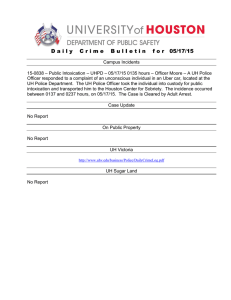

E PREFACE

advertisement