SSR Paper 12

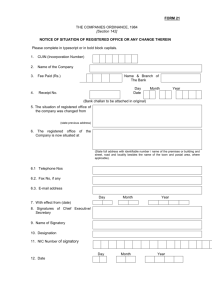

advertisement