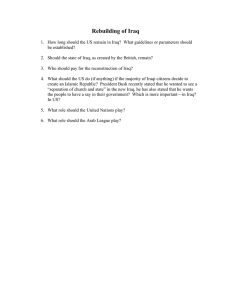

Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security Updated September 6, 2007 Kenneth Katzman

advertisement