a week at Santa Marta observing pedagogical methods and documenting program participants and the sociospatial environment at large. Santa Marta is known in Rio as a “favela modelo” meaning that with the recent installation of military police battalions, violent crime has ebbed considerably making the community a prime location for state operated projects in urban beautification and development. One of the most exciting developments – for both residents and local advocates – was the creation of a wireless network in Santa Marta. Of course, simply having access to Internet service does not ensure that residents have access to information. There are related issues in terms of equipment access and usability. After observing community members documenting Aos Pés da Santa Marta with cell phone cameras and video, I began to produce my own multimedia, making short videos, taking pictures (letting some kids use my camera to capture Santa Marta) and also recording rehearsals. The idea was that these media can be used to supplement materials already present on the program’s website to communicate more effectively the scope and nature of their work. The third primary area of research was media gathering. I scoured magazine banks (and the O Globo daily periodical) for any information on the periphery and its presentation. Slowly, as I began to observe the presence of a much larger digital culture in Brazil, my media gathering shifted to issues of digitalization, democratization of access and new media. I was able to gather many articles, a complete multimedia kit from Globo and independent primary sources on web trends and digital culture not only in Rio, but in all of Brazil. Finally, with the assistance of Dr. Mauro Porto, I was able to sit down with Luis Erlanger, director of Globo’s central communications. In our hour and a half long interview we touched on everything from the differences between social merchandising and social content, to Globo-led public service campaigns, to future projects and co-productions between community and mainstream media producers. Summary of Relevant Findings 2 My research produced two actionable data sources. The first was the revelation of the potency of digital media culture in Brazil. While in Santa Marta, the biggest challenge I faced was that community members were very hesitant to talk about social politics. I approached the subject from many angles, but had difficulty gaining entry on such a loaded subject. Initially, I had wanted to conduct a survey on TV viewing habits and social perspective within the miniseries Cidade dos Homens. Although many scenes from the show were filmed in Santa Marta, residents were disinterested. After a couple visits, I realized that digital culture had saturated even Santa Marta. The real story here was not about their reception of the periphery in mainstream media, rather how Santa Marta residents engaged with new media through the documentation of their community. Media production was happening at a very basic level through the use of cell phones. These media served primarily social purposes. The second piece of actionable data is my Luis Erlanger interview. Not only did he send me home with books and multimedia classroom tools from a Globo initiative that addressed racial difference, he clued me in to Globo’s mission to discuss social issues in television fiction and to find new projects and talent outside of their regular talent pool. In accord with other research, these learnings demonstrate further media opening. Future Opportunities for Investigation Though I did not answer all of my research questions, I did come closer to understanding how Globo evaluates their social role and also how joint productions are deepening an understanding of social difference in Brazilian television fiction. Two additional lines of study that stem from this research. The first is Globo’s integrated multimedia campaigns that bridge the world of the TV imaginary to infiltrate the classroom and sites of public opinion formation to drive social change. The second is the digitalization of urban culture and how new technologies are changing notions of access, communication and representation for marginal communities. These technologies are not just development tools, as many scholars have previously theorized; they are in fact important social tools used to entertain and connect with friends and also mainstream popular cultures. 3